Global Development And Environment Institute

Tufts University

Medford, MA 02155

http://ase.tufts.edu/gdae

A GDAE Teaching Module on Social and Environmental Issues in Economics

By Brian Roach, Neva Goodwin, and Julie Nelson

Consumption and the

Consumer Society

This reading is based on portions of Chapter 8 from: Microeconomics in Context, Fourth Edition.

Copyright Routledge, 2019.

Copyright © 2019 Global Development And Environment Institute, Tufts University.

Reproduced by permission. Copyright release is hereby granted for instructors to copy this

module for instructional purposes.

Students may also download the reading directly from https://ase.tufts.edu/gdae

Comments and feedback from course use are welcomed:

Comments and feedback from course use are welcomed:

Global Development And Environment Institute

Tufts University

Somerville, MA 02144

http://ase.tufts.edu/gdae

E-mail: [email protected]

NOTE – terms denoted in bold face are defined in the KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS section at the

end of the module.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 5

2. ECONOMIC THEORY AND CONSUMPTION ............................................... 5

2.1 Consumer Sovereignty .............................................................................................. 5

2.2 The Budget Line ....................................................................................................... 6

2.3 Consumer Utility ....................................................................................................... 9

2.4 Limitations of the Standard Consumer Model ........................................................ 11

3. CONSUMPTION IN HISTORICAL & INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT .... 13

3.1 A Brief History of Consumer Society ..................................................................... 13

3.2 Limits to Modern Consumerism ............................................................................. 16

Insufficient Consumption: Poverty .......................................................................... 16

Nonconsumerist Values ........................................................................................... 17

4. CONSUMPTION IN A SOCIAL CONTEXT .................................................. 18

4.1 Social Comparisons ................................................................................................ 18

4.2 Advertising .............................................................................................................. 20

4.3 Private Versus Public Consumption ....................................................................... 22

5. CONSUMPTION IN AN ENVIRONMENTAL CONTEXT .......................... 23

5.1 The Link Between Consumption and the Environment .......................................... 24

5.2 Green Consumerism ................................................................................................ 26

6. CONSUMPTION AND WELL-BEING ............................................................ 26

6.1 Does Money Buy Happiness? ................................................................................. 27

6.2 Affluenza and Voluntary Simplicity ....................................................................... 30

6.3 Consumption and Public Policy .............................................................................. 32

Flexible Work Hours ............................................................................................... 33

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

4

Advertising Regulations ........................................................................................... 33

Consumption Taxation ............................................................................................. 34

KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS ............................................................................... 36

REFERENCES .......................................................................................................... 38

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS ...................................................................................... 41

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

5

1. INTRODUCTION

The economic activity of consumption is defined as the process by which goods and services are

put to final use by people. But this rather dry, academic definition fails to capture the multifaceted

role of consumerism in our lives. As one researcher put it:

For a start, it is immediately clear that consumption goes way beyond just satisfying

physical or physiological needs for food, shelter, and so on. Material goods are

deeply implicated in individuals’ psychological and social lives. People create and

maintain identities using material things… The “evocative power” of material

things facilitates a range of complex, deeply ingrained “social conversations” about

status, identity, social cohesion, and the pursuit of personal and cultural meaning.

1

Until recently, most economists paid little attention to the motivations behind consumer behavior.

Economic theory in the twentieth century simply assumed that the vast majority of people act

rationally to maximize their utility. But as suggested in the quotation above, perhaps no other

economic activity is shaped by its social context more than consumption. Our consumption

behavior conveys a message to ourselves and others about who we are and how we fit in with, or

separate ourselves from, other people.

Modern consumption must also be placed in a historical context. When can we say that “consumer

society” originated? Furthermore, is consumerism as experienced in the United States and other

countries something that is ingrained in us by evolution, or is it something that has been created

by marketing and other social and political forces?

Finally, it is impossible to present a comprehensive analysis of consumption without considering

its environmental context. Specifically, ecological research suggests that consumption levels in the

United States and many other developed countries have reached unsustainable levels. According

to one recent analysis, if everyone in the world had the same living standard as the average

American, we would need at least four earths to supply enough resources and process all the

waste.

2

So any serious discussion of sustainability must consider the future of consumption

patterns throughout the world.

2. Economic Theory and Consumption

2.1 Consumer Sovereignty

Before focusing on the historical, social, and environmental contexts of consumption, we present

the neoclassical economic theory on the topic. The neoclassical model is based on overly simplistic

assumptions about human behavior, but it still provides a useful basis for thinking about

consumption decisions.

1

Jackson, 2008, p. 49.

2

McDonald, 2015.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

6

Adam Smith once said, “Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production and the welfare

of the producer ought to be attended to, only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of

the consumer.”

3

The belief that satisfaction of consumers’ needs and wants is the ultimate

economic goal and that the economy is fundamentally ruled by consumer desires is called

consumer sovereignty. Consumer sovereignty suggests that all economic production is ultimately

driven by the preferences of consumers. For example, consider the fact that sales of sport utility

vehicles (SUVs) in the United States have been increasing in recent years, while sales of small

cars and sedans have declined.

4

The theory of consumer sovereignty would suggest that the

primary reason for the growth of SUV sales is that consumers prefer larger vehicles over cars. We

would argue that a change in consumers’ tastes and preferences increased the demand for SUVs

and decreased the demand for cars. The possibility that the shift in demand was driven primarily

by automakers’ marketing efforts to sell large vehicles with higher profit margins would not be

consistent with consumer sovereignty.

The notion of consumer sovereignty has both positive and normative components. From a positive

perspective, we can consider whether consumers really do “drive the economy.” Since consumers

can be swayed by advertising, we will consider the impact of advertising in more detail later in

this module.

Consumer sovereignty can also be viewed from a normative perspective. Should people’s

preferences, as consumers, drive all decisions about economic production, distribution, and

resource management? People are more than just consumers. Consumption activities most directly

address living standard (or lifestyle) goals, which have to do with satisfying basic needs and

getting pleasure through the use of goods and services.

But people are often interested in other goals, such as self-realization, fairness, freedom,

participation, social relations, and ecological balance. To some extent, these goals may be attained

through consumption, but often they conflict with their goals as consumers. Many people also

obtain intrinsic satisfaction from working and producing. Work can create and maintain

relationships. It can be a basis for self-respect and a significant part of what gives life purpose and

meaning.

If the economy is to promote well-being, all these goals must be taken into account. An economy

that made people moderately happy as consumers but absolutely miserable as workers, citizens, or

community members could hardly be considered a rousing success. We evaluate the relationship

between consumption and well-being further toward the end of this module. But first we turn to

the formal neoclassical theory on consumption.

2.2 The Budget Line

The choices that we make as consumers illustrate yet another example of economic tradeoffs. In

this case, consumers are constrained in their spending by the amount of their total budget. We can

represent this in a simple model in which consumers have only two goods from which to choose.

3

Smith, 1930, p. 625.

4

Bomey, 2017.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

7

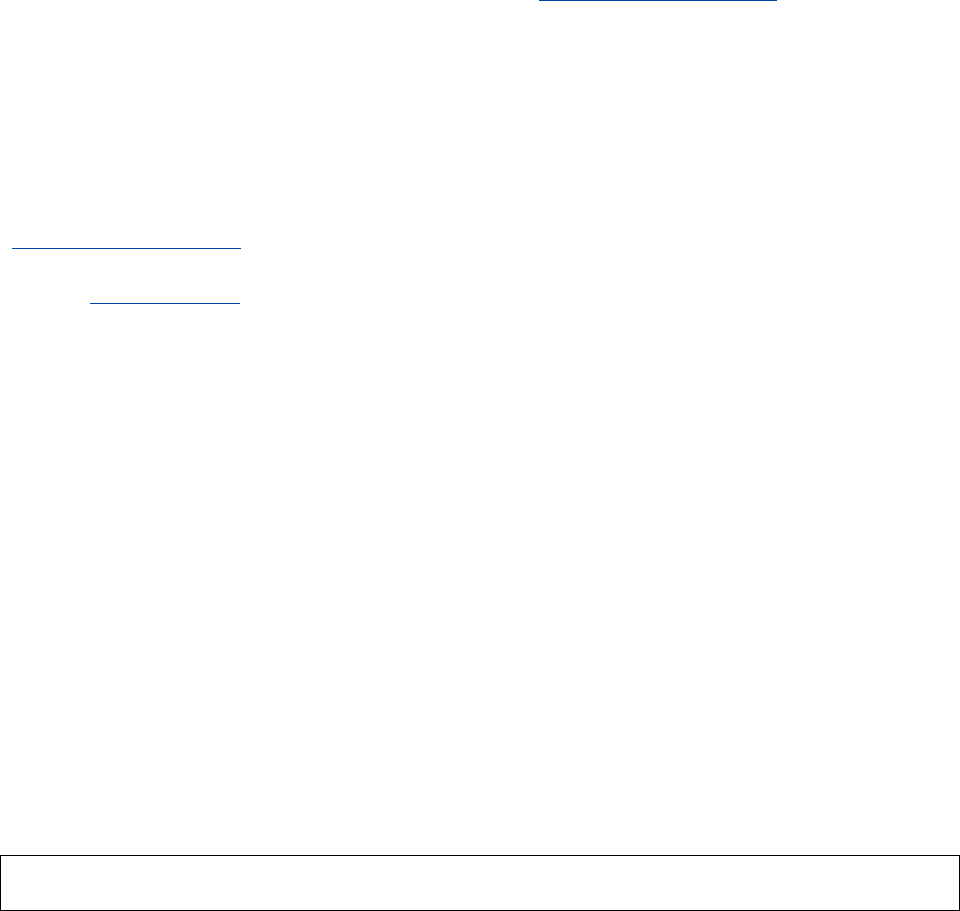

In Figure 1, we present a budget line, which shows the combinations of two goods that a consumer

can purchase. In this example, our consumer—let’s call him Quong—has a budget of $8. The two

goods that are available for him to purchase are chocolate bars and bags of nuts. The price of

chocolate bars is $1 each, and nuts sell for $2 per bag.

