FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE:

MARRIAGE AND THE

FEDERAL INCOME TAX

JUNE 1997

The Congress of the United States

Congressional Budget Office

NOTES

Because numbers are often rounded, their sums may not equal totals shown in tables,

figures, and text.

For simplicity of exposition, this paper sometimes uses the term "families" to refer to

both families and individuals.

Values for earnings are sometimes negative. People can have negative earnings if

they lose money in self-employment and the losses exceed incomes from wages or

salaries.

T

Preface

his study examines the ways in which federal tax law affects the income taxes that

married couples pay and how demographic and labor market changes over the last two

decades have altered those effects. It also discusses a variety of possible changes in

the federal tax code that would reduce the higher tax liabilities that married couples often incur

because they cannot file individual tax returns. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO)

prepared the study at the request of Representative Barbara Kennelly of the Committee on

Ways and Means.

Roberton Williams and David Weiner of CBO's Tax Analysis Division wrote the study

under the direction of Rosemary Marcuss and Frank Sammartino. A number of people inside

and outside CBO reviewed drafts and provided valuable criticism and suggestions. They

include Mark Booth, Albert Davis, Theresa Devine, Daniel Feenberg, Diana Furchtgott-Roth,

Amy Rehder Harris, Richard Kasten, Pearl Richardson, and Eugene Steuerle.

Sherwood Kohn edited the manuscript and Marlies Dunson provided editorial assistance.

Simone Thomas produced drafts of the study. Kathryn Quattrone and Jill Sands prepared the

report for publication.

June E. O'Neill

Director

June 1997

Contents

SUMMARY xiii

ONE MARRIAGE PENALTIES AND BONUSES 1

Defining Marriage Penalties and Bonuses

2

A History of the Treatment of Married Couples

in the Federal Income Tax

6

The Significance of Marriage Penalties and Bonuses

9

TWO SOURCES OF MARRIAGE PENALTIES AND BONUSES 15

Factors Giving Rise to Marriage Penalties

and Bonuses

15

Which Couples Pay the Marriage Tax?

25

THREE MAGNITUDES OF MARRIAGE PENALTIES

AND BONUSES 27

Measuring Marriage Penalties and Bonuses

27

Total Marriage Penalties and Bonuses

29

The Distribution of Marriage Penalties

and Bonuses

32

Effective Tax Rates of Married Couples

36

FOUR LABOR MARKET AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGES

AFFECTING MARRIAGE PENALTIES AND BONUSES 37

Working-Age Married Couples

38

Changes in Earnings Among Income Categories

39

Changes in Earnings Among Age Categories

40

Changes in Earnings by Number of Children

42

Overview

44

FIVE REDUCING MARRIAGE PENALTIES 47

Widen Tax Brackets and Raise the Standard

Deduction for Joint Filers

48

Exempt from Taxes Some Income of

Lower-Earning Spouse

51

vi FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE: MARRIAGE AND THE FEDERAL INCOME TAX June 1997

Modify Earned Income Tax Credit to Reflect

Number of Adult Earners

53

Restore the Requirement That Spouses File

Individual Returns

54

Allow Couples Choice of Filing Status

55

Fundamental Tax Reform

56

APPENDIXES

A Tax Treatment of Married Couples in

Other Countries

59

B Treatment of Married Couples Under State

Income Taxes

61

C Characteristics of Married and Unmarried

Couples, 1995

63

D Additional Supporting Tables

69

E Sources of Data

75

F Estimated Marriage Penalties and Bonuses

Under a Divorce Model

77

G The Income Distribution of Families

79

H Comparison of Demographic Changes for Working-Age

Couples and All Married Couples

83

CONTENTS vii

TABLES

S-1. Distribution of Joint Tax Returns and Marriage Penalty

or Bonus as a Percentage of Adjusted Gross Income,

by Adjusted Gross Income of Couple and Penalty or

Bonus Status, Projected 1996 xiv

S-2. Joint Tax Returns by Penalty or Bonus Status and

Division of Earnings Between Spouses, Projected 1996 xv

S-3. Effective Individual Income Tax Rates of Married Couples

Filing Individual or Joint Returns, Projected 1996 xvi

S-4. Alternative Approaches to Reducing Marriage Penalties xviii

1. Effects on Marginal Tax Rates of Married Couples Filing

Jointly Rather than Individually, Projected 1996 12

2. Marriage Penalties and Bonuses for Married and Unmarried

Couples, Simulated 1995 13

3. Factors Determining Whether Couples Face Marriage

Penalties or Bonuses, 1996 16

4. Total Value of and Tax Returns with Marriage Penalties

and Bonuses Under Alternative Measures, Projected 1996 30

5. Couples Receiving Marriage Penalties and Bonuses by

Adjusted Gross Income, Projected 1996 31

6. Marriage Penalties and Bonuses by Adjusted Gross Income

of Couple, Projected 1996 32

7. Joint Tax Returns by Penalty or Bonus Status and Division

of Earnings Between Spouses, Projected 1996 33

8. Marriage Penalties and Bonuses by Penalty or Bonus Status

and Division of Earnings Between Spouses, Projected 1996 34

9. Effective Individual Income Tax Rates of Married Couples

Filing Individual or Joint Returns, by Adjusted Gross

Income and Division of Earnings Between Spouses,

Projected 1996 35

10. Distribution of Working-Age Married Couples, by Division

of Earnings Between Spouses in 1969, 1979, 1989, and 1995 39

11. Percentage of Working-Age Married Couples with Two

Earners, by Total Income in 1969, 1979, 1989, and 1995 40

viii FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE: MARRIAGE AND THE FEDERAL INCOME TAX June 1997

12. Percentage Distribution of Working-Age Married Couples, by

Division of Earnings Between Spouses and Total Income in

1969, 1979, 1989, and 1995 41

13. Percentage of Working-Age Married Couples with Two

Earners, by Age of Older Spouse in 1969, 1979, 1989, and 1995 42

14. Percentage Distribution of Working-Age Married Couples,

by Division of Earnings Between Spouses and Age of Older

Spouse in 1969, 1979, 1989, and 1995 43

15. Percentage of Working-Age Married Couples with Two

Earners, by Number of Children in 1969, 1979, 1989, and 1995 44

16. Percentage Distribution of Working-Age Married Couples,

by Division of Earnings Between Spouses and Number of

Children in 1969, 1979, 1989, and 1995 45

17. Percentage Distribution of Families with Children, by Type

and Number of Earners in Married Couples in 1969, 1979,

1989, and 1995 46

18. Simulated Effects of Demographic Change on Marriage

Penalties and Bonuses, 1969 and 1996 46

C-1. Distribution of Married and Unmarried Couples

by Total Income, 1995 65

C-2. Distribution of Married and Unmarried Couples

by Age of Older Spouse, 1995 66

C-3. Distribution of Married and Unmarried Couples

by Number of Children, 1995 67

C-4. Simulated Marriage Penalties and Bonuses for

Married and Unmarried Couples, 1995 68

D-1. Factors Determining Marriage Penalties and Bonuses

by Adjusted Gross Income, Simulated 1996 70

D-2. Married Couples by Earnings of Each Spouse, Simulated 1996 71

D-3. Married Couples with Marriage Penalties or Bonuses

and Average Penalty or Bonus by Earnings of Each

Spouse, Simulated 1996 72

D-4. Distribution of Marriage Penalties and Bonuses by

Number of Earners, Simulated 1996 74

CONTENTS ix

F-1. Marriage Penalties and Bonuses for Married Couples Under

Alternative Assumptions about Distribution of Children

Between Spouses, Simulated 1996 78

G-1. Percentage Distribution of Families by Income

Category and Family Type, 1995 80

G-2. Distribution of Working-Age Married Couples with

Earnings by Income Category in 1969, 1979, 1989, and 1995 81

H-1. Selection of Married Couples for Analysis Based

on Age and Earnings, 1995 84

H-2. Percentage of Couples with Two Earners: All Married

Couples and Working-Age Married Couples with Positive

Earnings in 1969, 1979, 1989, and 1995 85

H-3. Distribution of Working-Age and All Married Couples

by Division of Earnings Between Spouses in 1969,

1979, 1989, and 1995 86

H-4. Percentage Distribution of Working-Age and All Married

Couples with Two Earners, by Total Income in 1969, 1979,

1989, and 1995 87

H-5. Percentage Distribution of Working-Age and All Married

Couples by Division of Earnings Between Spouses and

Total Earnings in 1969, 1979, 1989, and 1995 88

H-6. Percentage Distribution of Working-Age and All Married

Couples with Two Earners by Age of Older Spouse in 1969,

1979, 1989, and 1995 90

H-7. Percentage Distribution of Working-Age and All Married

Couples by Division of Earnings Between Spouses and Age

of Older Spouse in 1969, 1979, 1989, and 1995 91

H-8. Percentage Distribution of Working-Age and All Married

Couples with Two Earners by Number of Children in 1969,

1979, 1989, and 1995 93

H-9. Percentage Distribution of Working-Age and All Married

Couples by Division of Earnings Between Spouses and

Number of Children in 1969, 1979, 1989, and 1995 94

x FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE: MARRIAGE AND THE FEDERAL INCOME TAX June 1997