Figure 1. The Budget Line

If Quong spends his $8 only on chocolate, he can buy 8 bars, as indicated by the point where the

budget line touches the vertical axis. If he buys only nuts, he can buy 4 bags, as indicated by the

(4, 0) point on the horizontal axis. He can also buy any combination in between. For example, the

point (2, 4), which indicates 2 bags of nuts and 4 chocolate bars, is also achievable. This is because

(2 Å~ $2) + (4 Å~ $1) = $8. (We draw the budget line as continuous to reflect the more general

case that might apply when there are many more alternatives, although here we assume that Quong

buys only whole bars and whole bags, not fractions of them.)

A budget line is similar to the concept of a production-possibilities frontier. A budget line defines

the choices that are possible for Quong. Points above and to the right of the budget line are not

affordable. Points below and to the left of the budget line are affordable but do not use up the total

budget. In this simple model, economists assume that people always want more of at least one of

the goods in question. Consuming below the budget line would therefore be inefficient; funds that

could be used to satisfy Quong’s desires are being left unused. Therefore, economists assume that

consumers will choose to consume at a point on the budget line.

The position of the budget line depends on the size of the total budget (income) and on the prices

of the two goods. For example, if Quong has $10 to spend, instead of $8, the line would shift

outward in a parallel manner, as shown in Figure 2. He could now consume more nuts, or more

chocolate, or a more generous combination of both.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

8

Figure 2. Effect of an Increase in Income

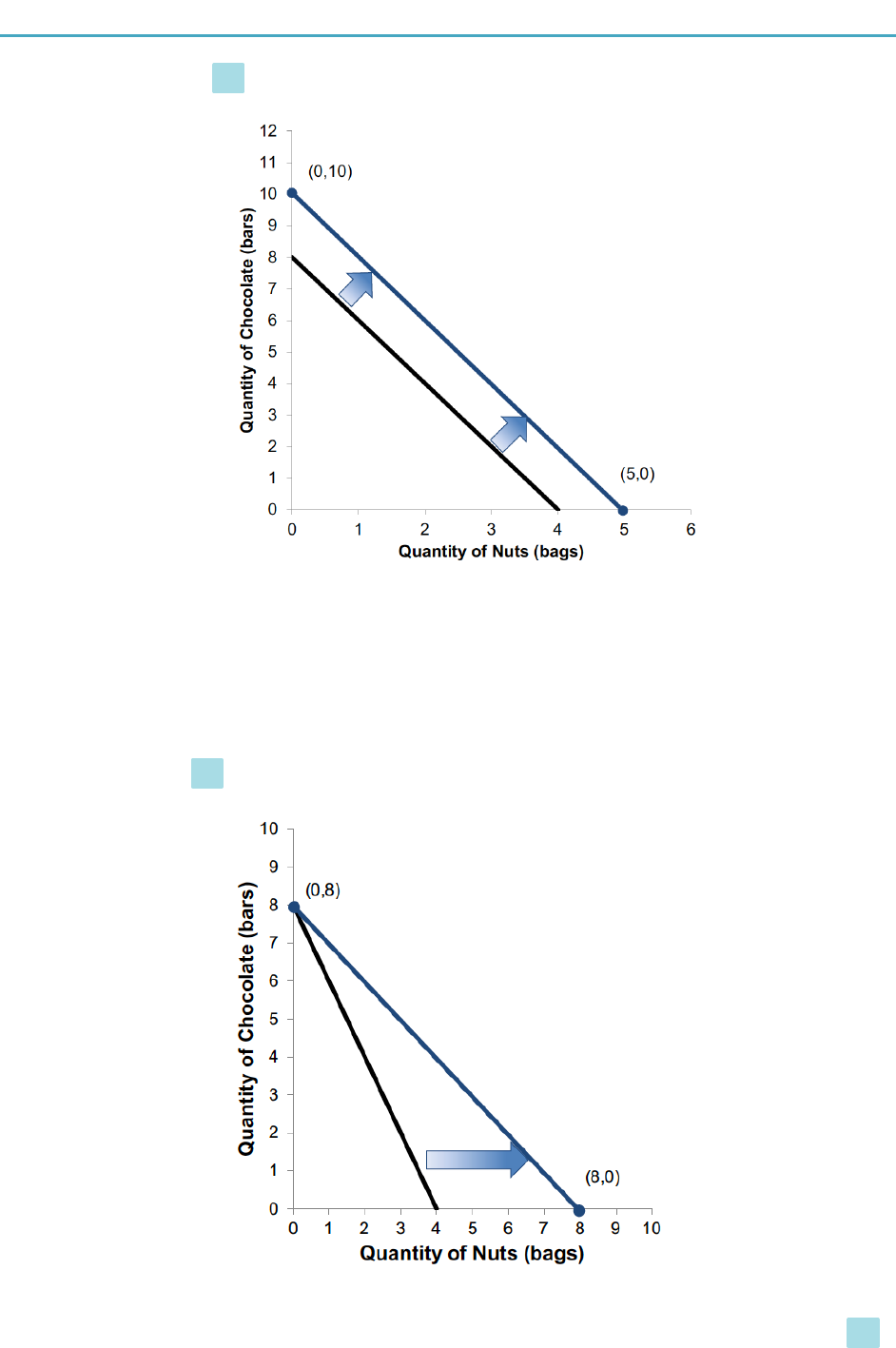

A change in the price of one of the goods will cause the budget line to rotate around a point on one

of the axes. So if the price of nuts dropped to $1 per bag (and Quong’s income was again $8), the

budget line would rotate out, as shown in Figure 3. Now, if Quong bought only nuts, he could buy

8 bags instead of 4. With the price of chocolate unchanged, however, he still could not buy more

than 8 chocolate bars.

Figure 3. Effect of a Fall in the Price of One Good

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

9

Note that if both prices change, the budget line could shift in any direction, depending on how the

two prices changed. If both prices changed by the same percentage, then the new budget line would

be parallel to the original, similar to a change in income. Draw some graphs to prove this to

yourself.

A budget line tells us what combinations of purchases are possible, but it does not tell us which

combination a consumer will choose. To get to this, we must add the theory of utility.

2.3 Consumer Utility

Economists have traditionally defined consumers’ “problem” as how to maximize utility given

their income constraints. Utility is a somewhat vague concept. However, although economists

attempt to measure welfare quantitatively, utility is generally recognized as something that cannot

be measured quantitatively and cannot be aggregated across individuals.

5

We define utility as the

pleasure or satisfaction that individuals receive from consuming goods, services, or experiences.

Furthermore, we assume that individuals make consumer decisions to increase their utility. But,

we recognize that consumers often do not always make the best decisions, because they sometimes

act irrationally or are unduly influenced by certain information (or misinformation). We discuss

the implications of this further in the next section.

Economists have developed a neoclassical model of utility that, like many economic models, is an

abstraction from reality that is useful for illustrating a particular concept. So despite the fact that

we just said that utility cannot be measured quantitatively in the real world, for the purposes of our

model we assume that we actually can measure utility in some imaginary units of “satisfaction.”

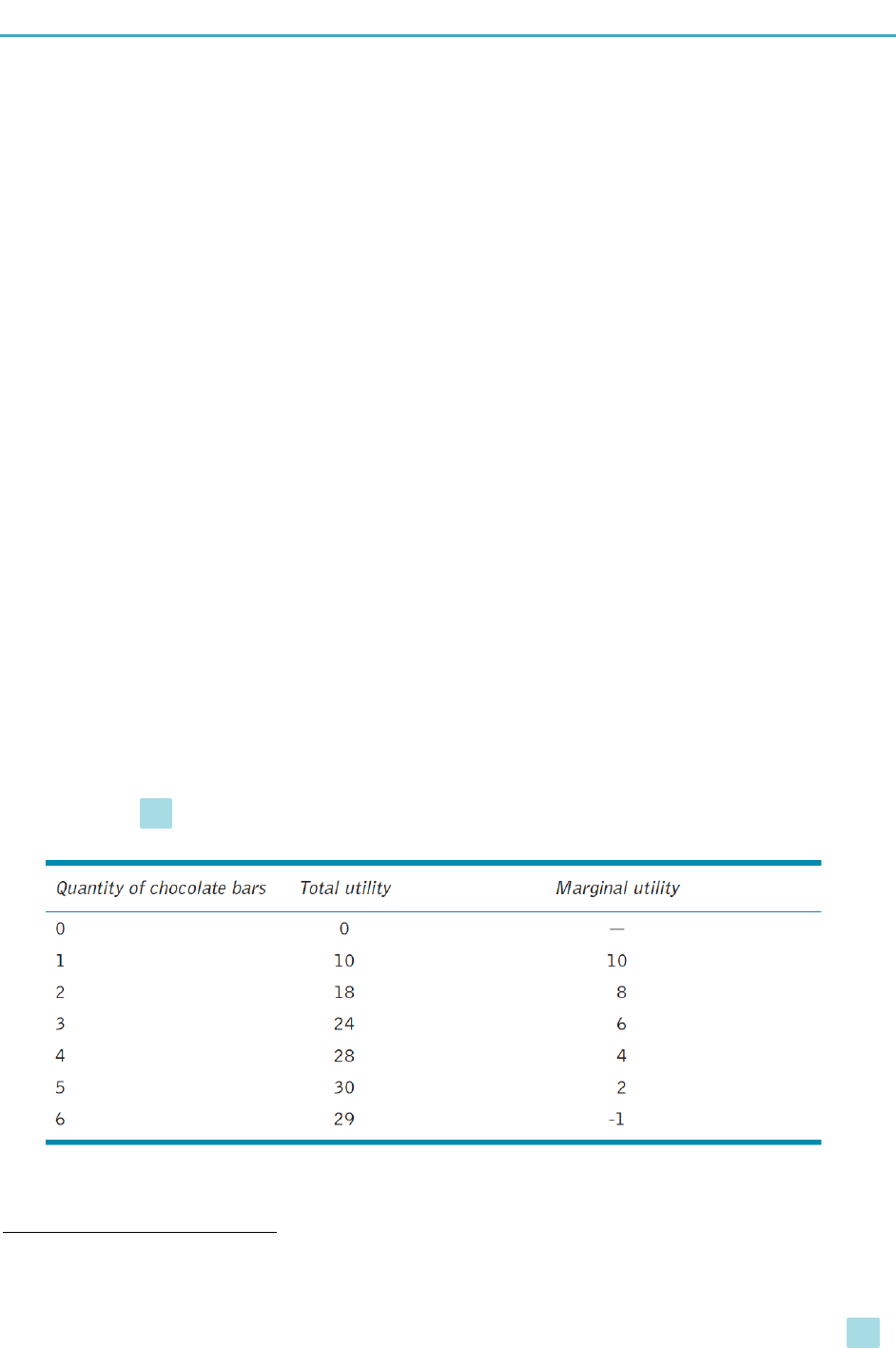

Thus Table 1 presents the total utility that Quong obtains from purchasing different quantities of

chocolate bars in a given period, say a day.

Table 1. Quong’s Utility from Consuming Chocolate Bars

5

Some economists in the 1800s, such as William Stanley Jevons (1835–1882) actually did believe that utility was

something that could eventually be measured numerically.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

10

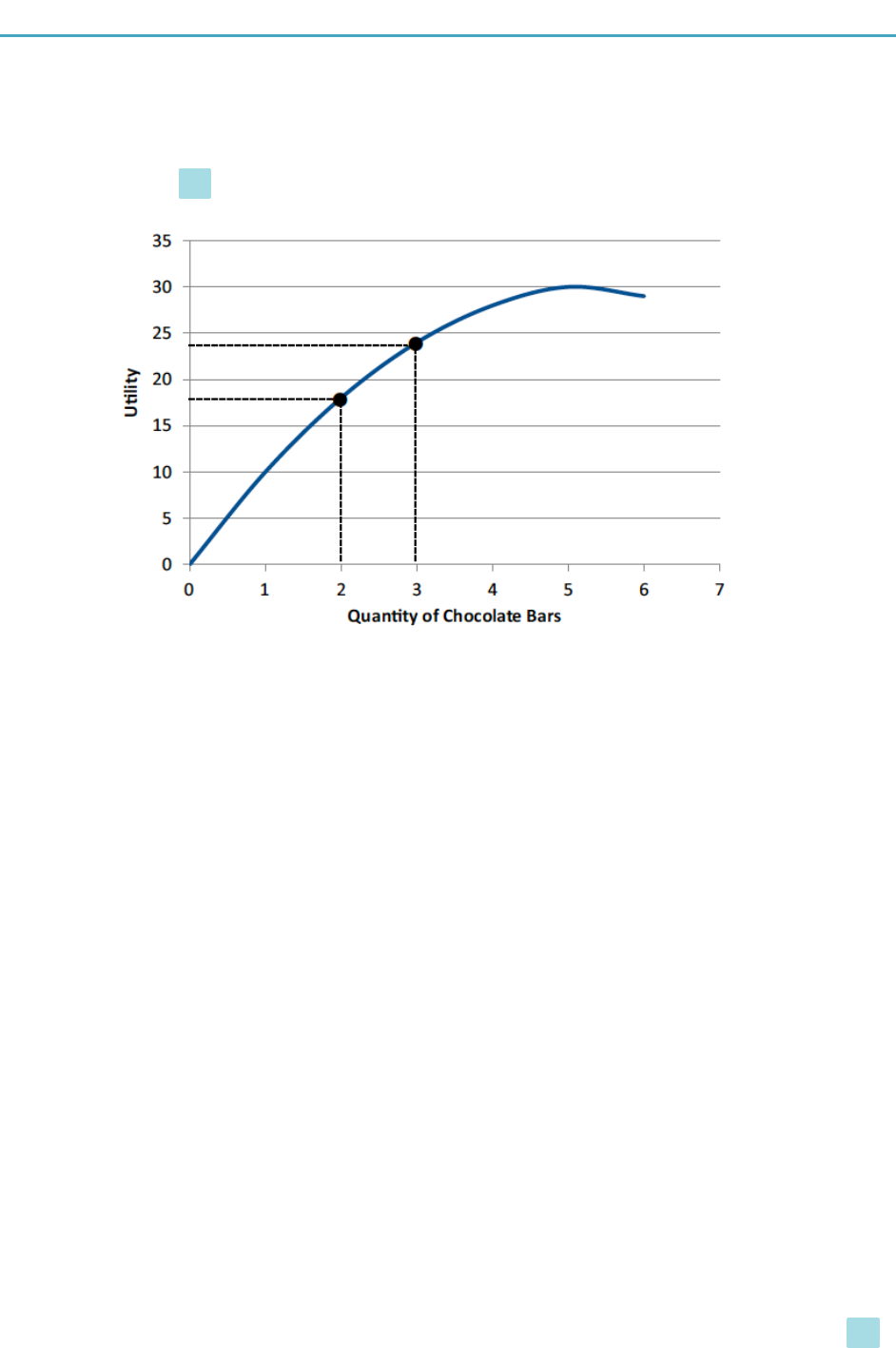

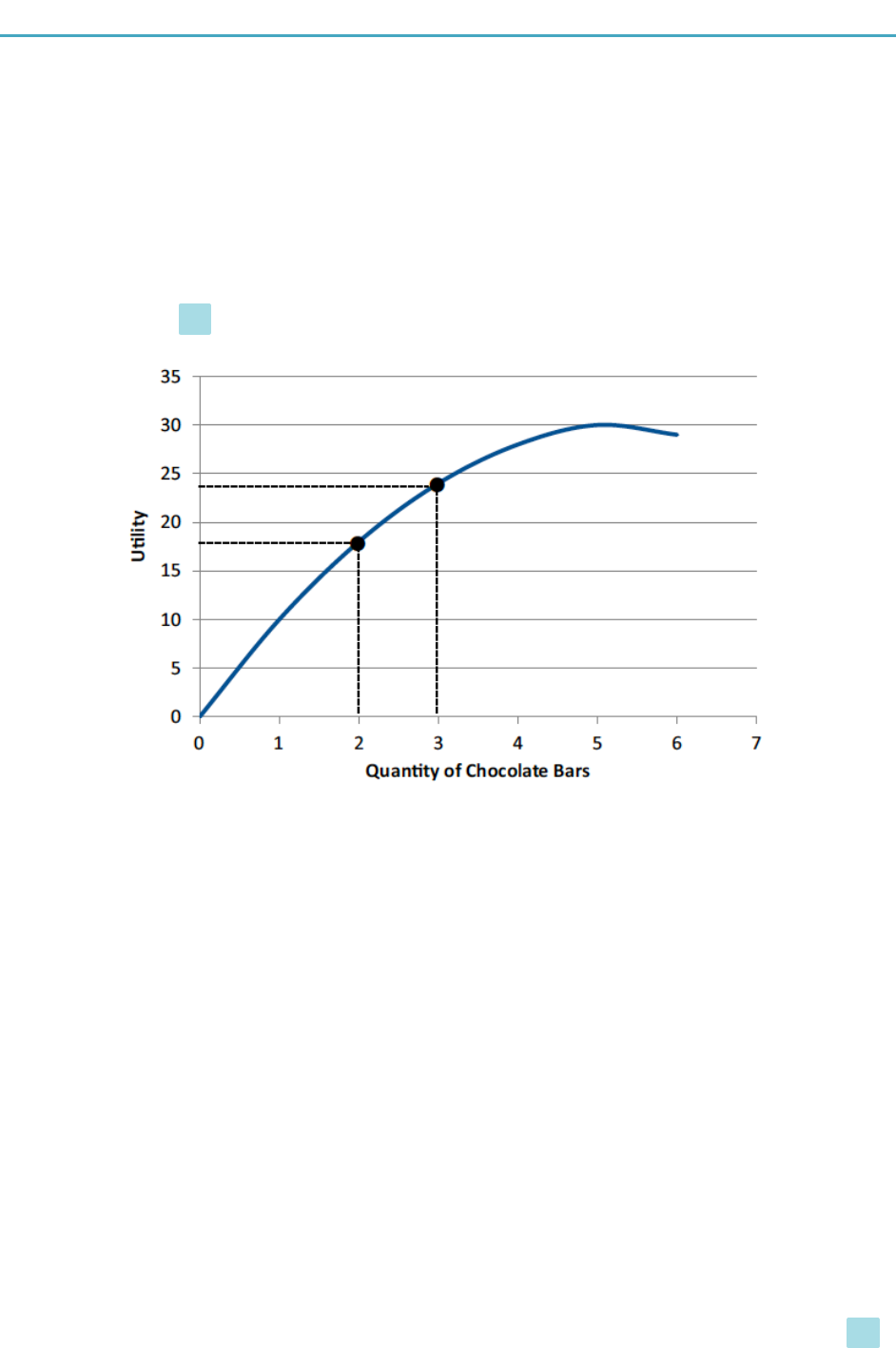

We can then plot Quong’s total utility from consuming chocolate bars in Figure 4. This relationship

between utility and the quantity of something consumed is called a utility function, or a total

utility curve.