FIGURES

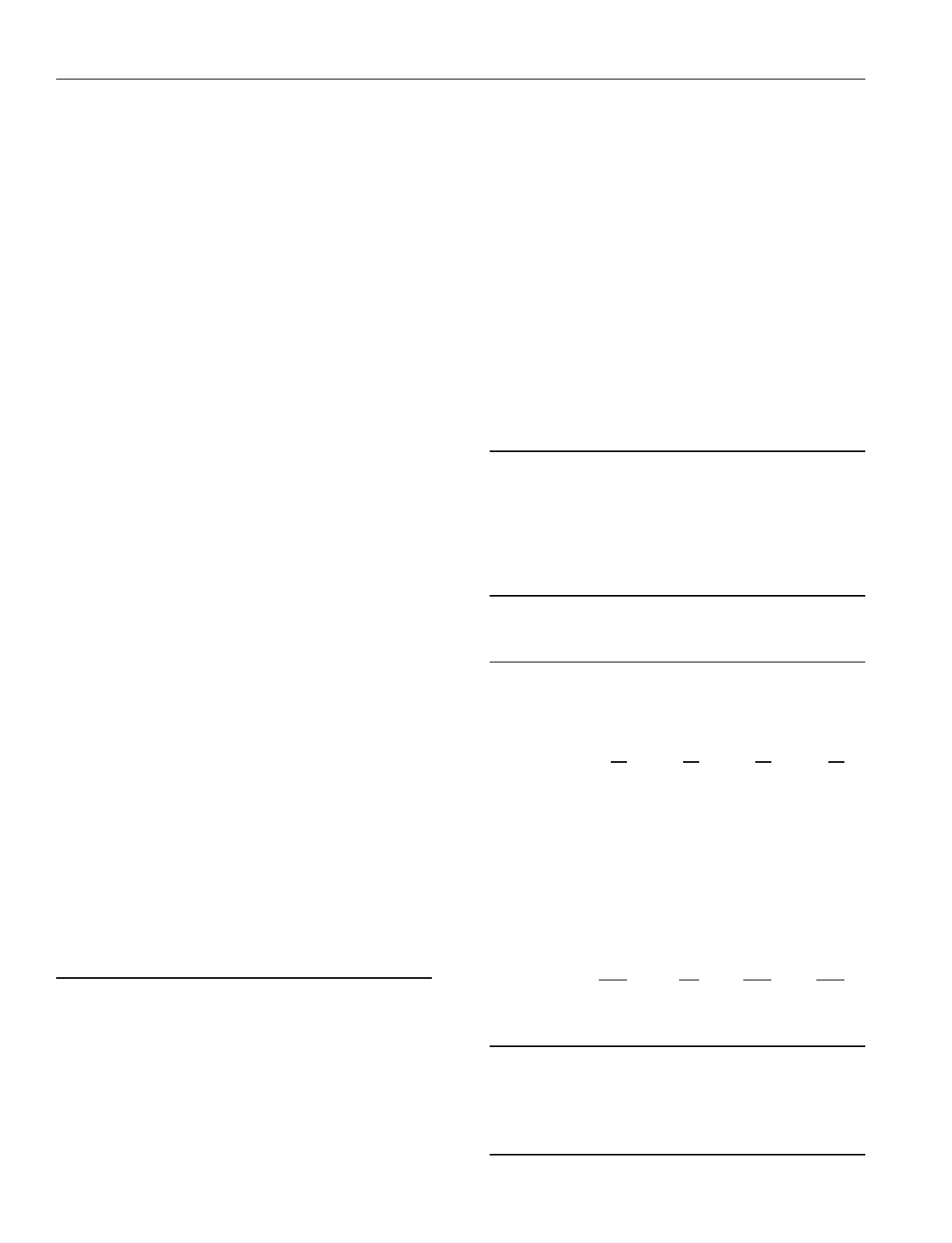

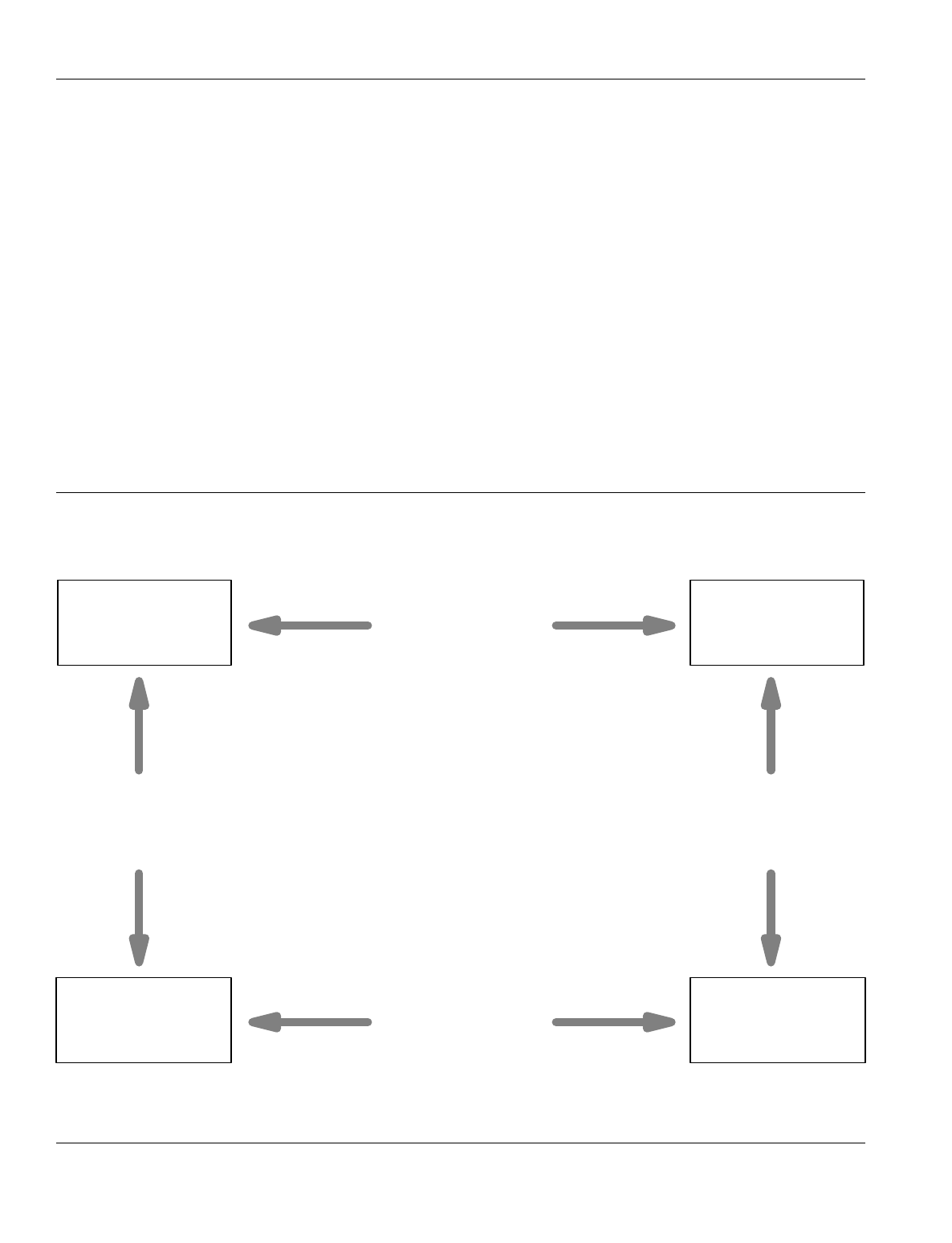

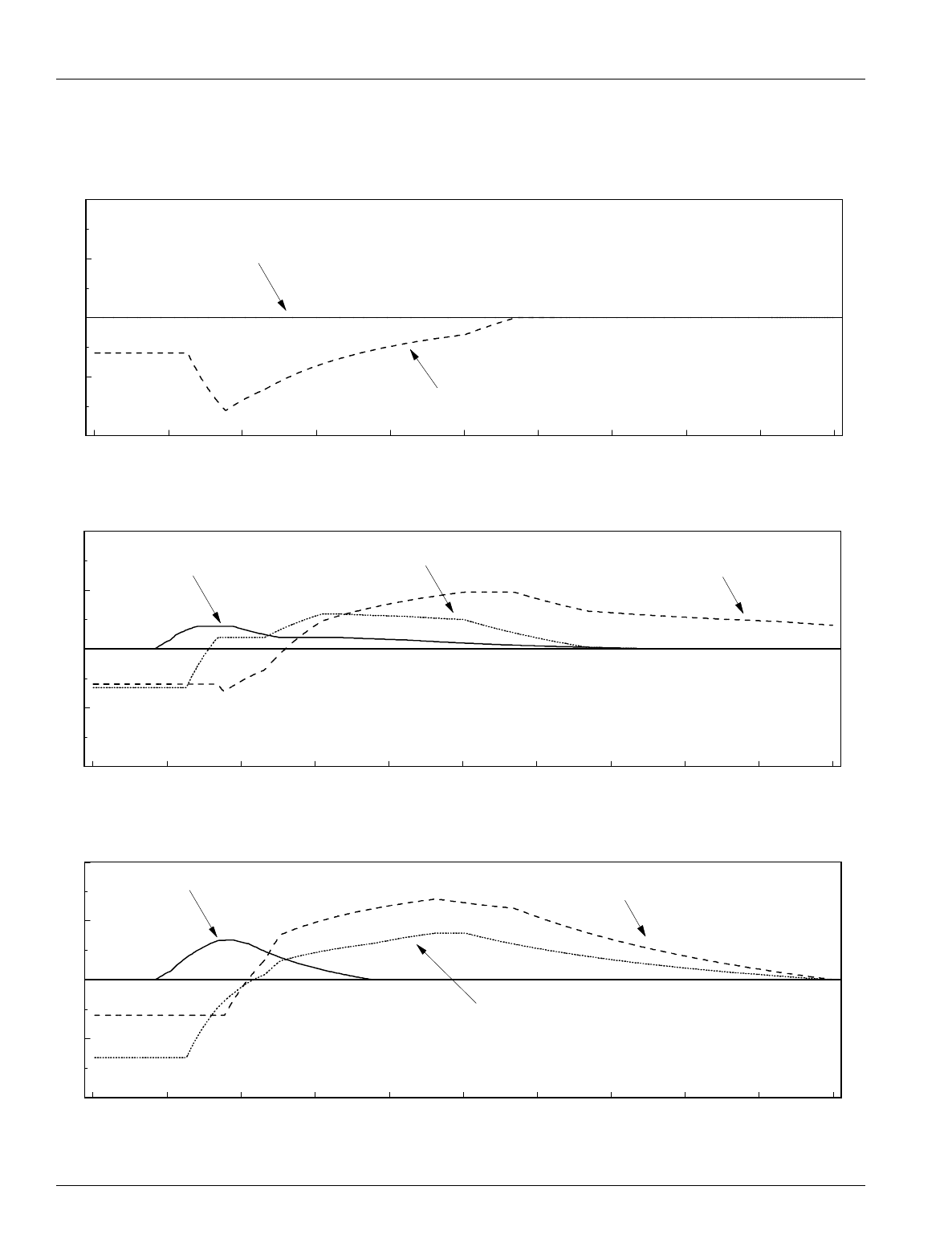

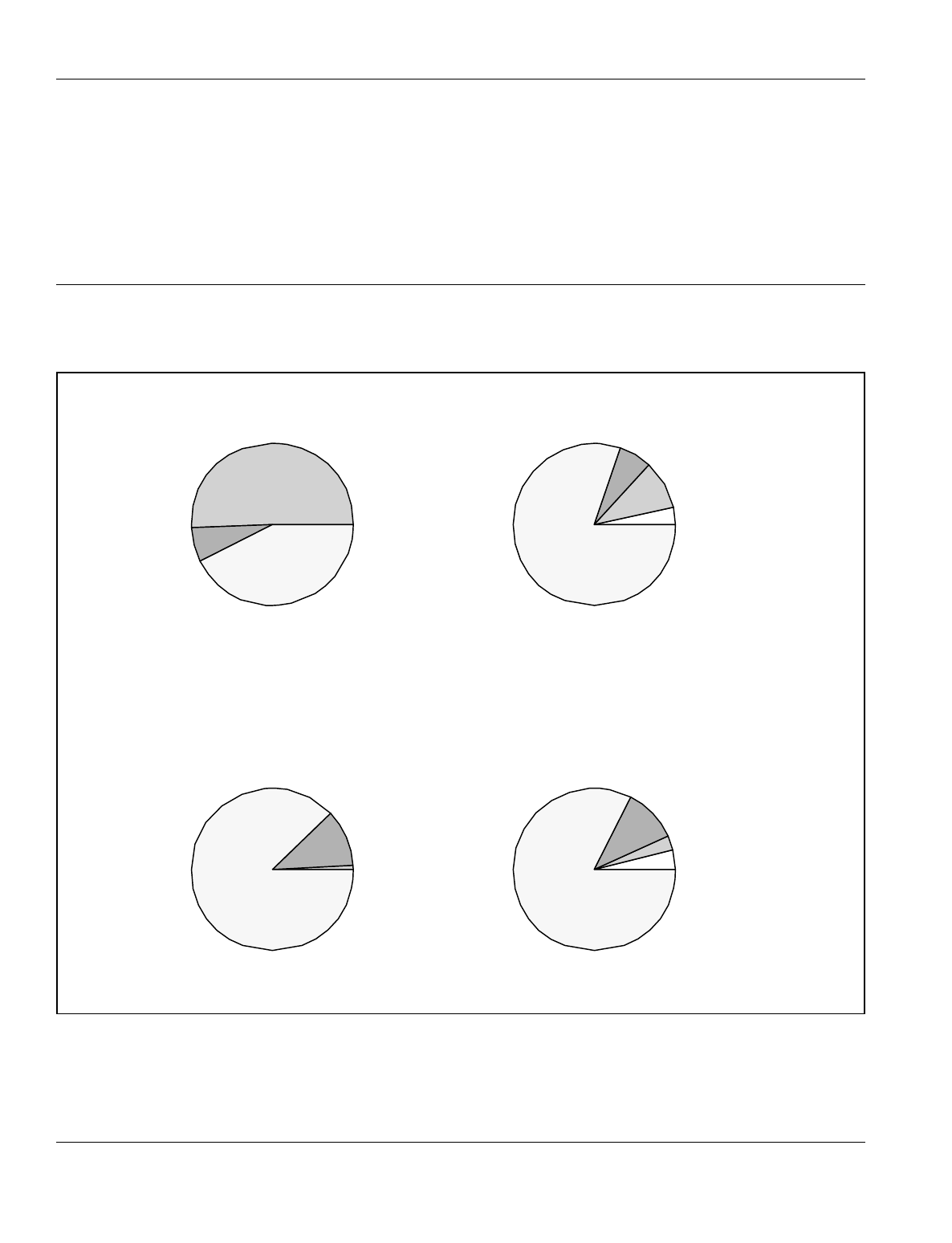

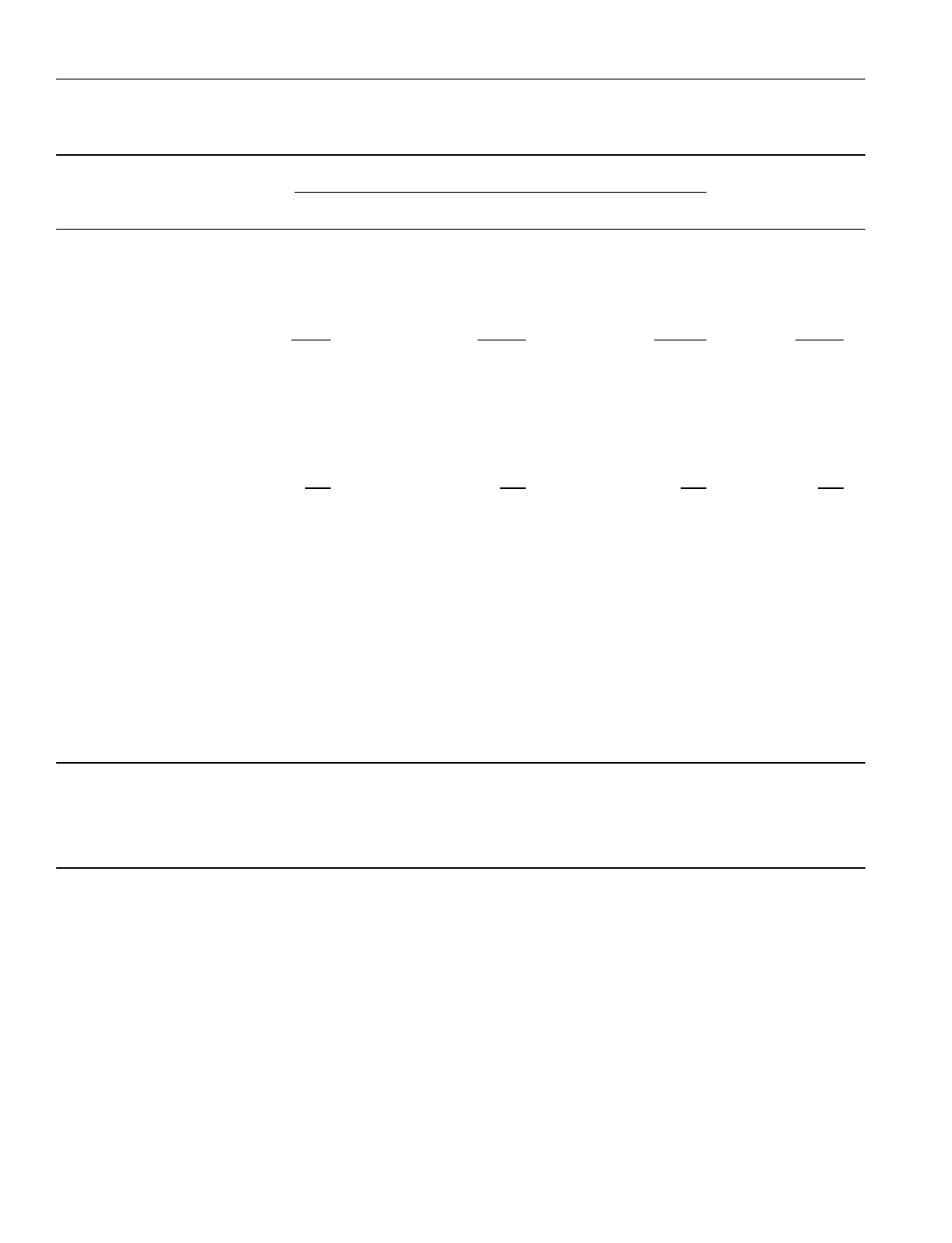

1. The Conflict Among Goals of Income Taxation 3

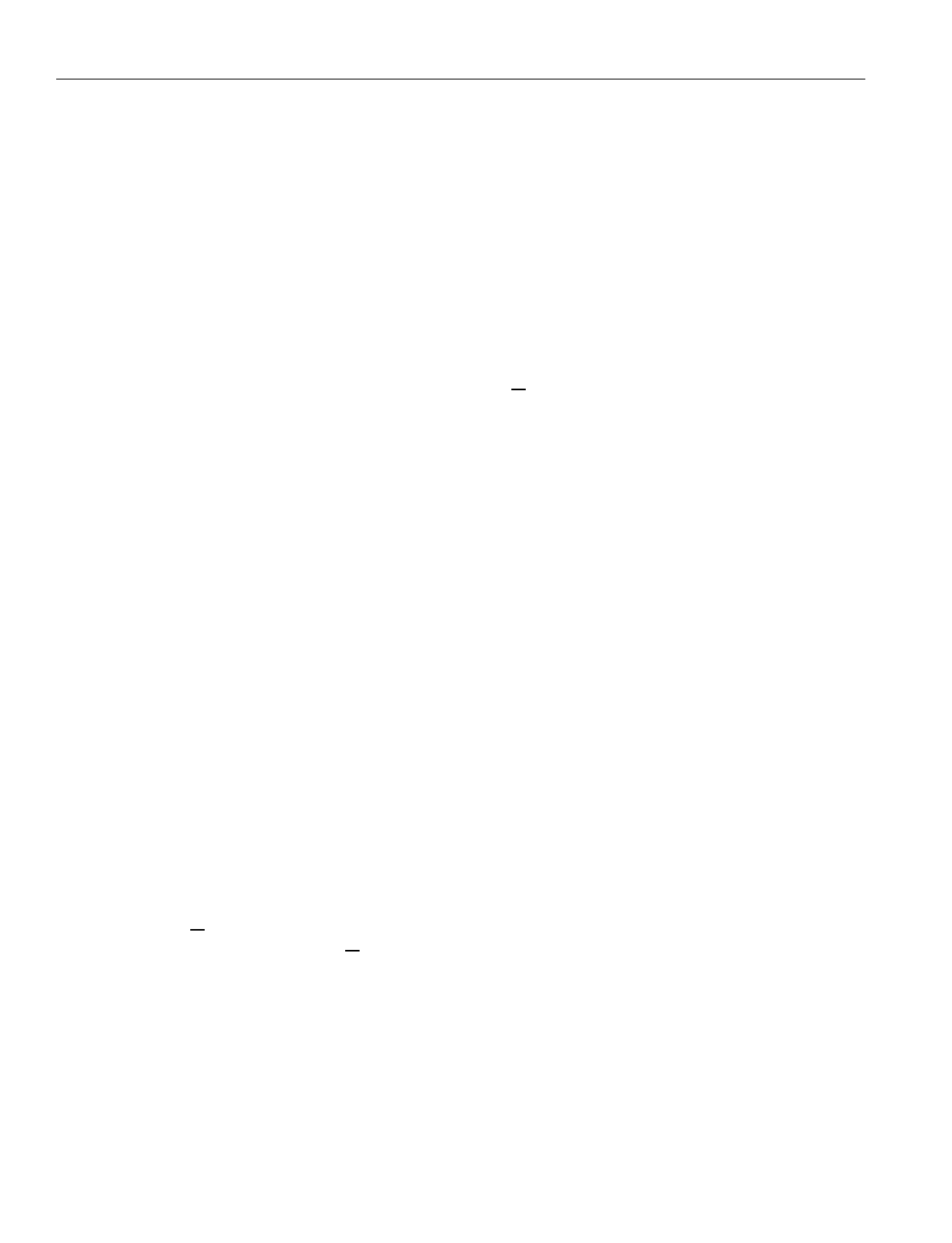

2. Earned Income Tax Credit by Number of Children

and Earnings, 1996 Tax Law 20

3. Marriage Penalties and Bonuses Resulting from the

Earned Income Tax Credit, 1996 Tax Law 22

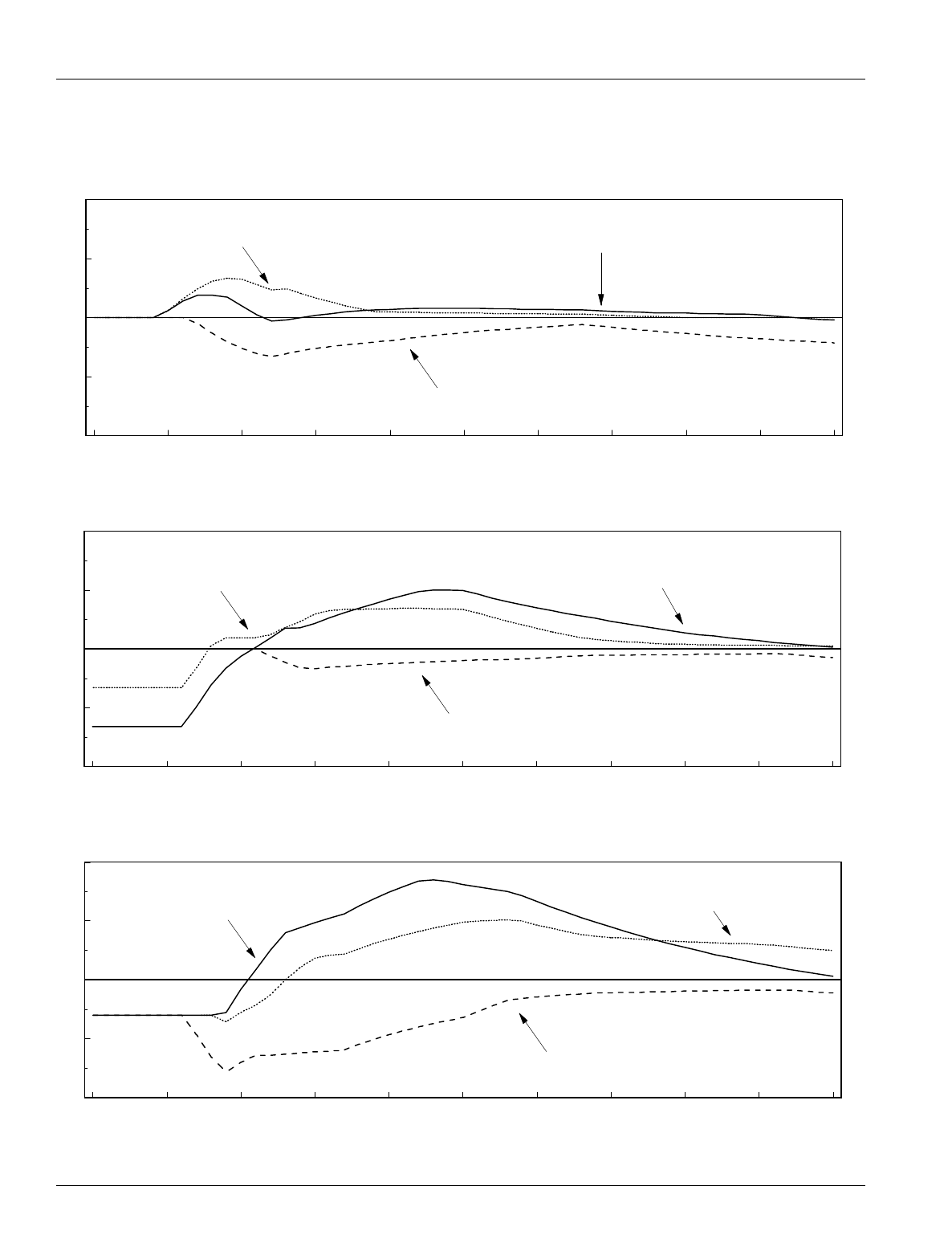

4. Marriage Penalties and Bonuses by Number of

Children and Earnings Split, 1996 Tax Law 24

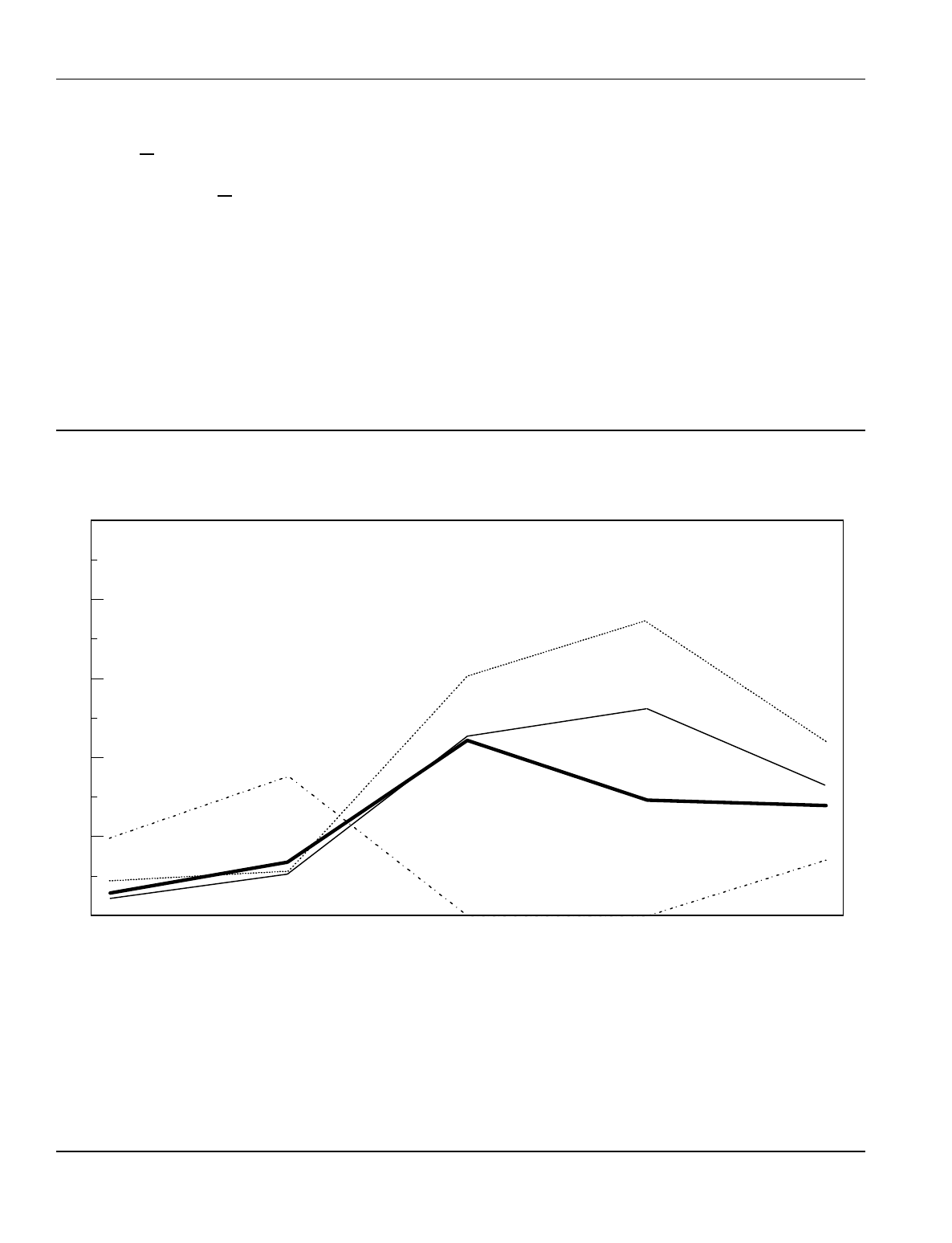

5. Work Patterns of Married Couples, 1969-1995 37

6. Distribution of Families and Unrelated Individuals

by Type, 1969-1995 38

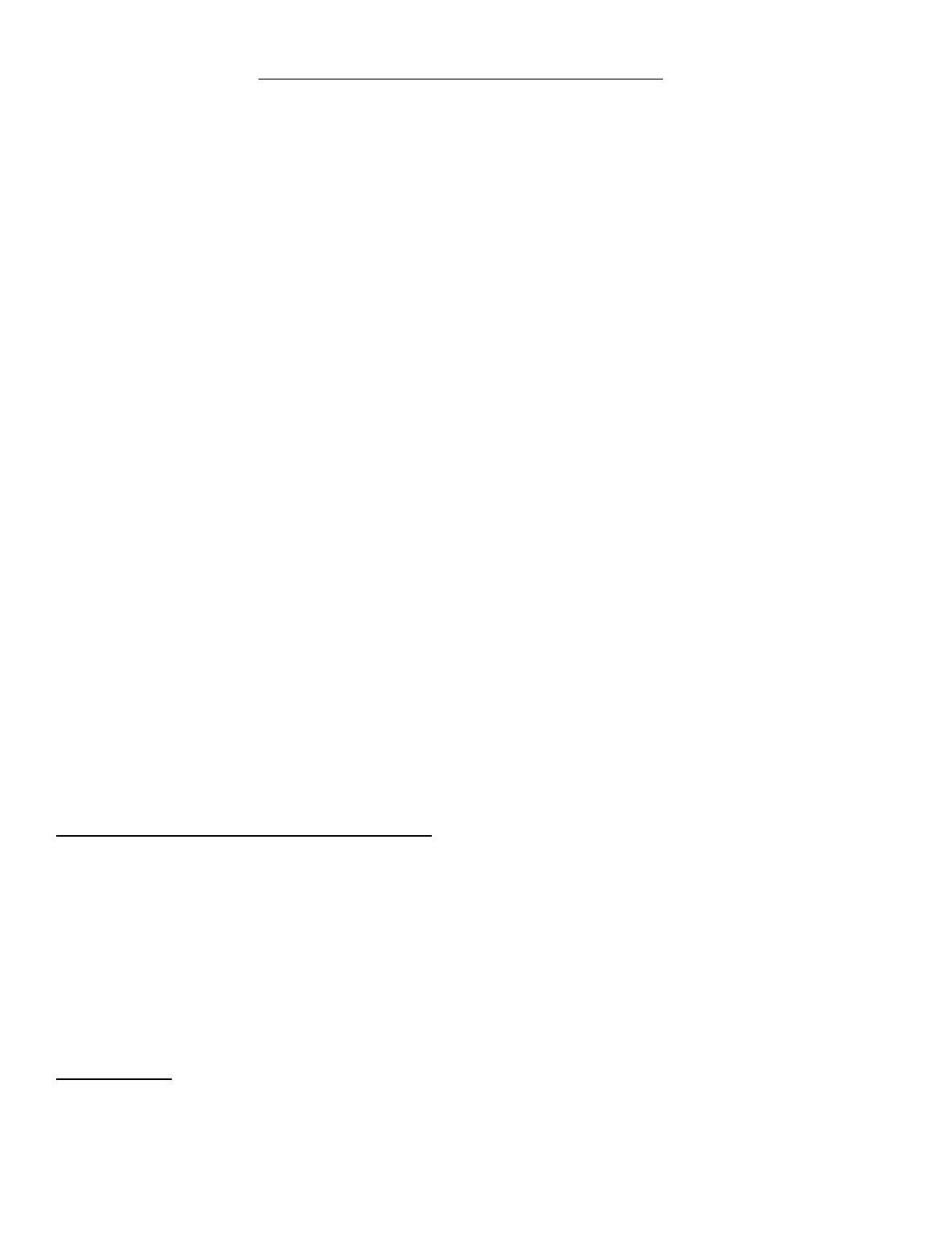

7. Projected 1996 Marriage Penalty Relief Under Alternative

Proposals, Basic Measure of Marriage Penalty 49

8. Projected 1996 Target Efficiency of Alternative Proposals

to Relieve Marriage Penalties, Basic Measure of Marriage

Penalty 50

BOXES

1. A Marriage Penalty 4

2. A Marriage Bonus 5

3. 1996 Marriage Bonuses Resulting from Tax Brackets

for One-Earner Couples 18

4. 1996 Marriage Penalties Resulting from Tax Brackets

for Two-Earner Couples in Which Spouses Have

Equal Earnings 19

5. A Marriage Penalty for a Low-Income Couple

with Children 21

6. Alternative Measures of Marriage Penalties

and Bonuses 29

7. Setting Tax Brackets and Standard Deductions for

Joint Filers to Twice Those for Single Filers 48

8. The Two-Earner Deduction 52

CONTENTS xi

A-1. Tax Treatment of Earned Income in OECD Countries, 1993 60

B-1. Treatment of Married Couples Under State Income

Taxes, 1993 62

M

Summary

arriage affects the income taxes people pay,

sometimes causing married couples to pay

more than they would if they were single and

sometimes causing them to pay less. That is because

the household the married couple or the single indi-

vidual is the basic tax-paying unit in the U.S. system.

Differences in the tax liabilities of households reflect

attempts by the Congress to maintain balance in tax

treatment among different kinds of families. On the

one hand, the tax code seeks to levy the same tax on

couples with the same income, regardless of who earns

the income. On the other hand, the code tries to mini-

mize the effect of marriage on a couple's tax liability.

A tax structure with progressive rates, however, cannot

attain both goals. The incompatibility of those three

goals progressive rates, equal treatment of married

couples, and marriage neutrality results in a continu-

ing tension within the tax code. The third goal, mar-

riage neutrality, has proven to be the most elusive in

our system.

The balance among the goals has shifted over time,

partly in response to complaints of unfair treatment and

partly in reaction to changing demographic patterns.

Growing numbers of single taxpayers, the greater like-

lihood that husbands and wives both work, increasing

parity of earnings for husbands and wives who do

work, and changes in tax rate brackets have all contrib-

uted to the pressures on the balance.

Differences in income tax liabilities caused by mar-

ital status are embodied in a number of tax code provi-

sions, beginning with separate rate schedules for mar-

ried couples and single individuals. The most impor-

tant other differences are those in the standard deduc-

tion and the earned income tax credit (EITC). Those

factors cause most two-earner couples in which hus-

band and wife have roughly equal incomes to pay more

tax than they would if they could file individual tax re-

turns, incurring what has become known as a "marriage

penalty." At the same time, couples with just one

earner or in which husband and wife have quite differ-

ent incomes generally pay lower taxes as joint tax filers

than they would if they could file as single taxpayers.

Those couples receive what analysts have termed "mar-

riage bonuses."

Marriage penalties also exist outside the federal

income tax in the form of transfer program rules that

limit married couples' benefits to amounts below what

they would receive as single individuals. For example,

a low-income single mother might qualify for welfare

assistance, food stamps, and Medicaid, benefits that she

would lose if she obtained a good-paying job or married

a man who had a moderate income. That loss of bene-

fits can offset much of the income gains from work or

marriage, thus providing disincentives for each. Al-

though such marriage penalties outside the tax code can

be substantial and often are larger than those created

by the tax code this study addresses only the different

income taxes paid by joint and individual filers.

If marriage penalties and bonuses were small, they

would be of little consequence. Taxpayers would not

perceive as unfair the small differences in taxes created

by marriage. Perhaps more important, those differ-

ences would not lead people to change their behavior

toward work or marriage itself. But the penalties and

bonuses can be large. Empirical evidence indicates that

they may affect work patterns, particularly for a cou-

xiv FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE: MARRIAGE AND THE FEDERAL INCOME TAX June 1997

ple's second earner. Joint tax filing often imposes a

substantially higher rate on a couple's second earner

than does individual filing. The higher rates reduce the

after-tax wage and may cause second earners to work

fewer hours or not to work at all, thus reducing eco-

nomic efficiency. Furthermore, large differences in tax

liabilities between otherwise similar couples lead to

perceptions of unfairness and calls for changes in the

tax code that would reduce those differences.

The size and imposition of marriage penalties and

bonuses depend on which components of the tax code

are included in their measurement. In general, the more

components of the code that are included in the yard-

stick, the more couples incur marriage penalties and the

fewer couples receive bonuses. The components in-

cluded depend on which taxpaying circumstances are

assumed. The measure used in this study includes the

code components that account for the bulk of the pen-

alty and bonus amounts. The estimates of those penal-

ties and bonuses, however, assume no induced changes

in labor supply or marriage and thus underestimate the

economic costs involved.

To be more specific, marriage penalties and bo-

nuses occur because the tax code allows different stan-

dard deductions in determining the taxable incomes of

couples and single taxpayers, has different tax rates for

given levels of taxable income for the two groups, and

provides the EITC without regard to marital status.

Couples in which spouses have similar incomes gener-

ally can claim smaller deductions, face higher marginal

tax rates, and lose some or all of the EITC they would

have if they filed individual tax returns and thus in-

curred marriage penalties. Couples in which one

spouse earns much less than the other or does not work

face the opposite situation. They may qualify for larger

deductions, incur lower tax rates, and receive more

EITC than under individual filing and thus receive mar-

riage bonuses.

Distribution of

Marriage Penalties

And Bonuses

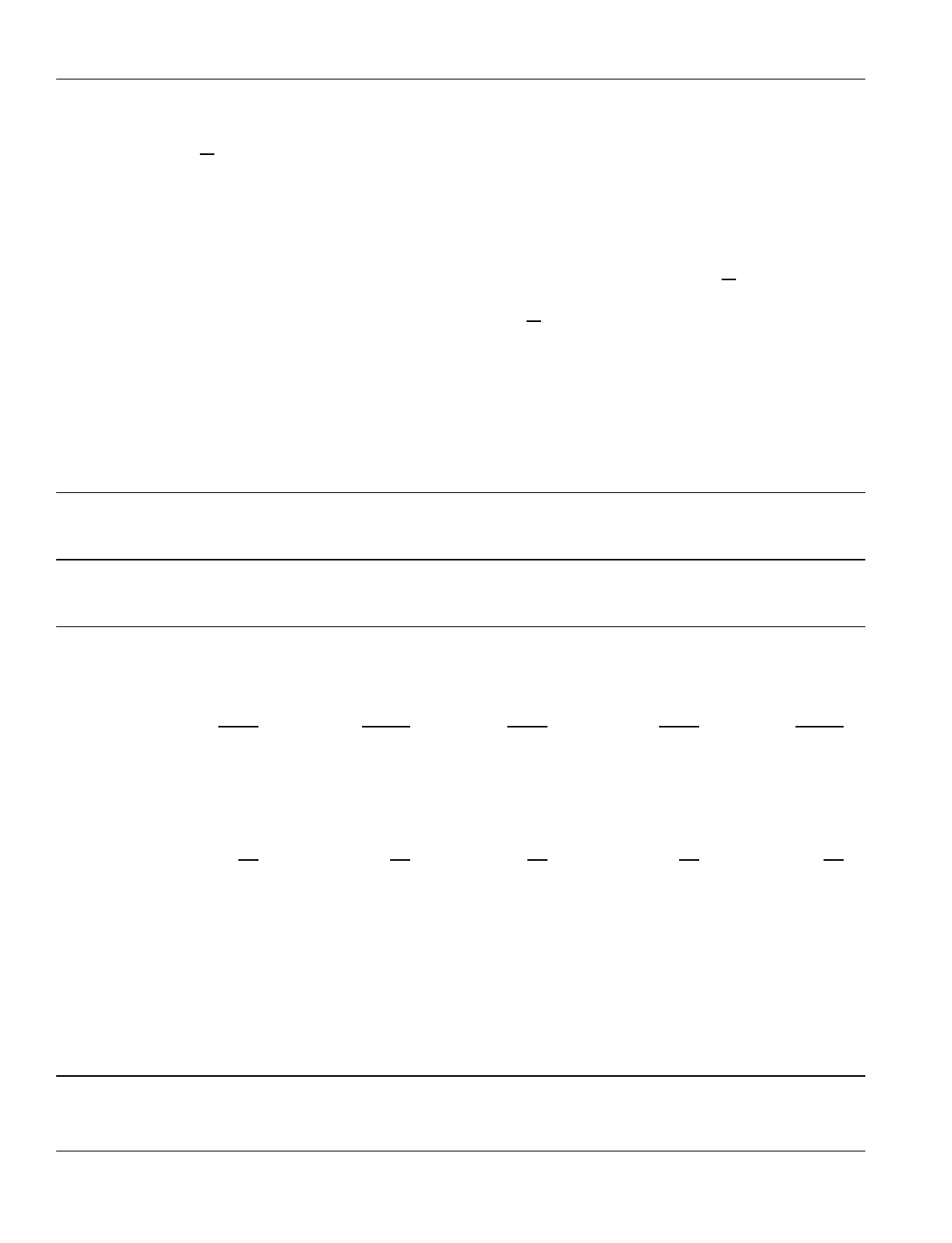

An estimated 42 percent of couples incurred marriage

penalties in 1996, 51 percent received bonuses, and 6

percent paid taxes unaffected by their marital status

(see Summary Table 1). That distribution varies mark-

edly across the income distribution. Only 12 percent of

couples with incomes below $20,000 had penalties and

63 percent received bonuses. Couples with incomes

between $20,000 and $50,000 were somewhat more

likely to receive bonuses than to incur penalties,

whereas couples with incomes above $50,000 were

somewhat more likely to incur penalties than to receive

bonuses.