Figure 4. Quong’s Utility Function for Chocolate Bars

Rather than looking at total utility, economists tend to focus on how utility changes from one level

of consumption to another. The change in utility for a one-unit change in consumption is known

as marginal utility. We can determine marginal utility by referring to Table 1. We see that Quong

obtains 10 units of “satisfaction” from consuming his first chocolate bar. While his utility increases

from 10 to 18 units by consuming his second chocolate bar, his marginal utility of the second

chocolate bar is only 8 units. Consuming his third chocolate bar, he obtains a marginal utility of 6

units.

We see in Figure 4 that Quong’s utility curve levels off as his consumption of chocolate bars

increases. This is generally expected—that successive units of something consumed provide less

utility than the previous unit. In other words, consumers’ utility functions generally display

diminishing marginal utility.

Now we can apply the concept of utility to the budget line that Quong faces. Realize that Quong

will also have a utility function for bags of nuts, which will display a similar pattern of diminishing

marginal utility. Let’s assume that his first bag of nuts provides him with 20 units of utility, his

second bag with 15 additional units, and his third bag with 10 additional units (more bags result in

even less units of utility). How can Quong allocate his limited budget to provide him with the

highest amount of total utility?

Using marginal thinking we can easily see how Quong can approach his problem in a purely

rational manner. Suppose that Quong is thinking about how he will spend his first $2. With $2 he

can buy either two chocolate bars or one bag of nuts. If he buys two chocolate bars, he will obtain

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

11

18 total units of utility, as shown in Table 1. If he buys one bag of nuts instead, he will obtain 20

units of utility. Thus, Quong will receive greater utility by spending his first $2 on a bag of nuts.

What about his next $2? If he spends this on his second bag of nuts, he obtains an additional 15

units of utility. But if he instead purchases his first two chocolate bars, he will obtain 18 units of

utility. So, by spending his next $2 on chocolate bars, he increases his utility by a greater amount.

After spending $4 Quong has purchased one bag of nuts and two chocolate bars, thus obtaining a

total utility of 38 units. Quong can continue to apply marginal thinking to maximize his utility

until he has eventually spent his entire budget. (Test yourself: How will Quong spend his third $2,

by buying another bag of nuts or two more bars of chocolate?)

6

The basic decision rule to maximize

utility is to allocate each additional dollar on the good or service that provides the greatest marginal

utility for that dollar.

7

2.4 Limitations of the Standard Consumer Model

We suspect that you have never thought about how to spend your money in a manner similar to

Quong’s marginal analysis of chocolate and nuts. It is less important that people behave exactly

as a model suggests than it is to consider whether people generally act as if they are always trying

to increase their utility as much as possible. There are several reasons to be skeptical about this.

First, the utility model assumes that people are rational. But this is not always the case. The model

also assumes that all the benefits from consumption can be identified, compared, and added up.

While comparing the utility from chocolate and nuts may be relatively easy to imagine, consumers’

decisions become much more complicated when they are faced with a wide variety of options.

Economists have traditionally assumed that having more options from which to choose can only

benefit consumers, but recent research demonstrates that there is a cost to trying to process

additional information. In fact, having too many choices can actually “overload” our ability to

evaluate different options. Consider a famous example demonstrating the effect of having too

much choice.

8

In one experiment, researchers at a supermarket in California set up a display table

with six different flavors of jam. Shoppers could taste any (or all) of the six flavors and receive a

discount coupon to purchase any flavor. About 30 percent of those who tried one or more jams

ended up buying some.

The researchers then repeated this experiment but, instead, offered 24 flavors of jam for tasting. In

this case, only 3 percent of those who tasted a jam went on to buy some. In theory, it would seem

that more choice would increase the chances of finding a jam that one really liked and would be

willing to buy. But, instead, the additional choices decreased one’s motivation to make a decision

to buy a jam. A 2010 article from The Economist addressed this topic:

6

If he buys his second bag of nuts, he will obtain 15 units of utility. If he buys two more chocolate bars, he will obtain

10 units of utility (6 units for his third bar, and 4 for his fourth bar). Thus he is better off buying another bag of nuts.

7

As most goods and services are not available in $1 increments, such as bags of nuts, consumers in this model will

not always be able to allocate every single dollar in a way that maximizes utility.

8

Iyengar and Lepper, 2000.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

12

As options multiply, there may be a point at which the effort required to obtain

enough information to be able to distinguish sensibly between alternatives

outweighs the benefit to the consumer of the extra choice. “At this point,” writes

Barry Schwartz in The Paradox of Choice, “choice no longer liberates, but

debilitates. It might even be said to tyrannise.” In other words, as Mr. Schwartz puts

it, “the fact that some choice is good doesn’t necessarily mean that more choice is

better.”

Daniel McFadden, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley, says that

consumers find too many options troubling because of the “risk of misperception

and miscalculation, of misunderstanding the available alternatives, of misreading

one’s own tastes, of yielding to a moment’s whim and regretting it afterwards,”

combined with “the stress of information acquisition.”

9

Another important point is that when consumers make a decision to purchase a good or service,

they are essentially making a prediction about the utility that the purchase will bring them. Daniel

Kahneman distinguishes between predicted utility and remembered utility. Predicted utility is the

utility that you expect to obtain from a purchase (or other experience), whereas remembered utility

is the utility that you actually recall after you have made a purchase. In other words, Kahneman

considers whether people actually receive the benefits they expect in advance of their purchases.

According to the standard consumer model with rational decision makers, these two utilities should

match relatively closely.

Once again research from behavioral economics suggests that people’s predictions can often turn

out to be incorrect. In one well-known experiment, young professors were asked to predict the

effect of their tenure decision on their long-term happiness. Although being granted tenure

essentially ensures a professor lifetime employment, being denied tenure means he or she must

find a new job. Most young professors predict that being denied tenure will have a long-term

negative impact on their happiness. Yet surveys of professors who actually have and have not been

granted tenure indicate that there is no significant long-term effect of tenure decision on happiness

levels. A similar experiment showed that college students over-predicted the negative effects of a

romantic breakup.

10

These findings have implications for welfare analysis. Realize that a demand curve is an expression

of predicted utility. Welfare analysis measures consumer surplus based on demand curves, thus

implicitly assuming that predicted utility matches well with remembered utility. But if predicted

and remembered utility differs, any welfare implications based on demand curves will be

inaccurate— not reflective of the utility that people actually receive from their purchases.

We must also recognize the potential for consumers to be swayed by advertising and other

influences into making poor consumer decisions. Advertising expenditures in the United States

totaled about $200 billion in 2016, equivalent to more than $600 per person.

11

Of course, the

9

Anonymous, 2010.

10

Gilbert et al., 1998.

11

Advertising Age, 2015.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

13

purpose of advertising is not necessarily to assist consumers to make the best choices. We further

discuss the impact of advertising later in this module.

3. CONSUMPTION IN HISTORICAL AND INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT

Perhaps the greatest limitation of the neoclassical consumer model is that it does not really tell us

anything interesting about why consumers make particular choices. For example, why might

Quong purchase so many chocolate bars that it has a negative impact on his health? Can someone

who smokes cigarettes truly be acting in a utility-maximizing manner? Why do people acquire

huge credit card debts by making seemingly frivolous purchases? Why would someone spend

$60,000 or more on a new car when a car costing much less may be perfectly adequate for all

practical purposes?

To answer such questions, we must recognize the historical and social nature of consumption. We

are so immersed in a culture of consumption that we can be said to be living in a consumer society,

a society in which a large part of people’s sense of identity and meaning is achieved through the

purchase and use of consumer goods and services. Viewing consumption through the lens of a

consumer society is quite different from looking at consumption from the neoclassical model of

consumer behavior.

We first consider the historical evolution of consumer society, along with the institutions that

allowed consumer society to flourish. Then we take a brief look at consumer society around the

world today.

3.1 A Brief History of Consumer Society

When can we say that consumer society originated? Historians have placed the birth of the

consumer society variously from the sixteenth century to the mid-1900s.

12

To some extent, the

answer depends on whether we consider consumerism, understood as having one’s sense of

identity and meaning defined largely through the purchase and use of consumer goods and

services, as an innate human characteristic. In other words, does consumerism come naturally to

humans or is it an acquired trait? Of course, for thousands of years in many societies a small elite

class has existed that enjoyed higher consumption standards and bought luxury goods and services.

One story of the birth of consumer society says that it is human nature to want to acquire more

goods, so all that is needed for the birth of consumer society is for a significant portion of the

population to have more money than is necessary for basic survival. However, this explanation is

incorrect or at least a vast oversimplification.

Before the eighteenth century, families and communities that acquired more than enough to meet

basic needs did not automatically respond by becoming consumers. Religious value systems

generally taught material restraint. Patterns of dress and household display were dictated by

tradition, depending on the class to which one belonged, with little change over time. Unlike the

12

Material from this section is drawn primarily from Stearns, 2006.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

14

norm in modern times, in the past emphasis was more often placed on community spending, such

as for a new church, as opposed to private spending.

The historical consensus is that consumer society as a mass phenomenon originated in the

eighteenth century in Western Europe. Although it is no coincidence that this time and location

coincides with the birth of the Industrial Revolution, consumer society was not solely the result of

greater prosperity. The Industrial Revolution clearly transformed production. It is less obvious, but

equally true, that it transformed consumption, as much through the social changes it produced as

through the economic changes.

The arrival of consumerism in Western Europe involved truly revolutionary change

in the way goods were sold, in the array of goods available and cherished, and in

the goals people defined for their daily lives. This last—the redefinition of needs

and aspirations—is the core feature of consumerism.

13

The large-scale emigration of people from the agricultural countryside to cities in search of work

brought significant social disruption. Instead of finding personal and social meaning in tradition

and community, as they had in the past, people sought new ways to define themselves, often

through consumer goods. Shopkeepers for the first time began to create window displays, engage

in newspaper advertising, and use other methods to attract customers. Furthermore, the breakdown

of strict class lines meant that common people had the freedom to express themselves in new ways,

including displays of wealth that would have been discouraged, or even illegal, in the past.

Although consumerism took root in the eighteenth century, it took some time before it fully

blossomed. At the dawn of industrialization, it was not at all clear that workers would become

consumers. Early British industrialists complained that their employees would work only until they

had earned their traditional weekly income and then stop until the next week. Leisure, it appeared,

was more valuable to the workers than increased income. This attitude, widespread in pre-

industrial societies, was incompatible with mass production and mass consumption. It could be

changed in either of two ways.

At first, employers responded by lowering wages and imposing strict discipline on workers to force

them to work longer hours. Early textile mills frequently employed women, teenagers, and even

children, because they were easier to control and could be paid less than adult male workers. As a

consequence of such draconian strategies of labor discipline, living and working conditions for the

first few generations of factory workers were generally worse than in the generations before

industrialization.

Over time, however, organized workers, political reformers, and humanitarian groups pressured

for better wages, hours, and working conditions, while rising productivity made businesses more

open to meeting some of these demands. A second response to the pre-industrial work ethic

gradually evolved: As workers came to see themselves as consumers, they would no longer choose

to stop work early and enjoy more leisure. Instead, they preferred to work full-time, or even

overtime, in order to earn and spend more. In the United States, the “worker as consumer” view

13

Stearns, 2006, p. 25.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

15

was fully entrenched by the 1920s, when the labor movement stopped advocating a shorter

workweek and instead focused on better wages and working conditions.

Other historical developments were important to the spread of consumer society. One was the

invention of the department store, in the mid-nineteenth century in England. Department stores

quickly spread to other European countries and the United States. Featuring lavish displays,

department stores presented shoppers with the opportunity to purchase an entirely new lifestyle,

all under one roof. Department stores introduced the idea of shopping as “spectacle,” with

entertainment, elaborate interiors, seasonal displays, and parades.

14

The department store was a permanent fair, a dream world, a spectacle of excessive

proportions. Going to the store became an event and an adventure. One came less

to purchase a particular article than to simply visit, to browse, to see what was new,

to try on new fashions and even new identities.

15

Modern shopping malls originated in the United States in the early twentieth century.

Suburbanization in the United States in the mid-twentieth century was supported by the

construction of large shopping malls far from city centers but easily accessible by automobile. By

the 1980s and 1990s enormous shopping malls, such as the Mall of America in Minnesota, were

being constructed with entertainment options including indoor roller coasters and aquariums.

Another institution created to support consumerism was expanded consumer credit, particularly

the invention of credit cards in the 1940s. Although some cardholders use them only for

convenience, paying off their balances in full each month, about half of cardholders use them as a

form of borrowing by carrying unpaid balances, on which they pay interest, with annualized rates

that can exceed 30 percent.

16

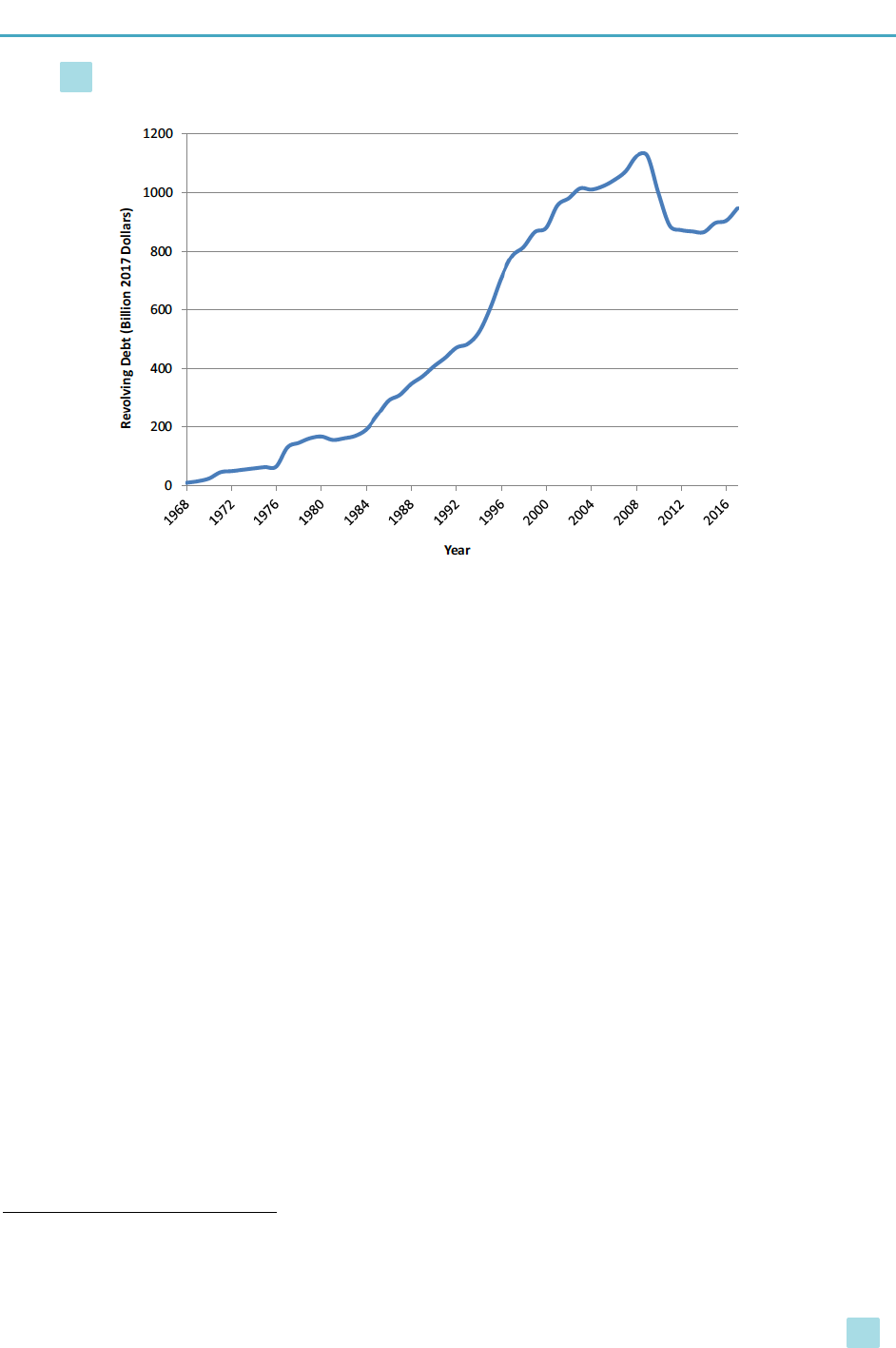

Figure 5 illustrates the growth of revolving debt in the United States over the past several decades,

adjusted for inflation.

17

We see that revolving debt, which consists almost entirely of credit card

debt, increased by a factor of 100 from 1968 until about 2007, when the Great Recession caused

households to reduce their debt, as spending declined and credit became less available. More

recently credit card debt has begun to rise again, although it hasn’t yet reached the peak level prior

to the financial crisis. In mid-2017, total outstanding revolving debt in the United States was about

$960 billion, equivalent to more than $7,600 per household. However, given that about half of

households do not carry an unpaid monthly balance on their credit cards, those households that do

carry a balance had an average credit card debt of around $15,000.

14

Ritzer, 1999.

15

Goodman and Cohen, 2004, p. 17.

16

Wolff-Mann, 2016.

17

Revolving debt allows consumers to borrow money against a line of credit, without the requirement that the amount

borrowed be fully paid off each month. Thus the balance from one or more months can carry over, or “revolve,” to

the next month. The vast majority of revolving debt is credit card debt.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

16

Figure 5. Revolving Debt in the United States, 1968-2017, Adjusted for Inflation

Sources: Federal Reserve, Consumer Credit (G.19); CPI data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

3.2 Limits to Modern Consumerism

Can we say, at the start of the twenty-first century, that consumerism has become a global

phenomenon? It is true that people all over the world are increasingly exposed to similar

commercial messages and images of “the good life,” but consumer society is not yet universal for

two main reasons. First, the majority of people around the world are simply too poor to be

considered modern consumers. Over 700 million people, about 10 percent of humanity, live in

“extreme” poverty, defined by the World Bank as living on less than $1.90 per day.