Measured as a percentage of income, marriage pen-

alties and bonuses are largest for low-income families

and least for high-income families (see Summary

Table 1). Couples with incomes below $20,000 who

bear penalties are estimated to pay nearly 8 percent

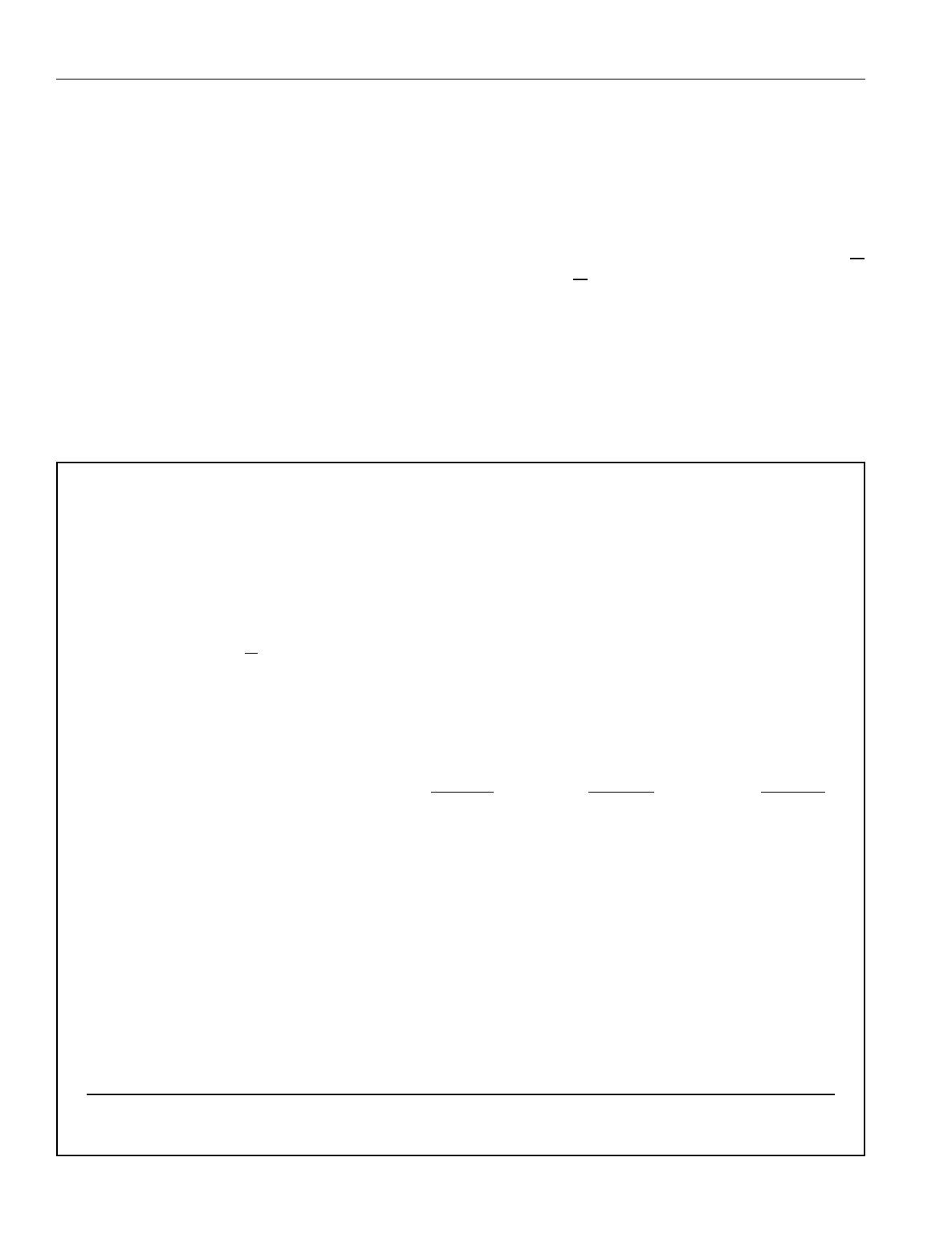

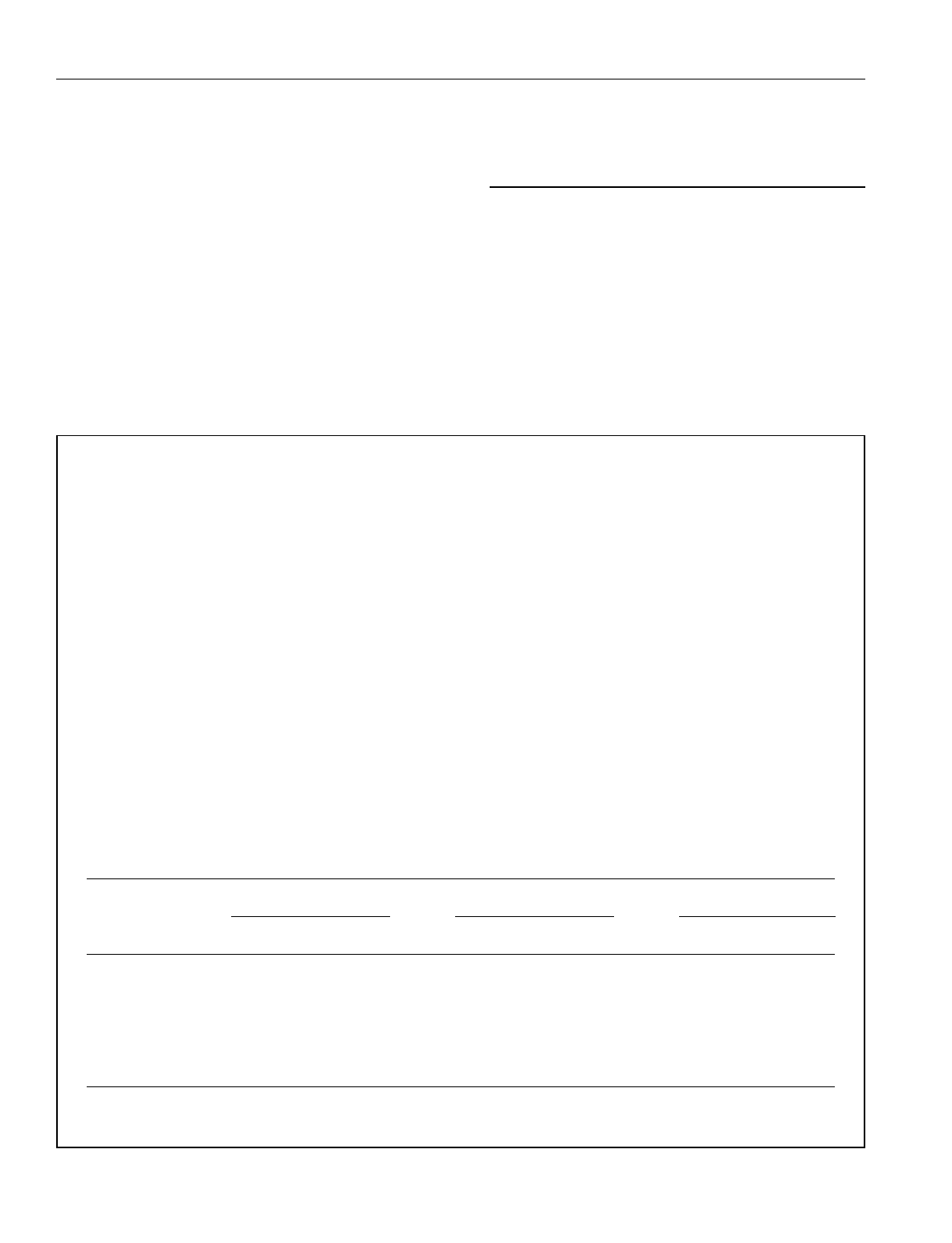

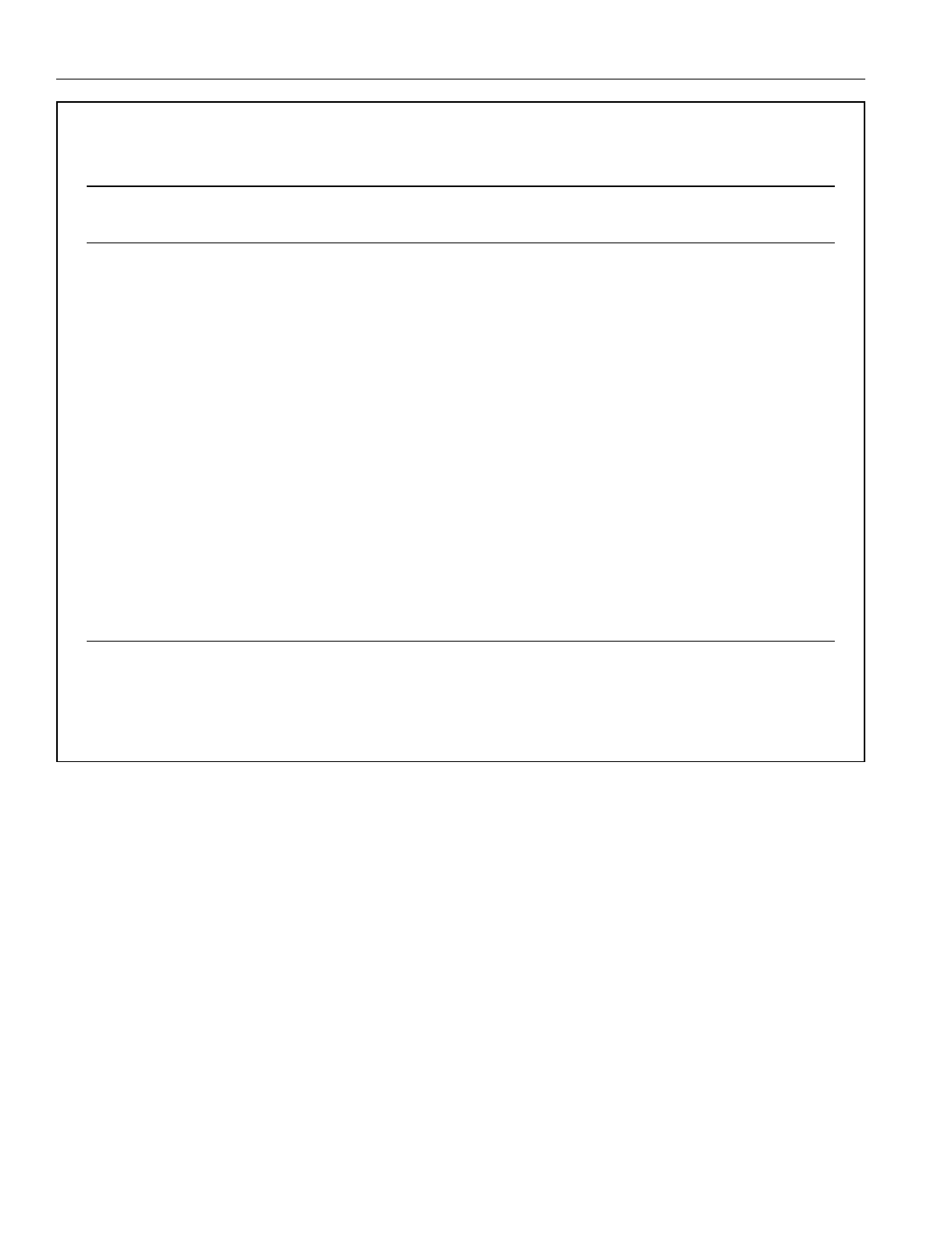

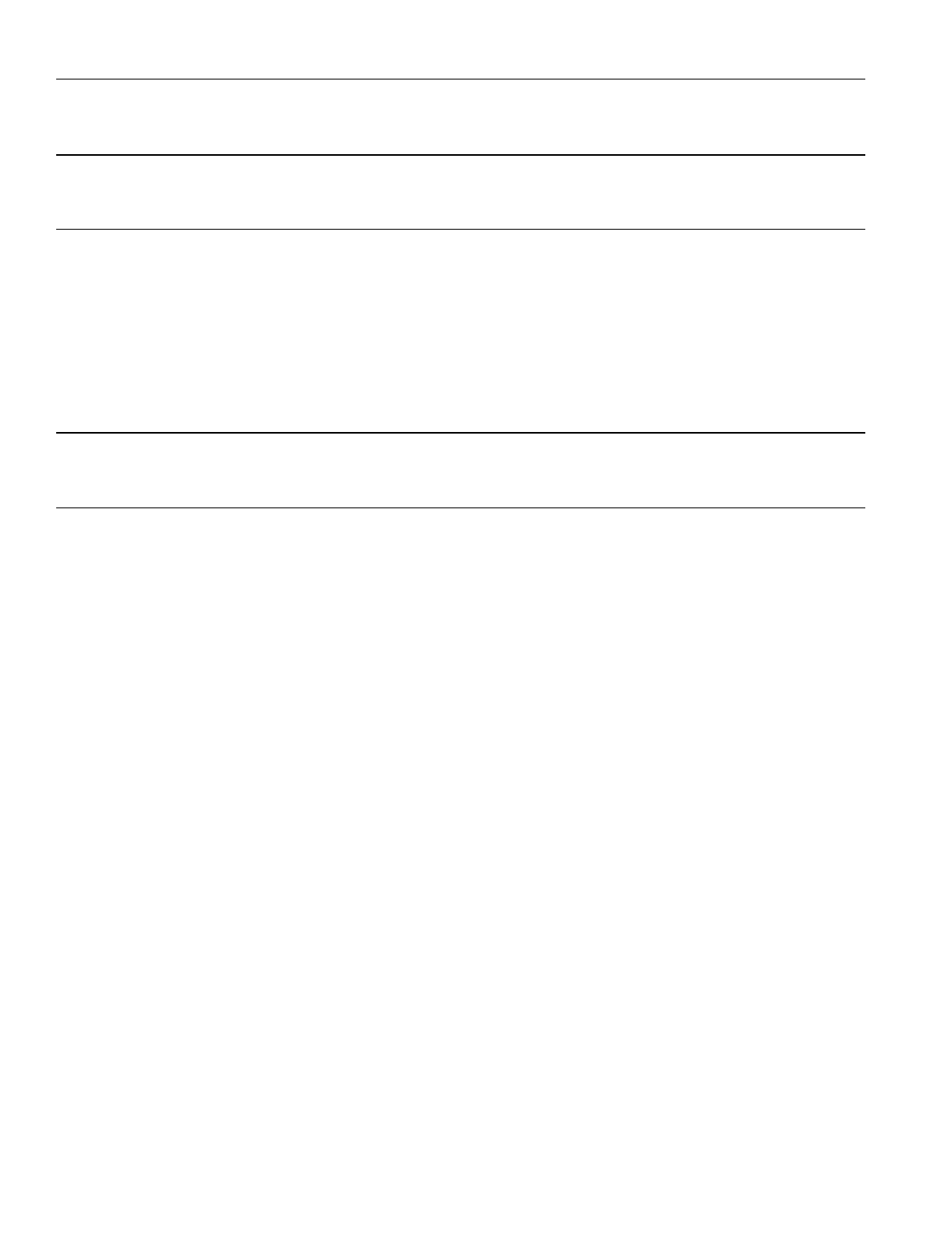

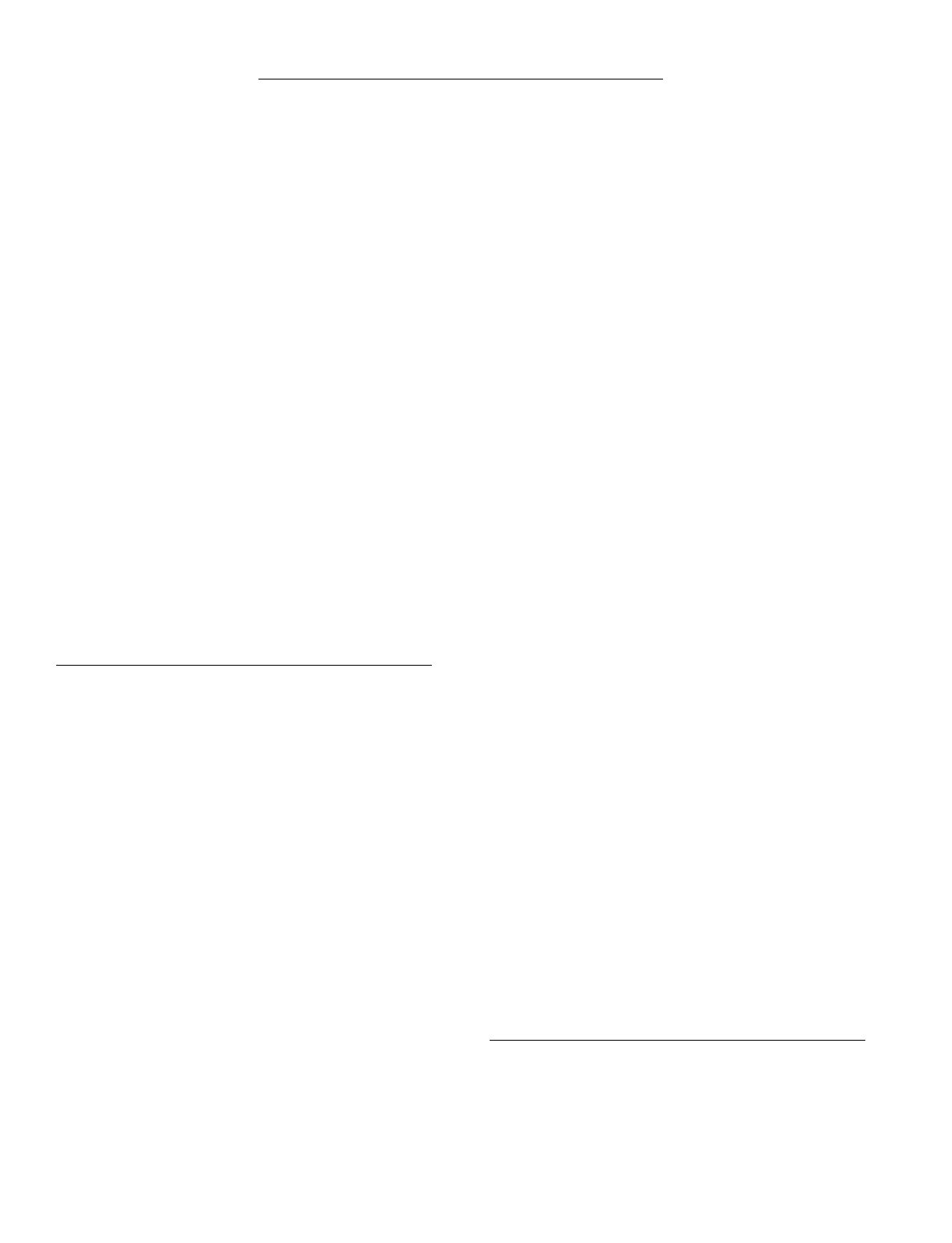

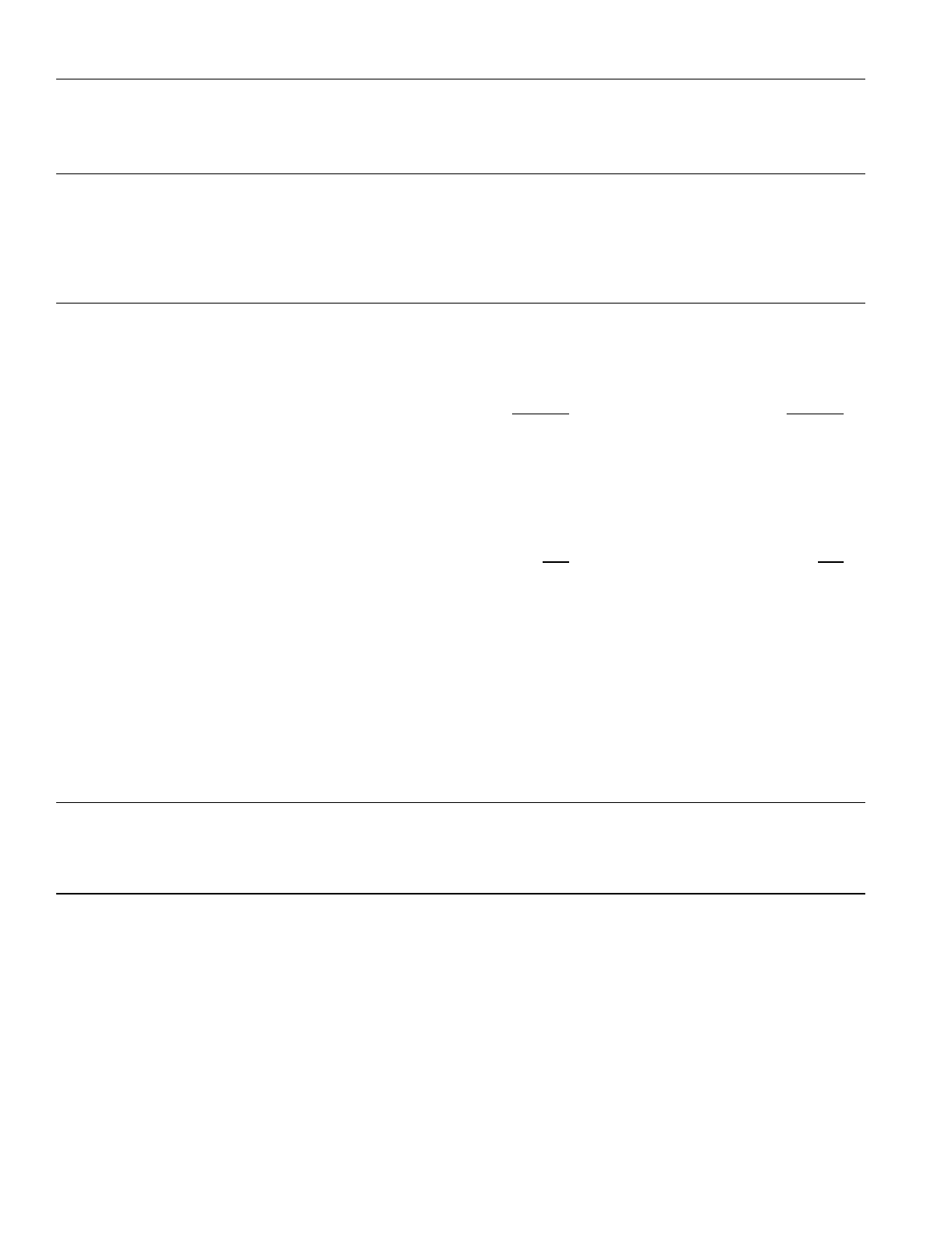

Summary Table 1.