18

Even further,

71 percent of the world’s population lives on less than $10 per day, according to a 2015 report.

19

While an income of $10 per day is considered the minimum necessary for a degree of economic

security, it is not enough to support a consumerist lifestyle. The second reason consumerism is not

yet universal is that in numerous places around the world cultural and religious values exist that

seek to restrain, or even reject, the consumer society. We first discuss global poverty and then turn

to a brief discussion of nonconsumer values.

Insufficient Consumption: Poverty

Poverty is about more than just a low income. The United Nations defines absolute deprivation

as “a condition characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe

drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education and information. It depends not only

on income but also on access to services.”

20

The poorest of developing countries, particularly in

18

http://povertydata.worldbank.org/poverty/home/.

19

Kochhar, 2015.

20

http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/wssd/text-version/agreements/poach2.htm.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

17

sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia, often lack the resources needed to lift their populations out

of absolute deprivation. Increasingly, however, the more economically successful developing

countries in Asia and Latin America have sufficient resources to provide everyone with basic

necessities. The fact that absolute deprivation still exists for the poor in these countries reflects

inequality in the distribution of income. Absolute deprivation may also vary with factors such as

race and ethnicity and even within a household on the basis of age or gender.

Because insufficient consumption is not simply a matter of having a low household income,

however, even in regions that could be generally characterized as middle or high income, examples

of absolute deprivation can still be found. Some people—particularly young children and the ill

and handicapped—have dependency needs for care that may be unmet. Even people with a fairly

high household income by global standards may sometimes find themselves lacking basic

necessities. Advocates for the elderly, the sick, and children, for example, often claim that the

United States has an inadequate system of care.

Absolute deprivation is only one type of insufficiency. Modern technology means that nearly

everyone has some exposure to the “lifestyles of the rich and famous.” The result is the creation

of widespread feelings of relative deprivation, that is, the sense that one’s own condition is

inadequate because it is inferior to someone else’s circumstances. Relative deprivation is a

condition that exists in all countries to some extent. The government-defined poverty level in the

United States was $24,600 for a family of four in 2017.

21

This income would be at or above the

national average in many countries; in most developing countries, a family income of $24,600

would be considered wealthy. It may be possible to buy the bare physical necessities of life for

this sum, even in the United States—at least in areas of the country with low housing costs. Yet it

is likely that most of the Americans who fall below the poverty level (13 percent of the population

in 2016

22

) do not feel able to enjoy a “normal” American lifestyle. They clearly do not have the

resources to buy the kinds of homes, cars, clothing, and other consumer goods commonly shown

on American television. The 18 percent of U.S. children who live in poverty

23

do not start out on

an “even playing field” with nonpoor children, in terms of nutrition, health care, and other

requirements. The fact that people who cannot afford to consume at “normal” societal consumption

levels feel relative deprivation suggests that poverty, even relative poverty, is not conducive to

promoting well-being and self-respect.

Nonconsumerist Values

The spread of consumerism has met considerable resistance in some societies, usually because it

conflicts with existing values, either religious or secular. For example, the Muslim concept of riba

prohibits charging interest on loans. Buddhism teaches a “middle path” that emphasizes material

simplicity, nonviolence, and inner peace. Various passages of the New Testament of the Bible

emphasize the spiritual dangers of wealth, such as the saying that it is easier for a camel to pass

through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter heaven.

Traditional cultural values in some countries have restrained the spread of consumerism. In some

countries, consumerism is associated with foreign, typically American, values.

21

https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines.

22

Semega et al., 2017.

23

Ibid.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

18

Consumption expansion thus tends to lead to some level of global homogenization

of culture among consumers, an effect that gives rise to negative responses to

globalization. As consumer goods are always also cultural goods, expansion of

consumption of imported products and services often gives rise to an exaggerated

sense of “panic,” of cultural “invasion” which, supposedly, if left unchecked will

result in the demise of the local culture.

24

Social norms and government policies in various European countries aim to promote

nonconsumerist values. For example, many retail stores in France, Italy, and other European

countries are normally closed at lunchtime and on Sundays. European policies on vacation time,

parental leave, and flexible working hours emphasize a work–life balance.

Even in the United States, the spread of consumerism has not been an even, uninterrupted process.

The history of consumer society in the United States reveals periodic movements against

consumerism. The Quakers in the eighteenth century, the Transcendentalists of the mid-nineteenth

century (most famously, Henry David Thoreau), the Progressives at the turn of the twentieth

century, and the hippies of the 1960s all espoused a simpler, less materialistic life philosophy.

25

More recently, starting in the 1980s the idea of voluntary simplicity, which we discuss further later

in the module, has attracted a following among Americans motivated by objectives such as

reducing environmental impacts, focusing more on family and social connections, healthy living,

and stress reduction.

4. CONSUMPTION IN A SOCIAL CONTEXT

As mentioned at the beginning of this module, in modern consumer societies consumption is as

much a social activity as an economic activity. Consumption is tied closely to personal identity,

and it has become a means of communicating social messages. An increasing range of social

interactions are influenced by consumer values.

Consumption pervades our everyday lives and structures our everyday practices.

The values, meanings, and costs of what we consume have become an increasingly

important part of our social and personal experiences… [Consumption] has entered

into the . . . fabric of modern life. All forms of social life—from education to sexual

relations to political campaigns—are now seen as consumer relations.

26

4.1 Social Comparisons

As social beings, we compare ourselves to other people. Our income and consumption levels are

some of the most important ways in which we evaluate ourselves relative to others. As discussed

above, whether people consider themselves poor often depends on the condition of those around

them.

24

Goodman and Cohen, 2004, p. 68.

25

See Shi, 2007.

26

Goodman and Cohen, 2004, pp. 1–4.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

19

You have probably heard of the saying “Keeping up with the Joneses.” This saying refers to the

motivation to maintain a material lifestyle that is comparable to those around us. A reference

group is a group of people who influence the behavior of consumers because they compare

themselves with that group. Most people have various reference groups, traditionally including our

neighbors, our coworkers, and other members of our family. We also are influenced as consumers

by aspirational groups, groups to which a consumer wishes he or she could belong. People often

buy, dress, and behave like the group—corporate executives, rock stars, athletes, or whoever—

with whom they would like to identify.

Economist Juliet Schor argues that the nature of social comparisons related to consumption has

changed in the past few decades. She suggests that in the 1950s and 1960s the idea of “Keeping

up with the Jones” emphasized comparisons between individuals or families with similar incomes

and backgrounds. Because prosperity was broadly shared in the postwar decades, people did not

want to feel left out as new consumer goods and living standards emerged. More recently, however,

she has observed a different approach to consumption comparisons.

Beginning in the 1980s, those conditions changed, and what I have termed the new

consumerism emerged. The new consumerism is more upscale in the sense that

there is more aggressive, rather than defensive, consumption positioning. The new

consumerism is more anonymous and is less socially benign than the old regime of

keeping up with the Joneses. In part, this is because reference groups have become

vertically elongated. People are now more likely to compare themselves with, or

aspire to the lifestyle of, those far above them in the economic hierarchy.

27

Schor presents the results of a survey to support this view, which indicates that 85 percent of

respondents aspire to become someone who “really made it” or is at least “doing very well.” But

the survey results also show that only 18 percent of Americans are members of these groups based

on income.

28

If 85 percent of people aspire to be in the top 18 percent, obviously most will end up

disappointed.

Changes in economic inequality are also relevant to her hypothesis. During the 1950s and 1960s,

economic inequality in the United States was decreasing—that is, the gap between different levels

of the income hierarchy was generally shrinking. However, beginning in the 1970s economic

inequality began to increase, thus making it difficult to even maintain the existing distance between

an individual and his or her aspirational group.

Media representations of wealthy lifestyles also became more common. In the 1950s and 1960s,

most television shows depicted middle-class lifestyles. But starting in the 1980s, television shows

as well as advertisements increasingly depicted upper-class lifestyles. Exposure to media

representations of wealth influences people’s values and spending patterns. Schor’s own research

indicates that the more television a person watches, the more he or she is likely to spend, holding

constant other variables such as income. Higher rates of television watching have also been

associated with having materialistic values.

29

Other research has found that heavy television

27

Schor, 1999, p. 43.

28

Schor, 1998.

29

Shrum et al., 2005.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

20

watchers are likely to overstate the percentage of the population that owns luxury items, such as

convertibles and hot tubs, or that have maids or servants.

30

Schor’s conclusion is that identifying with unrealistic aspirational groups leads many people to

consume well above their means, acquiring large debts and suffering frustration as they attempt to

join those groups through their consumption patterns but fail to achieve the income to sustain them.

As people tend to evaluate themselves relative to reference and aspirational groups, with increasing

inequality some may feel as if they are falling behind even if their incomes are actually increasing.

The more our consumer satisfaction is tied to social comparisons—whether

upscaling, just keeping up, or not falling too far behind—the less we achieve when

consumption grows, because the people we compare ourselves to are also

experiencing rising consumption. The problem is not just that more consumption

doesn’t yield more satisfaction, but that it always has a cost. The extra hours we

have to work to earn the money cut into personal and family time. Whatever we

consume has an ecological impact. We find ourselves skimping on invisibles such

as insurance, college funds, and retirement savings as the visible commodities

somehow become indispensable. We are impoverishing ourselves in pursuit of a

consumption goal that is inherently unattainable. In the words of one focus-group

participant, we “just don’t know when to stop and draw the line.”

31

4.2 Advertising

Although advertising has existed as a specialized profession for only about a century, it has become

a force that rivals education and religion in shaping public values and aspirations. We already saw

that advertising spending in the United States totals about $600 per person annually. According to

one estimate, Americans are exposed to around 5,000 commercial messages per day, up from

around 2,000 per day in the 1980s.

32

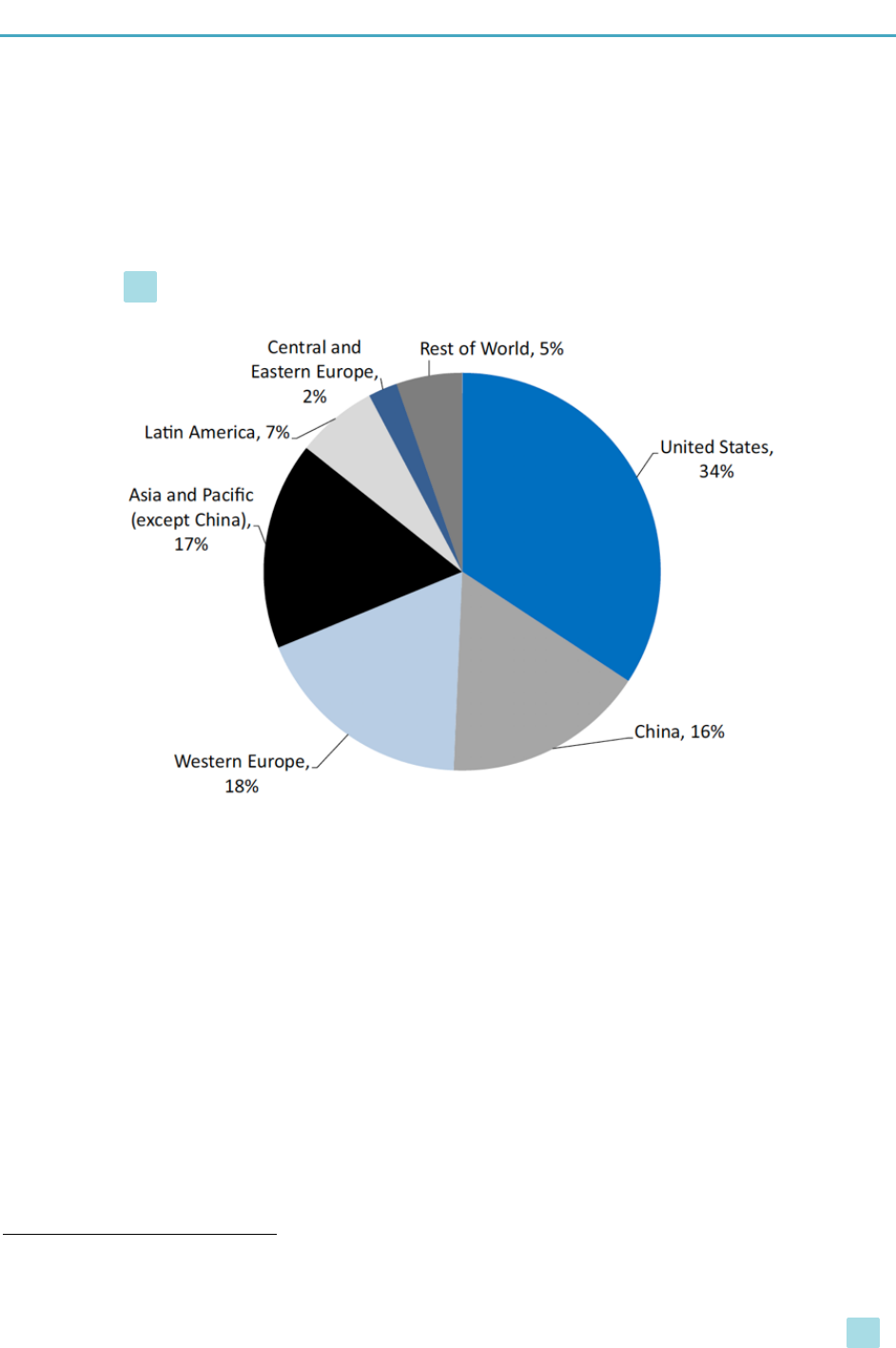

Global advertising expenditures were about $520 billion in 2016, equivalent to the national

economy of Argentina or Sweden. About one-third of global advertising spending takes place in

the United States (see Figure 6). China recently became the world’s second-largest advertising

market. Per-capita advertising spending in China increased from just 9 cents in 1986 to $61 in

2016.

Advertising is often justified by economists as a source of information about products and services

available in the marketplace. Although it certainly plays that role, it also does much more.

Advertising appeals to many different values, emotional as well as practical needs and a range of

desires and fantasies. The multitude of advertisements that we encounter carry their own separate

messages; yet on a deeper level, they all share a common, powerful cultural message.

30

O’Guinn and Shrum, 1997.

31

Schor, 1998, pp. 107–109.

32

Story, 2007.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

21

What the vast amount of advertising really sells is consumer culture itself. Even if

advertising fails to sell a particular product, the advertisements still sell the

meanings and values of a consumer culture. As Christopher Lasch writes, “The

importance of advertising is not that it invariably succeeds in its immediate purpose,

…but simply that it surrounds people with images of the good life in which

happiness depends on consumption. The ubiquity of such images leaves little space

for competing conceptions of the good life.”

33

Figure 6. Advertising Expenditures, by Country/Region, 2016

Source: Advertising Age, 2015.

According to one estimate, the typical American will spend about three years of his or her life

watching television ads.

34

We have already mentioned how watching television can influence

people’s spending behavior and values. Other research details how television, and advertising in

particular, is associated with obesity, attention deficit disorder, heart disease, and other negative

consequences. Furthermore, advertising commonly portrays unrealistic body images, traditionally

for women but more recently for men as well. (See Box 1 for more on the effects of advertising on

girls and women.)

33

Goodman and Cohen, 2004, pp. 39–40.

34

Holt et al., 2007.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

22

BOX 1: WOMEN AND ADVERTISING

A 2007 report by the American Psychological Association concluded that advertising and other

media images encourage girls to focus on physical appearance and sexuality, with harmful results

for their emotional and physical well-being.

35

The research project reviewed data from numerous

media sources, including television, music videos and lyrics, movies, magazines, and video games.

The report found that 85 percent of the sexualized images of children were of girls.

The lead author of the report, Dr. Eileen L. Zurbriggen, said, “The consequences of the

sexualization of girls in media today are very real and are likely to be a negative influence on girls’

healthy development. We have ample evidence to conclude that sexualization has negative effects

in a variety of domains, including cognitive functioning, physical and mental health, and healthy

sexual development.”

Three of the most common mental health problems associated with exposure to sexualized images

and unrealistic body ideals are eating disorders, low self-esteem, and depression. It is estimated

that 8 million Americans suffer from an eating disorder—7 million of them women. About 20

percent of anorexics will eventually die from the disorder.

36

According to a 2012 article, most

female models would be considered anorexic according to their body mass index. Twenty years

ago the average model weighed 8 percent less than the average woman; now it is 23 percent less.

37

Jean Kilbourne, an author and filmmaker who holds a Ph.D. in education, has been lobbying for

advertising reforms since the 1960s. She has produced four documentaries on the negative effects

of advertising on women, most recently in 2010, under the title Killing Us Softly. Kilbourne notes

that virtually all photos of models in advertisements have been touched up, eliminating wrinkles,

blemishes, extra weight, and even skin pores. She believes that we need to change the environment

of advertising through public policy.

38

Dr. Zurbriggen concludes, “As a society, we need to replace

all of these sexualized images with ones showing girls in positive settings—ones that show the

uniqueness and competence of girls.”

4.3 Private Versus Public Consumption

The growth of consumerism has altered the balance between private and public consumption.

Public infrastructure has been shaped by the drive to sell and consume new products and the

availability of public and private options, in turn, shapes individual consumer choices.

In the early 1930s, for example, many major U.S. cities—including Los Angeles— had extensive,

relatively efficient, and nonpolluting electric streetcar systems. Then, in 1936, a group of

35

Anonymous, 2007.

36

South Carolina Department of Mental Health, Eating Disorder Statistics, www.state.sc.us/dmh/anorexia

37

Lovett, 2012.

38

Jean Kilbourne Web site, www.jeankilbourne.com.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

23

companies involved in bus and diesel gasoline production, led by General Motors, formed a group

called the National City Lines (NCL). They bought up electric streetcar systems in 45 cities and

dismantled them, replacing them with bus systems that also tended to promote automobile

dependency.

39

U.S. government support for highway construction in the 1950s further hastened

the decline of rail transportation, made possible the spread of suburbs far removed from

workplaces, and encouraged the purchase of automobiles.

Many of the choices that you have, as an individual, depend on decisions made for you by

businesses and governments. Los Angeles would look much different today—more like the older

sections of many East Coast and European cities—if it had been built up around streetcar lines

rather than cars and buses. Even today one can see tradeoffs between public (or publicly accessible)

infrastructure and private consumption. As more people carry cell phones and bottled water, pay

telephones and drinking fountains either cease to exist or become less well maintained, leading

more people to carry cell phones and bottled water.

5. CONSUMPTION IN AN ENVIRONMENTAL CONTEXT

The production process that creates every consumer product requires natural resources and

generates some waste and pollution. However, we are normally only vaguely aware of the

ecological impact of the processes that supply us with consumer goods.