Distribution of Joint Tax Returns and Marriage

Penalty or Bonus as a Percentage of Adjusted

Gross Income, by Adjusted Gross Income of

Couple and Penalty or Bonus Status,

Projected 1996

Less Than $20,000- More Than All

$20,000 $50,000 $50,000 Incomes

Returns in Income Category (Percent)

With Penalties12445442

Unaffected 25136

With Bonuses 63

55 44 51

All Returns 100 100 100 100

Penalty or Bonus as a Percentage

of Adjusted Gross Income

Penalties 7.6 3.2 1.6 2.0

Bonuses 5.0 2.6 2.0 2.3

Total Penalties and Bonuses (Billions of dollars)

Penalties 0.9 9.6 18.3 28.8

Bonuses 3.9

8.7 20.3 32.9

Net Effect on

Tax Liability -3.0 0.9 -2.0 -4.1

a

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office simulations based on data

from the 1993 Statistics of Income.

a. Positive values indicate net penalties; negative values indicate net

bonuses.

SUMMARY xv

more of their income in taxes measured at 1996 income

levels than they would pay if they could file individual

tax returns. For their counterparts who received them,

however, bonuses averaged 5 percent of income. Be-

cause bonus recipients in that income category far out-

number those incurring penalties, low-income married

couples received a net bonus of $3 billion. Both penal-

ties and bonuses for middle-income couples averaged

roughly 3 percent of the incomes of affected families.

Slightly higher average penalties offset a slightly lower

proportion of couples with penalties, yielding a net pen-

alty of nearly $1 billion. Couples with incomes over

$50,000 received a total net bonus of $2 billion. Cou-

ples with bonuses saved 2 percent of their incomes by

filing jointly, more than offsetting the added taxes

equal to 1.6 percent of income paid by penalized

couples.

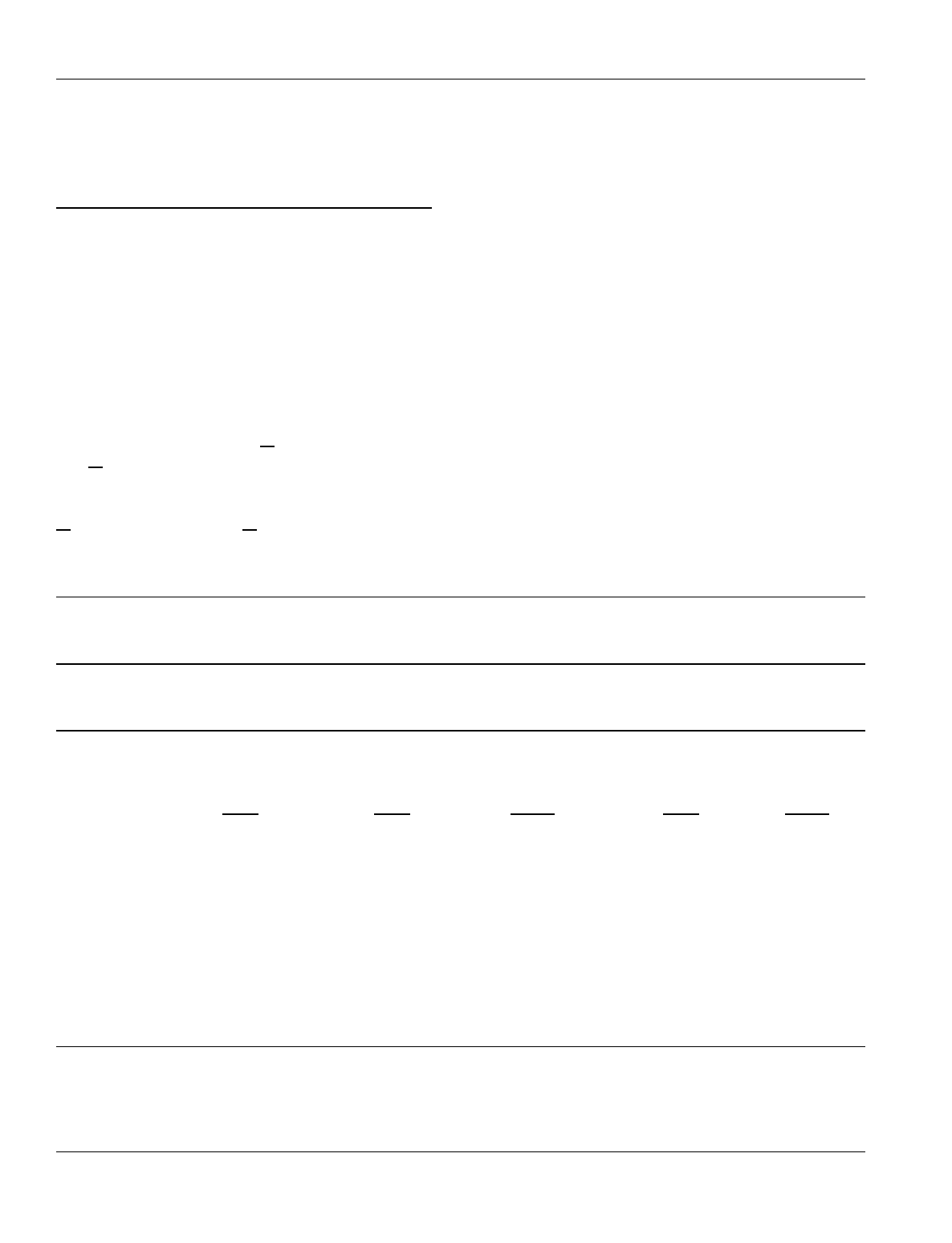

Couples with a more equal division of incomes be-

tween husband and wife are more likely to incur mar-

riage penalties and less likely to receive bonuses than

couples in which one spouse has significantly less in-

come than the other or does not work at all. One-earner

couples received seven-eighths of the total value of bo-

nuses in 1996 but represented less than one-half of all

couples (see Summary Table 2). On net, their income

tax liabilities were nearly $29 billion lower than if they

were required to file individual tax returns. By

contrast, the one-quarter of all couples in which hus-

band and wife both earn at least one-third of the cou-

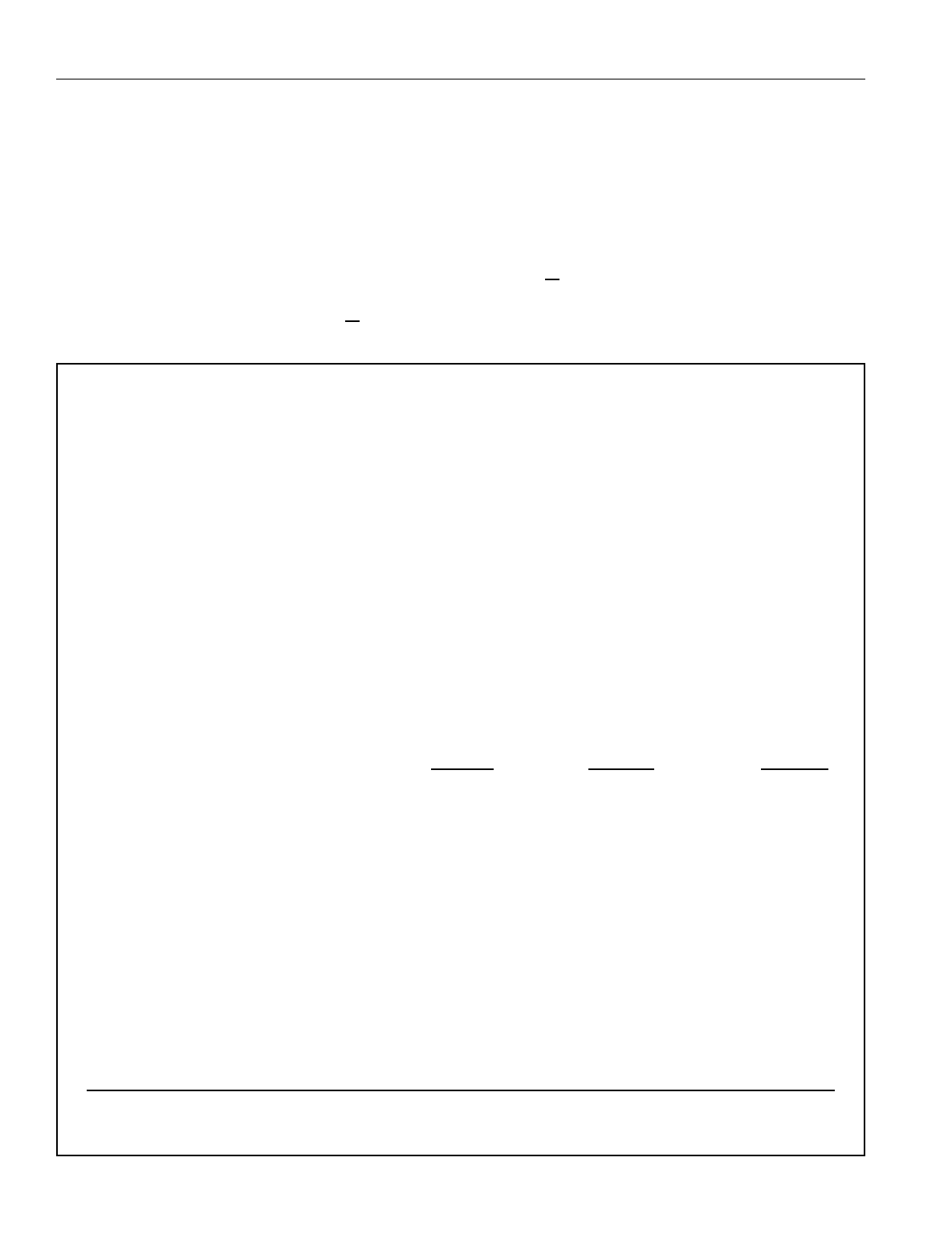

Summary Table 2.

Joint Tax Returns by Penalty or Bonus Status and Division of Earnings Between Spouses, Projected 1996

Both Spouses

Each Spouse Had Earnings

Earned and One Spouse

at Least Contributed Only One

One-Third of More Than Spouse

Couple's Two-Thirds of Had All

Earnings Couple's Earnings Earnings Couples

a

Joint Returns in Penalty or Bonus Category (Percent)

With Penalties 52 48 0 100

Unaffected 21 5 75 100

With Bonuses 2 21 77 100

All Joint Tax Returns 25 31 44 100

Total Penalty or Bonus (Billions of dollars)

Penalties 15.2 13.6 0 28.8

Bonuses 0.1

4.4 28.5 32.9

Net Effect on Tax Liability 15.1 9.2 -28.5 -4.1

b

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office projections based on data from the 1993 Statistics of Income.

a. Couples with no earners and those with one earner incur similar marriage penalties and bonuses and are thus combined in the analysis. For

simplicity of exposition, the text refers to both types of couples as having one earner.

b. Positive values indicate net penalties; negative values indicate net bonuses.

xvi FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE: MARRIAGE AND THE FEDERAL INCOME TAX June 1997

ple's income filed one-half of all joint returns incurring

marriage penalties but only 2 percent of those receiving

bonuses. As a result, those couples paid $15 billion

more in taxes than they would have if they could have

filed as individuals. Those estimates are based on ob-

served earnings under current tax laws, however, and

do not take account of the costs of couples altering their

work and marriage patterns in response to the tax code.

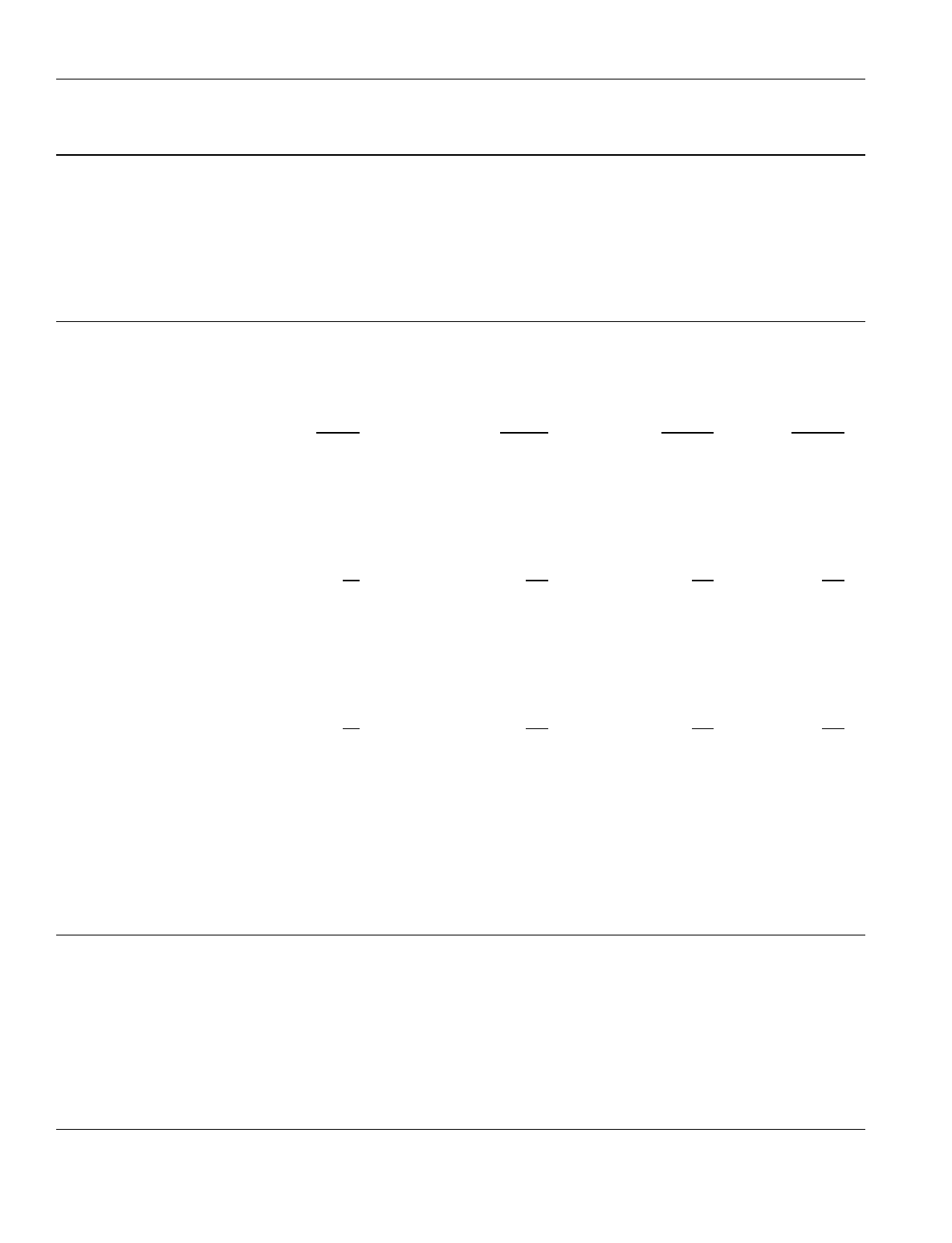

Although the prevalence of marriage penalties and

bonuses indicates that the tax code fails to provide mar-

riage neutrality, it is more successful in achieving equal

treatment of married couples with similar incomes. If

couples were required to file individual tax returns,

those with one earner would face substantially higher

tax rates than those with two earners who have roughly

equal incomes (see Summary Table 3). Because the tax

code generally requires couples to file jointly, those

with different divisions of earnings between spouses

incur more nearly equal tax rates. Marriage penalties

and bonuses arise from this equalization of tax rates for

couples with different divisions of earnings.

Summary Table 3.

Effective Individual Income Tax Rates of

Married Couples Filing Individual or

Joint Returns, Projected 1996 (In percent)

Both Spouses

Each Spouse Had Earnings

Earned and One Spouse

at Least Contributed Only One

One-Third of More Than Spouse

Tax Filing Couple's Two-Thirds of Had

Status Earnings Couple's Earnings Earnings

a

Joint 13.2 15.2 15.0

Individual 11.2 14.3 17.6

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office projections based on data

from the 1993 Statistics of Income.

NOTE: Effective tax rates equal federal individual income tax liability

as a percentage of adjusted gross income.

a. Couples with no earners and those with one earner incur similar

marriage penalties and bonuses and are thus combined in the

analysis. For simplicity of exposition, the text refers to both types

of couples as having one earner.

Demographic Changes

Affecting Marriage

Penalties and Bonuses

In the last two decades, a sharp rise in the share of mar-

ried couples with two earners has taken place, accom-

panied by increasing equality of the earnings of hus-

bands and wives, particularly among couples with

higher incomes. Those changes, occurring for couples

with and without children, have contributed to a rise in

the share of couples incurring marriage penalties.

Between 1969 and 1995, the proportion of working-

age married couples with two workers grew from 48

percent to 72 percent. By itself, that shift tended to

increase marriage penalties and reduce bonuses. Off-

setting that trend, however, was a decline in married

couples as a share of all families and individuals: cou-

ples made up two-thirds of all such tax units in 1969,

but only one-half by 1995. Thus, a smaller fraction of

tax returns are now joint (and hence may be subject to

marriage penalties and bonuses) than was the case a

generation ago.

The shift toward two-earner couples has been ac-

companied by increasing equality of the incomes of

husbands and wives. Between 1969 and 1995, the frac-

tion of working-age couples in which both husband and

wife earned at least one-third of the couple's income

doubled from 17 percent to 34 percent. The greater

equality of spouses' earnings increased both the share

of couples incurring marriage penalties and the size of

those penalties.

Those changes in earnings patterns for married cou-

ples occurred for all subgroups defined by earnings,

age, and presence and number of children. However,

the changes were largest among couples with the high-

est incomes, those with both spouses under age 55, and

those with children.

If the demographic characteristics of married cou-

ples had not changed between 1969 and 1996, more

couples would have received bonuses under 1996 tax

law and fewer would have incurred penalties. Simula-

tions indicate that without the demographic change of

the last quarter century, two-thirds of couples would get

bonuses and less than one-third would pay penalties

SUMMARY xvii

under joint filing, compared with the nearly even split

between the two categories in 1996.

Reducing Marriage Penalties

Recent growth in the number of married couples who

incur marriage penalties and the increasing size of those

penalties have focused attention on the effects of mar-

riage on taxes and on alternative ways to alleviate them.

One approach involves relatively minor alterations of

the current tax code such as changes in tax brackets and

standard deductions, restoration of the two-earner de-

duction, or credits to offset penalties. More significant

changes would allow couples to file either joint or sin-

gle returns or require that all taxpayers file individual

returns. Finally, comprehensive tax reform, replacing

the current income tax with either a simpler tax on in-

comes or some form of consumption tax, would entail

some pattern of penalties and bonuses unless individual

filing was incorporated into the new system.

Changes in the tax code that reduce or eliminate

marriage penalties face an inevitable trade-off: cutting

penalties means lower taxes for some couples and ei-

ther reduced federal tax revenues or higher taxes on

other taxpayers. Revenue-neutral options require a re-

distribution of taxes from those now incurring penalties

to other taxpayers, either couples now receiving bo-

nuses or single people.

Six basic approaches address the problem of mar-

riage penalties directly (see Summary Table 4). Com-

bining options would generate interactions in ways not

analyzed in this study.

o

Widen Tax Brackets and Raise the Standard De-

duction for Joint Filers.

Increasing tax bracket

widths and standard deductions for joint filers to

twice those for single people would reduce total

marriage penalties by nearly one-half at an esti-

mated revenue cost of about $25 billion measured at

1996 income levels. Nearly 90 percent of tax reduc-

tions would accrue to couples with incomes above

$50,000. Half would go to those receiving bonuses

under current law.

o

Exempt from Taxes Some Income of the Lower-

Earning Spouse.

Exempting some earnings of

lower-earning spouses would ease the high marginal

tax rates they may face on even low amounts of

earnings. For example, restoring the 10 percent de-

duction for up to $30,000 of earnings would reduce

total marriage penalties by one-third at an estimated

cost of about $9 billion in lost revenues measured at

1996 income levels. Principal beneficiaries would

be couples with incomes between $50,000 and

$100,000, for whom penalties would fall by more

than one-half. Couples with lower incomes would

see their penalties decline by about one-tenth.

o

Modify the EITC to Reflect Number of Adult Earn-

ers.

A significant share of the marriage penalties

incurred by low-income couples is caused by the

loss of EITC when individual incomes are com-

bined. Providing two-earner couples with EITC pa-

rameters double those for single-earner tax units

would reduce marriage penalties for low-income

couples by about one-fourth, producing an estimated

revenue loss of about $4 billion measured at 1996

income levels. Virtually all of the benefits would go

to couples with incomes below $50,000, and less

than 1 percent would go to those now receiving bo-

nuses because of the EITC. Nearly 3.7 million cou-

ples would become newly eligible for the EITC.

o

Require Spouses to File Individual Tax Returns.

Requiring all taxpayers to file single returns would

eliminate all marriage penalties and bonuses, but

would redistribute roughly $30 billion in tax liabili-

ties from couples now receiving bonuses to those

incurring penalties. Marriage would no longer affect

a couple's tax bill. Although revenue gains from

lost bonuses would outweigh revenue lost in elimi-

nated penalties, yielding an estimated $4 billion in

net additional revenue in 1996, changes in the tax

liabilities of couples would be enormous. The 25

million couples now receiving bonuses would pay an

average of $1,300 in added taxes, and 21 million

couples now incurring penalties would find their

taxes down an average of nearly $1,400.

o

Allow Couples to Choose Filing Status.

Allowing

couples to choose to file either jointly or as individu-

als would eliminate all marriage penalties at an esti-

xviii FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE: MARRIAGE AND THE FEDERAL INCOME TAX June 1997

mated cost of about $29 billion in lost revenues

measured in 1996 income levels. All existing mar-

riage bonuses would continue.

A less extreme version of that approach would allow

couples a tax credit based on a simplified calcula-

tion of the marriage penalty they now pay. If that

calculation was limited to earnings, standard deduc-

tions, and a single personal exemption for each

spouse, the resulting credits would cut total mar-

riage penalties by about one-third, producing an es-

timated revenue loss of about $10 billion measured

at 1996 income levels. Couples with incomes above

$50,000 would have their penalties cut by one-half,

whereas low-income couples would be relieved of

just one-tenth of their current penalties, largely be-

cause the credit would ignore the EITC.

o

Fundamental Radical Tax Reform.

Fundamental

changes in the federal tax system such as those dis-

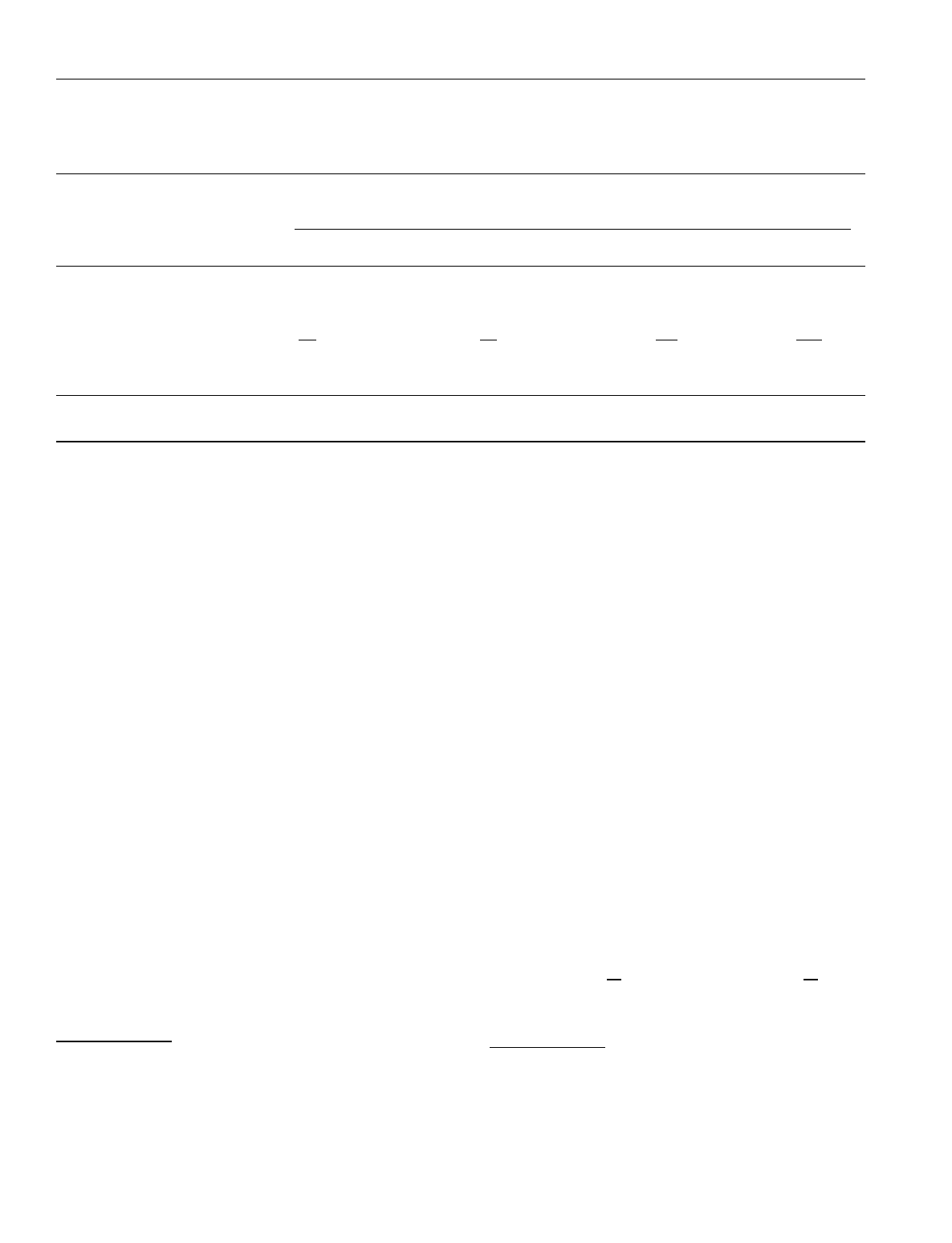

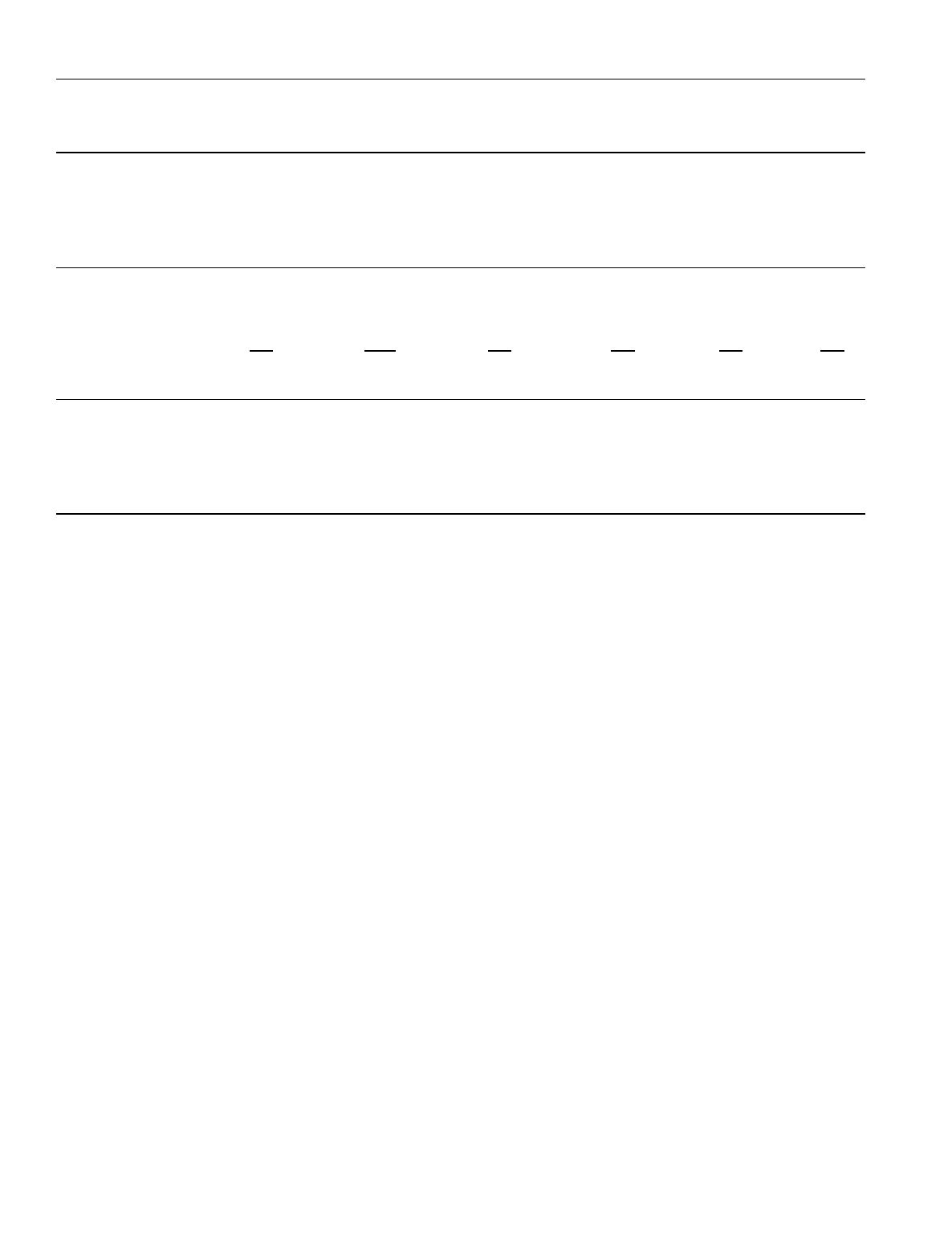

Summary Table 4.

Alternative Approaches to Reducing Marriage Penalties

Share Share to Tax Units (Percent)

of With With

Revenue Loss Penalty Incomes Incomes Currently

a

(Billions of Removed Below Above Receiving

b

Approach dollars) (Percent) $20,000 $50,000 Bonuses

cc d

Set Standard Deduction and Width of

Tax Brackets for Joint Filers Equal to

Double Those for Single Filers 25 44 6 87 51

Restore Two-Earner Deduction 9 32 1 82 10

Double Earned Income Tax Credit

Parameters for Two-Earner Couples 4 12 41 1 1

Require Spouses to

File Individual Returns -4 100 e e e

Allow Couples to

Choose Filing Status 29 100 3 64 0

Replace Income Tax

with Consumption Tax f f f f f

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office simulations.

NOTE: See text for complete description of approaches.

a. Negative value indicates revenue gain because tax increases for some taxpayers exceed tax reductions for others.

b. Total tax reduction for couples currently incurring tax penalty as a percentage of current total tax penalty.

c. Percentage of revenue loss going to couples with income in given range. Share includes tax reductions for couples getting either penalties or

bonuses.

d. Fraction of total revenue loss going to couples currently receiving marriage bonuses.

e. All couples incurring penalties get tax reductions equal to penalties. All couples receiving bonuses incur tax increases equal to bonuses. Shares

going to each income group and to those receiving bonuses are misleading and therefore not shown.

f. Revenue loss depends on formulation of consumption tax. Distribution among income groups and to those now receiving bonuses cannot be

determined.

SUMMARY xix

cussed during the 104th Congress could markedly

reduce marriage penalties. Moving to a flat

(single-rate) tax, for example, would eliminate all

penalties (and bonuses) resulting from tax brack-

ets. If reform also eliminated other tax features

such as standard deductions and the EITC, penal-

ties and bonuses arising from those features would

also disappear. Alternatively, switching from a tax

on income to a tax on consumption would wipe out

all marriage penalties and bonuses if exemptions

from the tax were independent of marital status and

marriage did not affect a couple's combined con-

sumption.

F

Chapter One

Marriage Penalties and Bonuses

ederal income tax laws generally require that a

married couple file a joint tax return based on

the combined income of husband and wife. As

a result, husbands and wives with similar incomes usu-

ally incur a larger combined tax liability than they

would if they could file individually. At the same time,

spouses who have markedly different incomes but file

as a couple generally face smaller tax bills than they

would if they were single. Those two possibilities, of-

ten referred to as marriage "penalties" and "bonuses,"

result from conflicting goals of a tax system that at-

tempts to balance fairness between married and unmar-

ried couples, among married couples, and among tax-

payers with differing incomes.

Under 1996 tax law, a married couple could face a

federal tax bill that was more than $20,000 higher than

the amount they would pay if they were not married and

could file individual tax returns, whereas other couples

may find that filing a joint tax return reduces their tax

bill by more than $4,000. Although there are various

1

ways of defining marriage penalties and bonuses, one

broad measure indicates that more than 21 million mar-

ried couples paid an average of nearly $1,400 in addi-

tional taxes in 1996 because they must file jointly,

whereas another 25 million found that the benefits of

filing jointly decrease their tax bills by an average of

about $1,300. Marriage penalties totaled about $29

billion in 1996, and bonuses added up to roughly $33

billion.

Marriage penalties are a relatively recent aspect of

federal income taxes, the result of changes made in the

tax code in 1969 to redress what some individuals

viewed as unfairly high taxes paid by single people.

Although the impact and size of marriage penalties and

bonuses have changed over the years with changes in

the tax code, recent tax increases in the form of addi-

tional tax brackets, and shifts in the work patterns of

married couples have combined to expand the propor-

tion of couples subject to penalties and boost the mag-

nitude of those payments. Those movements have

raised interest in policies that would reduce the impact

of marriage penalties in the tax code.

Marriage penalties and bonuses are not deliberately

intended to punish or reward marriage. Rather they are

the result of a delicate balance among disparate goals of

the federal income tax system. Largely for historical

reasons, the United States imposes income taxes not on

individuals as do most other industrialized nations, but

on couples, regardless of the division of incomes be-

tween spouses. Under a progressive structure of tax

rates, treating families equally generally means that a

couple's taxes will differ depending on their marital

status. Over time, the ebb and flow of political pres-

sures have shifted the equilibrium between marriage

penalties and bonuses as the Congress has attempted to

balance the competing demands of married and unmar-

ried taxpayers. Shifting demographics, particularly the

1. Federal income taxes are only one source of marriage penalties. Oth-

ers include state and local income taxes and federal transfer programs

such as Social Security, in which benefits depend in part on both mari-

tal status and resources. This study does not consider any effects of

marriage beyond those affecting a couple's federal individual income

tax liability. Two recent studies that examine the broader question

of marriage penalties and bonuses are Linda Giannarelli and Eugene

Steuerle,

The Twice-Poverty Trap: Tax Rates Faced by AFDC Re-

cipients

(Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, April 1995), and Stacy

Dickert-Conlin and Scott Houser,

Taxes and Transfers: A New Look

at the Marriage Penalty

(unpublished working paper, Lexington:

University of Kentucky, July 1996).

2 FOR BETTR OR FOR WORSE: MARRIAGE AND THE FEDERAL INCOME TAX June 1997

growing proportion of couples with two earners, have

exerted further pressures on that fragile equilibrium.

Whether a couple incurs a penalty or receives a bo-

nus in their taxes depends on the level of their income,

the division of earnings between husband and wife, and

how many children they have. Over the last quarter

century, as more wives have entered the labor force and

their wages have risen in relation to men's, earnings of

spouses have grown more equal. The change increases

the likelihood that a couple will incur a tax penalty, as

compared with two single people whose earnings are

the same. Changes in demographics and earnings alone

appear to have increased by one-half the proportion of

couples incurring marriage penalties.

In 1995, the House of Representatives passed legis-

lation that would slightly lower the tax penalty imposed

on married couples, which would have cost $2 billion

annually in reduced government revenues. That same

year the Senate included in its budget reconciliation bill

a provision that would, over a 10-year period, raise the

standard deduction for married couples filing jointly to

twice that of single filers. When fully phased in, that

change would reduce the marriage penalty for many

couples and increase the marriage bonus for others at

an annual cost of roughly $5 billion in lower revenues.

Other options that would further reduce or eliminate

marriage penalties could have significantly higher reve-

nue costs.

Definin

g

Marria

g

e Penalties

and Bonuses

Marriage penalties and bonuses in the federal individual

income tax are defined as the increase or decrease in

taxes that some married couples incur because they pay

taxes as couples rather than as individuals. Penalties

and bonuses result from the tax code's pursuit of three

conflicting goals: equal treatment of married couples,

marriage neutrality, and progressive taxation.

Equal Treatment of Married Couples

According to the principle of equal treatment, married

couples who have equal incomes should pay the same

income taxes, regardless of the way earnings are di-

vided between spouses. Thus, a couple in which each

spouse earns half the income should pay the same taxes

as a couple with the same income but in which only one

spouse works. That concept runs afoul of equity princi-

ples when married couples with equal incomes have

different abilities to pay. A prime example involves

one- and two-earner families with the same total in-

come. Because the nonearning spouse has time to per-

form household tasks, the one-earner couple is better

off than the couple with two workers, which often has

to pay for such services as child care and household

chores. It thus has a greater ability to pay and, by some

standards of equity, should pay higher taxes. But deter-

mining the difference in ability to pay is difficult, if not

impossible, and the government has shied away from

imposing different taxes on that basis.

Marriage Neutrality

Under the principle of marriage neutrality, a couple's

income tax bill should not depend on their marital sta-

tus. Without neutrality, the tax code would provide an

incentive, even though it is small, for couples either to

marry

if marriage would lower their tax bill or to

remain single if marriage increases their taxes. The

concept of marriage neutrality may violate principles of

equity, however, if marriage (or divorce) either in-

creases or decreases couples' combined ability to pay.

If, for example, marriage enables couples to reduce

their housing costs because they live together, marriage

would increase their ability to pay, and in fact some

standards of equity would dictate that they pay higher

taxes than they did before they married.

Progressive Taxation

The principle of progressive taxation holds that taxpay-

ers who have higher incomes should pay a larger per-

centage of their incomes in taxes than do those with

lower incomes. The federal income tax, for example,

imposes no tax on families and individuals who have

the lowest incomes, and taxes income above various

thresholds according to a series of graduated rates rang-

ing from 15 percent to 39.6 percent. Graduated tax

rates, however, are not necessary to achieve progres-

sivity. Combining a single rate and a low-income de-

duction or credit would also be progressive.

Couple A: married

with both spouses

earning $30,000

Same Tax

(Marriage Neutrality)

Same Tax

(Marriage Neutrality)

Same Tax

(Equal Treatment

of Married Couples)

Different Taxes

(Progressivity)

Couple A: not married,

each person

earning $30,000

Couple B: married

with one worker

earning $60,000

Couple B: not married,

one worker

earning $60,000

CHAPTER ONE MARRIAGE PENALTIES AND BONUSES 3

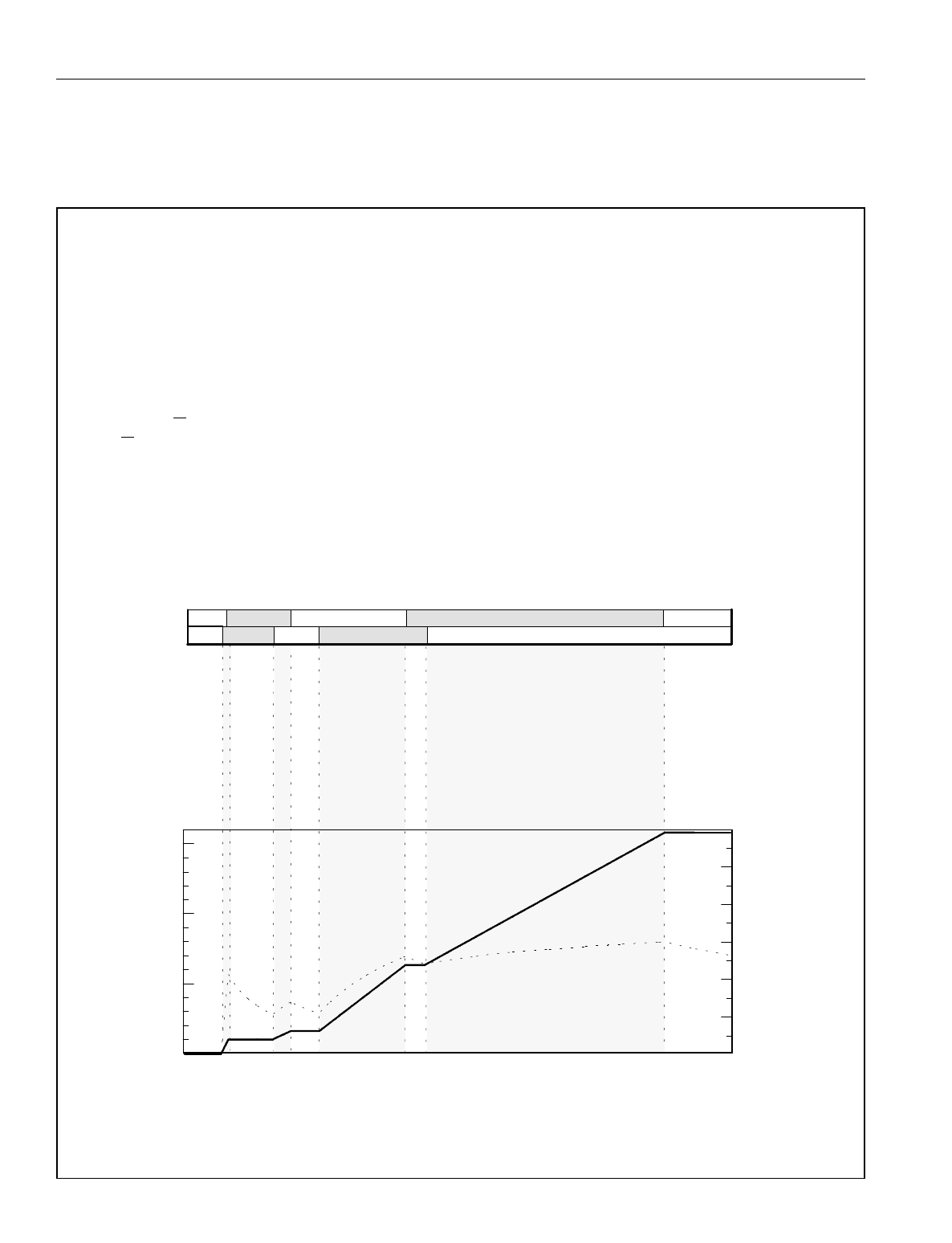

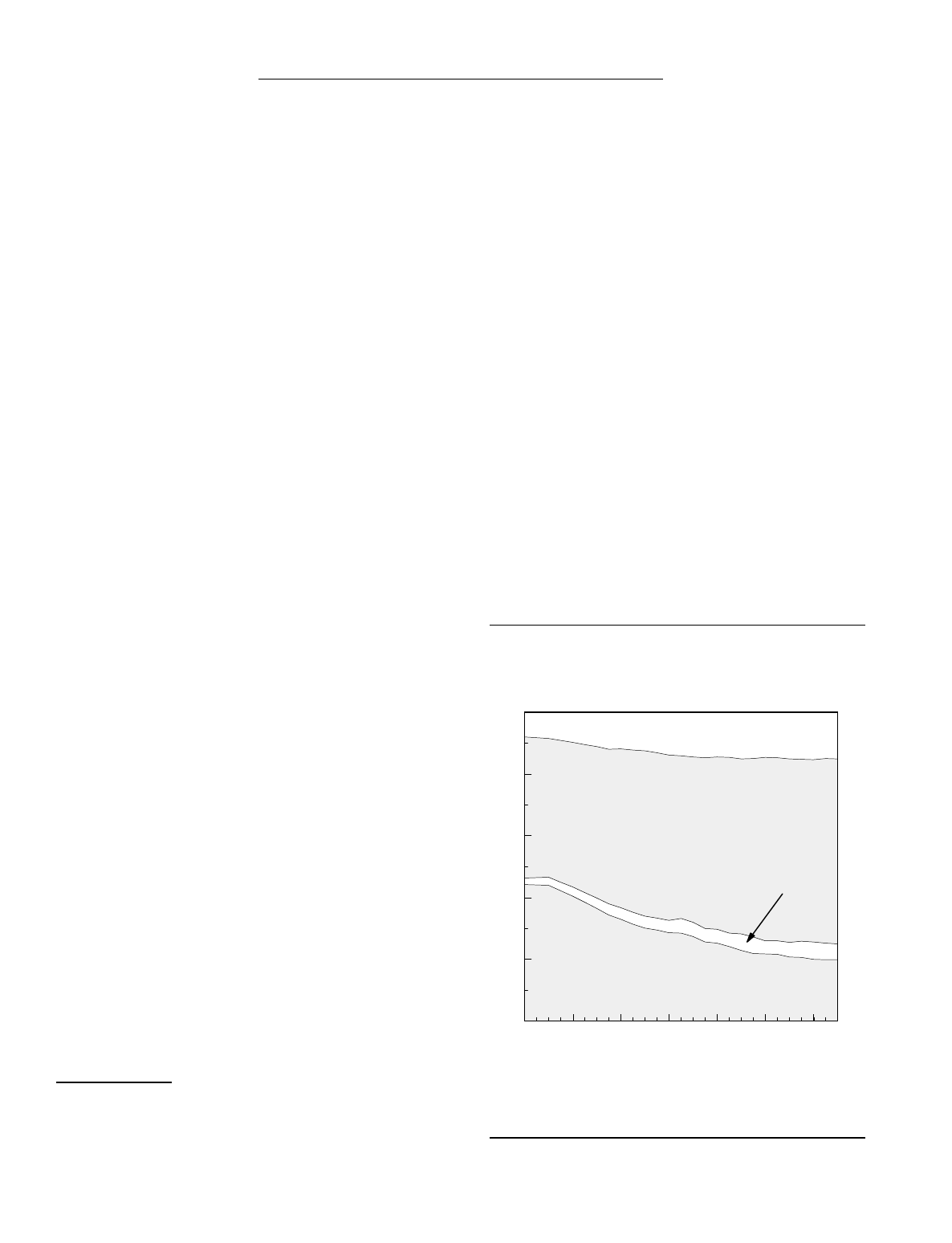

The Unattainable Ideal

A simple example demonstrates the impossibility of

simultaneously achieving all three of those goals (see

Figure 1). Consider two couples, each earning $60,000

and having no unearned income. Both members of cou-

ple A work, each earning $30,000, whereas only one

member of couple B works, earning the couple's entire

$60,000. Satisfying the goal of taxing married couples

with the same incomes equally requires that married

couple A and married couple B pay the same taxes. To

meet the goal of marriage neutrality, the tax bill of each

couple must not depend on their marital status; that is,

the tax on two single people, each earning $30,000,

must equal the tax on a married couple in which each

spouse earns $30,000, and the tax on two single people,

one with a $60,000 income and the other with no in-

come, must equal the tax on a one-earner married cou-

ple with the same $60,000 income.

Combining the two goals implies that two single

people, each with a $30,000 income, pay the same total

tax as two single people, one earning $60,000 and the

other with no income, or, equivalently, that a single per-

son with a $60,000 income pay exactly double the tax

of a single person earning $30,000. But that outcome

directly violates the goal of progressive taxation: under

that principle, a person who has twice the income of

another pays more than twice the taxes.

Relaxing one or more of the three goals solves the

contradiction among them. Forgoing progressivity, for

example, would allow a tax system to satisfy both the

goal of marriage neutrality and that of equal treatment

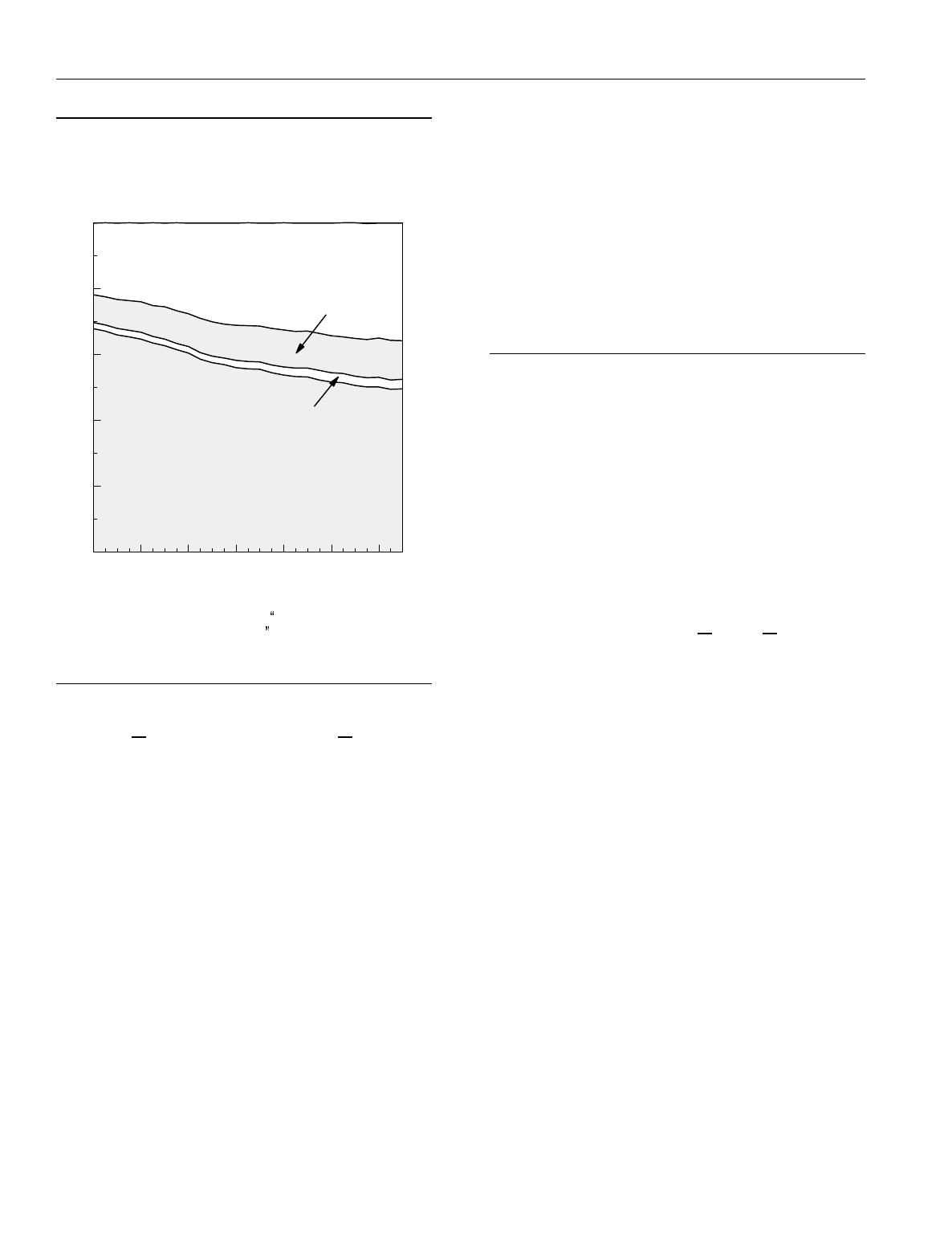

Figure 1.

The Conflict Among Goals of Income Taxation

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office, derived from Treasury Department, Office of Tax Analysis,

Federal Income Tax Treatment of Married and

Single Taxpayers

(September 13, 1977), p. 2.

4 FOR BETTR OR FOR WORSE: MARRIAGE AND THE FEDERAL INCOME TAX June 1997

Box 1.

A Marriage Penalty

A couple with $75,000 in total earnings, split evenly

between the husband and the wife, would have incurred

a marriage penalty of nearly $1,400 under 1996 tax law.

The penalty results from two factors. First, the com-

bined standard deduction for two individual tax filers

would have been $8,000

$1,300 more than the stan-

dard deduction available on a joint return. At the cou-

ple's marginal tax rate of 28 percent, the lower deduc-

tion would have increased the couple's tax liability by

$364 (28 percent of $1,300). Second, because tax

brackets for joint returns were less than twice as wide as

those for individual returns, $7,900 that is taxed at 15

percent on individual returns would have incurred a 28

percent rate on a joint return. That higher tax rate

would have raised the couple's tax liability by an addi-

tional $1,027 (28 percent minus 15 percent equals 13

percent of $7,900). In combination, the two factors

would have increased the couple's tax liability by 1.9

percent of their adjusted gross income.

Husband

Wife Couple

Adjusted Gross Income $37,500 $37,500 $75,000

Less personal exemptions 2,550 2,550 5,100

Less standard deduction 4,000 4,000 6,700

Equals taxable income 30,950 30,950 63,200

Taxable at 15 percent 24,000 24,000 40,100

Taxable at 28 percent 6,950 6,950 23,100

Tax Liability 5,546 5,546 12,483

Marriage Penalty $1,391

As a Percentage of Adjusted Gross Income 1.9

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office.

of married couples. Alternatively, married couples with

equal incomes but unequal division of income between

spouses could pay different taxes based on the principle

that the division of income within couples measures

different abilities to pay. Or, as in the United States,

the taxes of a married couple could depend only on their

total income, thus satisfying the goal of equal treatment

of married couples but sacrificing the goal of marriage

neutrality because some married couples would pay

higher or lower taxes than they would if they were sin-

gle. In practice, the last solution to the contradiction

among the three goals can impose a marriage penalty

(that is, higher taxes than if they were not married) on

some couples while granting a marriage bonus (lower

taxes) to others. Two examples based on the federal

individual income tax demonstrate these possibilities.

Example: A Marriage Penalty

. A married couple

with $75,000 in earnings, split evenly between husband

and wife, paid $1,391 more in federal individual in-

come taxes in 1996 than they would have if they had

not been married (see Box 1). Two factors contribute

to that marriage penalty. First, when filing a joint tax

return, the couple can claim a standard deduction that is

$1,300 less than the two single standard deductions

$4,000 each they would receive if they were not mar-

ried. At a marginal tax rate of 28 percent, the smaller

deduction costs them $364 (28 percent of $1,300) in

additional taxes. Second, because tax brackets for mar-

ried couples are not twice as wide as those for single

tax filers, $7,900 that is taxed at 15 percent on the two

single returns faces a 28 percent rate on the joint return,

yielding an additional tax of $1,027 (28 percent minus

CHAPTER ONE MARRIAGE PENALTIES AND BONUSES 5

Box 2.

A Marriage Bonus

A couple with $75,000 in total earnings, all earned by

the wife, would have received a marriage bonus of

nearly $4,000 under 1996 tax law. The bonus results

from three factors. First, filing jointly, the couple would

have claimed $5,100 in personal exemptions, twice

what they could have claimed on two single returns. At

a 31 percent tax rate, the larger exemption would have

reduced the couple's tax liability by $791 (31 percent of

$2,550). Second, the standard deduction of $6,700 on a

joint return would have been $2,700 more than the

$4,000 standard deduction the wife could have claimed

on an individual return. (The husband, filing individu-

ally with no income, could not take the deduction.) At

the couple's marginal tax rate of 31 percent, the larger

deduction would have reduced the couple's tax liability

by $837 (31 percent of $2,700). Finally, because tax

brackets for joint returns were wider than those for indi-

vidual returns, $16,100 that is taxed at 28 percent on

individual returns would have been taxed at only 15 per-

cent on a joint return and $5,050 taxed at 31 percent

rather than at 28 percent. Those lower tax rates would

have reduced the couple's tax liability by an additional

$2,245 (28 percent minus 15 percent equals 13 percent

of $16,100 plus 31 percent minus 28 percent equals 3

percent of $5,050). In combination, the three factors

would have lowered the couple's tax liability by 5.2 per-

cent of their adjusted gross income.

Husband

Wife Couple

Adjusted Gross Income $0 $75,000 $75,000

Less personal exemptions 2,550 2,550 5,100

Less standard deduction 4,000 4,000 6,700

Equals taxable income 0 68,450 63,200

Taxable at 15 percent 0 24,000 40,100

Taxable at 28 percent 0 34,150 23,100

Taxable at 31 percent 0 10,300 0

Tax Liability 0 16,355 12,483

Marriage Bonus $3,872

As a Percentage of Adjusted Gross Income 5.2

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office.

15 percent equals 13 percent of $7,900). In combina-

tion, the two factors generate a marriage penalty of

$1,391 in higher taxes. Because the couple receives the

full value of personal exemptions whether or not they

are married, exemptions cannot contribute to their mar-

riage penalty.

Example: A Marriage Bonus

. The couple described

in the preceding example would have received a mar-

riage bonus of more than $3,500 in 1996 if all of the

couple's income were earned by one spouse

the wife in

this instance (see Box 2). Three factors generate the

bonus. First, because the husband has no earnings, he

would receive no benefit from the personal exemption

when filing as a single person. Filing jointly, the couple

thus receives an additional $2,550 exemption, worth

$791 in lower taxes (31 percent of $2,550). Second,

the married couple can claim a standard deduction that

is $2,700 greater than that which they can claim as sin-

gle filers

again because the husband, without earnings,

receives no value from the deduction as a single filer.

The additional standard deduction lowers the couple's

6 FOR BETTR OR FOR WORSE: MARRIAGE AND THE FEDERAL INCOME TAX June 1997

taxes by $837 (31 percent of $2,700). Finally, because

tax brackets for joint filers are wider than those for sin-

gle people, $16,100 more of the couple's income is

taxed at 15 percent rather than 28 percent, yielding tax

savings of $2,093 (28 percent minus 15 percent equals

13 percent of $16,100), and $5,050 is taxed at 28 per-

cent rather than 31 percent, saving another $152 (31

percent minus 28 percent equals 3 percent of $5,050).

The three factors combine to provide the couple with a

marriage bonus of $3,872 in lower taxes.

A Histor

y

of the Treatment

of Married Cou

p

les in the

Federal Income Tax

Since its inception in 1913, the federal individual in-

come tax has been periodically adjusted in its treatment

of married couples. Until 1948, the government for-

mally imposed income taxes on individuals, but couples

were allowed to file joint returns as early as 1918, even

though joint returns used the same schedules as individ-

ual returns. Individual taxation meant that marital sta-

2

tus had no effect on taxes and, as a result, married cou-

ples with identical total incomes could pay quite differ-

ent taxes, depending on the division of income between

husband and wife.

Community Property Laws

Community property laws in some states complicated

the situation by requiring that husbands and wives

share all of their income equally. The laws therefore

provided a basis for each spouse to pay federal income

taxes on one-half of the couple's income. That claim

equalized taxes for couples with the same income, but

created a situation in which some couples

those in

which husband and wife had different earnings re-

ceived a marriage bonus, paying lower taxes after mar-

riage than before. In 1930, the Supreme Court vali-

dated the splitting of income in community property

states [

Poe v. Seaborn

, 282 U.S. 101 (1930)], but de-

nied that opportunity to couples in other states, even if

they agreed by contract to share their incomes equally

[

Lucas v. Earl

, 281 U.S. 111 (1930)].

The distinction drawn between couples in states

that have community property laws and those that have

common property laws meant that couples with identi-

cal incomes could pay higher federal taxes in the latter

states than in the former. Because only a small fraction

of the population paid any income taxes before World

War II fewer than 4 million people owed any tax in

1939 the Congress felt little pressure to change this

situation during the 1930s. In fact, before 1948, the

Congress's only effort to change the filing status of cou-

ples came in 1941 in a proposal to require couples to

file joint returns at individual rates. The proposal failed

when opponents objected that the change would raise

the taxes paid by virtually all two-earner couples.

As income taxes increasingly became a means to

finance the war effort in the 1940s between 1939 and

1945, taxable returns increased more than tenfold to

nearly 43 million state governments more widely real-

ized that their citizens would pay lower federal taxes if

the states adopted community property laws. After fail-

ing to satisfy a skeptical Supreme Court with optional

community property laws [

Commissioner v. Harmon

,

323 U.S. 44 (1944)], Oklahoma and Oregon enacted

mandatory community property rules that met the

court's objections, even though couples were allowed to

opt out of their coverage. Other states quickly followed

suit. Concerns about problems that community prop-

erty laws could create in nontax areas brought pressure

on the Congress to act on the issue.

Joint Returns

The Congress responded in 1948 by allowing all mar-

ried couples to file joint returns and pay taxes on their

total income using schedules that had brackets twice the

width of those for single individuals. That approach

effectively assigned each spouse one-half of the cou-

2. This history of the treatment of couples in the federal individual in-

come tax draws from Boris I. Bittker, "Federal Income Taxation and

the Family,"

Stanford Law Review

, vol. 27 (July 1975), pp. 1389-

1463; June O'Neill, "Family Issues in Taxation," Rudy Penner, ed.,

Taxing the Family

(Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute,

1983), pp. 1-22; Edward J. McCaffery, "Taxation and the Family: A

Fresh Look at Behavioral Gender Biases in the Code,"

UCLA Law

Review

, vol. 40 (April 1993), pp. 983-1060; Harvey S. Rosen, "The

Marriage Tax Is Down But Not Out,"

National Tax Journal

, vol. XL,

no. 4 (December 1987), pp. 567-575; and Gregg A. Esenwein,

Mar-

riage Tax Penalties and Bonuses Under the Federal Income Tax

,

CRS Report for Congress 93-475E (Congressional Research Service,

May 7, 1993).

CHAPTER ONE MARRIAGE PENALTIES AND BONUSES 7

ple's income and meant that a couple paid taxes equal

to twice what a single person would pay if he earned

one-half of the couple's total income. As a result, a sin-

gle taxpayer would pay higher taxes than a married

couple with the same total income. In effect, the new

law provided a marriage bonus for most couples, and

eliminated neutrality of tax laws with respect to mar-

riage. Under the new law, marriage would leave tax

liabilities unchanged only for couples who had no tax

liability or in instances in which husband and wife had

identical earnings.

In 1951, the Congress extended some of the advan-

tage that married taxpayers received from income-split-

ting to unmarried taxpayers supporting dependents by

establishing new schedules for "heads of household."

Taxpayers in this new category incurred tax liability

that was less than that of single taxpayers but greater

than that of married couples with the same total in-

come. The head-of-household filing status reduced

marriage bonuses for couples with children by lowering

the tax liabilities of single parents.

Although creating the joint filing status eliminated

the unequal treatment of married couples in different

states, it created sizable differences in the taxes paid by

single and married people. Predictably, unmarried peo-

ple viewed those differences as a tax on singles rather

than as a bonus for couples, an effect magnified by the

high marginal tax rates paid by upper-income taxpay-

ers. Under 1970 rates, for example, a single person

earning $20,000 paid $5,328 in income taxes, 42 per-

cent more than the $3,750 paid by a married couple

with the same total income. (About 15 percent of the

difference resulted from the two personal exemptions

allowed the married couple, whereas the single taxpayer

was allowed only one. The rest of the difference de-

rived from higher tax rates for single taxpayers.)

The Tax Reform Act of 1969 partially remedied the

disparity by limiting the tax liability of single people to

no more than 20 percent above that of married couples

with the same taxable income, effective for tax years

after 1970. For example, the change reduced the dis-

parity in taxes between a single taxpayer and a married

couple, each with $20,000 in total income, from 42 per-

cent to 24 percent. But the limitation created marriage

penalties for couples in which husband and wife had

similar incomes and left in place marriage bonuses

when the earnings split between spouses was less equal.

The Earned Income Tax Credit

The Tax Reform Act of 1975 created the Earned In-

come Tax Credit (EITC), a refundable credit available

to low-income taxpayers with earnings. Because indi-

vidual and joint filers have the same restrictions on

their incomes for receiving the credit, the EITC added a

potential penalty on married couples. If a low-income

person who qualified for the EITC got married, the

combined income of the couple could make them ineli-

gible for the credit. At the same time, the requirement

that credit claimants have a dependent child meant that

couples could receive a tax bonus if a low-earner mar-

ried a single parent with no earnings. The magnitude of

both marriage penalties and bonuses resulting from the

EITC was increased by subsequent tax acts that created

different credits for taxpayers with one and more than

one child, raised the maximum value of the credit, and

extended eligibility to childless families.

Recent Changes in Tax Law

Complaints from two-earner couples about the "mar-

riage tax" they had to pay led the Congress to reduce

the taxes for those couples as part of the Economic Re-

covery Tax Act of 1981. That act established a two-

earner deduction equal to 10 percent of the earnings of

the lower-earning spouse, up to a maximum deduction

of $3,000. The deduction reduced the marriage penalty

for all couples facing the penalty, and eliminated the

penalty entirely for some, but increased the size of the

marriage bonus for others. Even with the new deduc-

tion, however, some couples paid more than $4,000 in

added taxes because they filed joint returns.

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 repealed the two-

earner deduction as part of a broad reform that in-

creased the standard deduction for married couples and

collapsed the tax schedule from 15 brackets with a

maximum rate of 50 percent to just two brackets with a

maximum rate of 28 percent. (Married couples with

taxable income between $71,900 and $149,250 faced

tax rates of 33 percent as the act phased out the bene-

fits of the 15 percent bracket over that income range.

The 33 percent rate was further extended up to tax-

able income of $192,930 for a family of four by phas-

ing out the benefits from personal exemptions.) In

combination, those changes sharply reduced the mar-

riage penalty. For example, the act cut the marriage

8 FOR BETTR OR FOR WORSE: MARRIAGE AND THE FEDERAL INCOME TAX June 1997

penalty for a couple in which the husband and wife each

earned $50,000 by more than one-half in 1988, from

$2,609 to $1,284. Although the act did not eliminate

3

marriage penalties and bonuses, it reduced them enough

to quiet most critics.

Tax increases in 1990 and 1993 expanded the num-

ber of tax brackets from two to five, raised the maxi-

mum marginal tax rate to 39.6 percent, and sharply in-

creased the size and coverage of the earned income tax

credit. In combination, those changes imposed signifi-

cantly larger marriage penalties on both low- and high-

income families, and increased the size of the marriage

bonus for some couples. For example, a childless cou-

ple in which husband and wife each earned $300,000

faced a marriage penalty of nearly $16,000 after the

1993 act, compared with a penalty of about $1,900 un-

der the old law. At the other end of the income scale, a

4

one-earner couple with two children and earnings of

$10,000 saw their marriage penalty of $161 turn into a

bonus of nearly $500.

Those increases in the disparity between the taxes

paid by married couples and their unmarried counter-

parts have revived interest in reducing the effects of

marriage on tax liability. The "Contract with America

Tax Relief Act of 1995," as passed by the House of

Representatives, would have reduced marriage penalties

slightly by giving tax credits to couples incurring penal-

ties. To constrain the revenue losses from the provi-

sion, the act would have limited credits to $145. Given

that the penalty, under one broad measure, averages

nearly $1,400 for couples who incur it and can exceed

$20,000 for high-income couples, the credit would have

done little to offset the tax costs of marriage. The Sen-

ate in 1995 considered a proposal to set the standard

deduction for joint filers equal to twice that for single

filers. The change would have been phased in over a

10-year period. That proposal would have reduced or

eliminated penalties for taxpayers who do not itemize

their deductions. At the same time, it would have in-

creased bonuses for many couples and had no effect on

penalties for couples who continued to itemize deduc-

tions. The Balanced Budget Act of 1995, which in-

cluded the Senate provision, was vetoed by President

Clinton.

The United States is among a minority of devel-

oped nations that tax married couples. More than two-

thirds of the countries that are members of the Organi-

zation for Economic Cooperation and Development

(OECD) tax married couples as individuals. Only three

other developed countries tax couples jointly as does

the United States, and four others tax all family mem-

bers as a single entity (see Appendix A). Furthermore,

the trend has been moving away from joint taxation:

over the last two decades, 10 OECD members switched

from joint to individual taxation of married couples.

During the same period, no member country changed in

the other direction.

States vary more widely in taxing the incomes of

married couples (see Appendix B). Of the 42 states

that tax incomes, only 12 tax couples in ways that gen-

erate significant marriage penalties. Another 15 states

tax couples jointly, but use rate schedules that substan-

tially reduce or eliminate penalties. Nine states and the

District of Columbia allow couples to file individually

on a single return, thus providing them with tax savings

available to unmarried taxpayers. Finally, six states

impose a single tax rate that, in combination with stan-

dard deductions and exemptions, precludes all marriage

penalties.

The history of the changing taxation of couples and

single people demonstrates the tension between impos-

ing higher taxes on one group or the other with a pro-

gressive rate structure. Taxing individuals, as was the

case when the income tax began, avoids the problem of

different taxes based on marital status but runs afoul of

the principle of taxing married couples equally and of

state community property laws. The 1948 "solution" of

joint taxation dealt with both of those problems but

necessarily imposed higher taxes on single people in

relation to married couples, thus violating the principle

of marriage neutrality. The last five decades have wit-

nessed periodic movements between those two poles,

depending on the demands for fairness toward singles

or couples. As long as the Congress pursues the three

mutually incompatible goals of marriage neutrality,

equal treatment of couples with similar incomes, and

progressive tax rates, the tension between the two posi-

tions will continue.

3. Joint Committee on Taxation,

General Explanation of the Tax Re-

form Act of 1986

, Joint Committee Print JCS-10-87 (May 4, 1987),

p. 19.

4. Daniel R. Feenberg and Harvey S. Rosen, "Recent Developments in

the Marriage Tax,"

National Tax Journal

, vol. 47, no. 1 (March

1995), p. 94.

CHAPTER ONE MARRIAGE PENALTIES AND BONUSES 9

The Si

g

nificance of Marria

g

e

Penalties and Bonuses

Does it matter that marriage penalties and bonuses arise

from a tax code designed to meet the goals of equal tax

liabilities for married couples with the same incomes

and progressive taxation? Three issues are paramount

in answering that question: the fairness of tax levies

among couples, the effects of taxes on how much peo-

ple choose to work, and the effects of taxes on marriage

and divorce.

Fairness

Equal treatment under the law is a basic concept of fair-

ness. Horizontal equity in taxation stipulates that peo-

ple who have equal ability to pay receive equal treat-

ment and therefore bear the same tax burden. Al-

though determining ability to pay may be difficult in

practice, the concept of horizontal equity helps in eval-

uating the conflicting goals of the tax system that lead

to marriage penalties and bonuses. On the one hand, if

the act of marriage has no effect on a couple's ability to

pay, horizontal equity implies that taxes be marriage

neutral

that is, that couples pay the same taxes

whether or not they are married. On the other hand, if

they are otherwise similar, married couples with the

same total income must pay the same taxes to satisfy

the criterion of equity. In the face of progressive tax

rates, however, the two goals conflict (see "Defining

Marriage Penalties and Bonuses" above). Reconciling

them demands investigation of marriage penalties and

bonuses.

One issue that must precede the question of hori-

zontal equity involves the appropriate unit on which to

levy taxes. If individuals provide their own resources

and do not share with others, the most appropriate unit

would be the individual. If, however, people share re-

sources and consume goods and services in groups,

those groups are the appropriate units for the purpose

of taxation. The federal income tax code assumes that

married couples combine their incomes and other re-

sources to support themselves and their dependents,

and therefore imposes taxes on the joint incomes of

spouses. The code stops short of defining all tax units

on the basis of shared incomes. On the one hand, mar-

ried couples are presumed to combine resources and

thus must file jointly. On the other hand, people in re-

lationships not based on legal marriage or other family

relationships must pay taxes on their separate incomes,

even if they consume together. Unmarried couples or

two members of the same family sharing a home are

taxed as individuals.

Despite the implicit assumptions built into the tax

code, marriage may or may not affect a couple's ability

to pay, depending on whether the couple's costs of liv-

ing change. If the couple lived together before mar-

riage, simply getting married would have little or no

effect on their costs and hence on their ability to pay. If

they create a new household after marriage, their costs

could rise or fall. If, for example, each person lived

with his or her parents before the wedding, marriage

could increase their costs, but if each had maintained a

separate household, combining those households into

one could reduce costs. Because living arrangements

before and after marriage need not differ, the tax sys-

tem might logically assume that marriage has no intrin-

sic effect on a couple's ability to pay and therefore that

marriage neutrality would be desirable. The conclusion

that marriage should not affect a couple's tax bill says

nothing about the fairness of taxation of either married

or unmarried couples.

Whether imposing the same taxes on married cou-

ples with equal incomes satisfies the principle of hori-

zontal equity is more problematic. Two childless cou-

ples who have the same total income, earned in each

case by two full-time workers, may also have the same

ability to pay, regardless of the division of income be-

tween spouses. If one couple had only one worker,

however, the couples would have quite different abili-

ties to pay because the nonworking spouse could pro-

vide services in kind that are not as readily available to

the two-earner couple. But if the working spouse of the

one-earner couple held two different jobs, the couple's

ability to pay would be different yet. In essence, as is

more generally true, income alone provides a poor mea-

sure of ability to pay. Requiring that married couples

with a given amount of total income pay the same taxes

may therefore not satisfy the principle of horizontal

equity.

Children complicate the issue. Tax rules can be

totally indifferent to the presence of children, treating

the decision to have and rear children as entirely the

10 FOR BETTR OR FOR WORSE: MARRIAGE AND THE FEDERAL INCOME TAX June 1997

responsibility of the parents. If, however, society val-

ues children and chooses to subsidize parents who rear

them, tax rules, as in the current tax code, may be used

to provide tax relief to families with children. Further-

more, the government may wish to encourage couples

to have children by not taxing any resources that are

provided by parents who stay home to care for them.

Under that assumption, equal taxation of one- and two-

earner couples who have the same total incomes may be

appropriate.

The movement of people through a variety of tax

statuses during their lifetimes and their consequent lia-

bility for different amounts of tax over time further

complicate issues of fairness. A couple may change

from being two unmarried individuals with earnings, to

a two-earner childless married couple, to a one-earner

couple with one spouse caring for children, to a two-

earner couple purchasing child care, to a two-earner

couple with older children who can care for themselves,

and back to a two-earner childless couple. The individ-

ual income tax would treat the couple differently in

each period, whether or not their ability to pay changes.

Depending on the division of earnings between spouses,

the couple may pay higher or lower taxes because they

are married, even if they experience no change in ability

to pay. The various features of the tax code affect peo-

ple differently throughout their lives, sometimes reduc-

ing their tax liability and other times increasing it. As-

sessing whether they are taxed fairly depends on

whether their situation is considered in any given year

or over their entire lifetime as a couple. What may ap-

pear to be unfair in one year may appear quite different

when viewed in a lifetime context.

The conflict between the two goals of marriage

neutrality and taxing couples with equal incomes the

same would matter little if the marital penalties and

bonuses generated were small. To determine the impor-

tance of those effects in terms of both their size and

the number of couples affected requires a close exami-

nation of who pays the penalties and who receives the

bonuses.

Effects on the Supply of Labor

Taxing married couples may significantly affect the

amount of paid work done by the second worker in each

couple because a husband's and wife's incomes are

combined to determine tax liability. For example, if a

5

man earns $75,000 and his wife decides to take a job,

the couple will pay 28 percent of the wife's earnings to

the federal government as income taxes, a further 15.3

percent in Social Security taxes (counting both em-

ployer and employee shares), and, possibly, a state or

local income tax. Because the husband's income has

6

already moved the couple into the 28 percent income

tax bracket, the first dollar of the wife's income bears a

total tax rate greater than 43 percent. If she was single,

the wife would pay no income tax on the first $6,550

that she earned and only a 15 percent income tax on the