The problem is that we do not often see the true ugliness of the consumer economy

and so are not compelled to do much about it. The distance between shopping malls

and their associated mines, wells, corporate farms, factories, toxic dumps, and

landfills, sometimes half a world away, dampens our perceptions that something is

fundamentally wrong.

40

Most of us are unaware that, for example, it requires about 600 gallons of water to make a quarter-

pound hamburger or that making a computer chip generates 4,500 times its weight in waste.

41

(For

another example of the ecological impacts of consumption, see Box 2.)

BOX 2: THE ENVIRONMENTAL STORY OF A T-SHIRT

T-shirts, along with jeans, are perhaps the most ubiquitous articles of clothing on college

campuses. What is the environmental impact of each of these T-shirts?

42

Consider a T-shirt constructed of a cotton/polyester blend, weighing about four ounces. Polyester

39

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_City_Lines.

40

Orr, 1999, pp. 145–146.

41

Ryan and Durning, 1997.

42

Material drawn from Ryan and Durning, 1997.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

24

is made from petroleum—a few tablespoons are required to make a T-shirt. During the extraction

and refining of the petroleum, one-fourth of the polyester’s weight is released in air pollution,

including nitrogen oxides, particulates, carbon monoxide, and heavy metals. About 10 times the

polyester’s weight is released in carbon dioxide, contributing to global climate change.

Cotton grown with nonorganic methods relies heavily on chemical inputs. Cotton accounts for 10

percent of the world’s use of pesticides. A typical cotton crop requires six applications of

pesticides, commonly organophosphates that can damage the central nervous system. Cotton is

also one of the most intensely irrigated crops in the world. T-shirt fabric is bleached and dyed with

chemicals including chlorine, chromium, and formaldehyde. Cotton resists coloring, so about one-

third of the dye may be carried off in the waste stream. Most T-shirts are manufactured in Asia

and then shipped by boat to their destination, with further transportation by train and truck. Each

transportation step involves the release of additional air pollution and carbon dioxide.

Despite the impacts of T-shirt production and distribution, most of the environmental impact

associated with T-shirts occurs after purchase. Washing and drying a T-shirt just 10 times requires

about as much energy as was needed to manufacture the shirt. Laundering will also generate more

solid waste than the production of the shirt, mainly from sewage sludge and detergent packaging.

How can one reduce the environmental impacts of T-shirts? One obvious step is to avoid buying

too many shirts in the first place. Buy shirts made of organic cotton or recycled polyester or

consider buying used clothing. Wash clothes only when they need washing, not necessarily every

time you wear something. Make sure that you wash only full loads of laundry and wash using cold

water whenever possible. Finally, avoid using a clothes dryer—clothes dry naturally for free by

hanging on a clothesline or a drying rack.

5.1 The Link Between Consumption and the Environment

In quantifying the ecological impacts of consumerism, most people focus on the amount of “trash”

generated by households and businesses. In 2014, the U.S. economy generated over 250 million

tons of municipal solid waste, which consisted mostly of paper, food waste, and yard waste.

Although the total amount of municipal solid waste generated has increased in recent decades (an

increase of nearly 200 percent since 1960), the portion recycled has increased from around 6

percent in the 1960s to about 35 percent today.

43

But most of the waste generation in a consumer society occurs during the extraction, processing,

or manufacturing stages—these impacts are normally hidden from consumers. According to a 2012

analysis, the U.S. economy requires about 8 billion tons of material inputs annually, which is

equivalent to more than 25 tons per person.

44

The vast majority of this material is discarded as

mining waste, crop residue, logging waste, chemical runoff, and other waste prior to the

consumption stage.

43

U.S. EPA, 2016.

44

Gierlinger and Krausmann, 2012.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

25

Perhaps the most comprehensive attempt to quantify the overall ecological impact of consumption

is the ecological footprint measure. This approach estimates how much land area a human society

requires to provide all that it takes from nature and to absorb its waste and pollution. Although the

details of the ecological footprint calculations are subject to debate, it does provide a useful way

to compare the overall ecological impact of consumption in different countries.

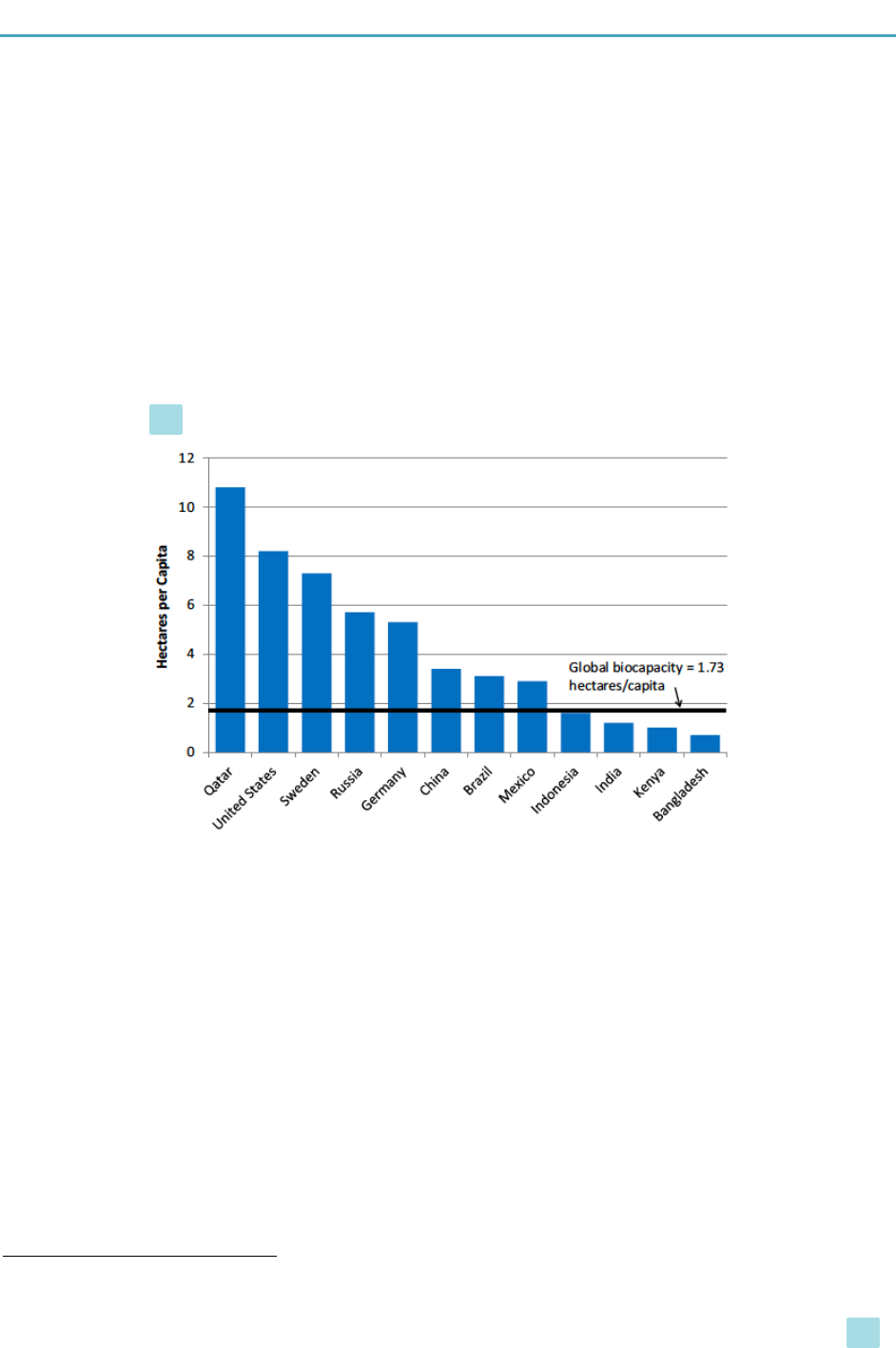

We see in Figure 7 that the ecological footprint per capita varies significantly across countries.

The United States has one of the highest per-capita ecological footprints (the per-capita footprints

of only four countries are higher, including Qatar and Australia).

45

The average European has a

footprint about 40 percent lower than the U.S. level, while the typical Chinese has a footprint 60

percent lower. The average Indian has an ecological footprint seven times lower than the average

American.

Figure 7. Ecological Footprint per Capita, Select Countries, 2012

Source: Global Footprint Network, 2016.

Perhaps the most significant implication of the ecological footprint research is that the world is

now in a situation of “overshoot”—our global use of resources and generation of waste exceeds

the global capacity to supply resources and assimilate waste, by about 60 percent. As seen in Figure

7, the total amount of productive area available on earth (the “biocapacity”) is only 1.73 hectares

per person. In other words, for humans to live in an ecologically sustainable manner, the average

person’s ecological impacts could only be about that of the average Indonesian. Obviously, the

situation is much worse when we consider that an increasing number of people in the world seek

to consume at a level equivalent to the typical American. If everyone had the same ecological

impacts as the typical American, we would require 4.7 earths to provide the needed resources and

assimilate the waste.

45

Global Footprint Network, 2016.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

26

5.2 Green Consumerism

Green consumerism means making consumption decisions at least partly on the basis of

environmental criteria. Clearly, green consumerism is increasing: More people are recycling, using

reusable shopping bags and water containers, buying hybrid or electric cars, and so on. Yet some

people see green consumerism as an oxymoron—that the culture of consumerism is simply

incompatible with environmental sustainability.

Whether green consumerism is an oxymoron depends on exactly how we define it. Green

consumerism comes in two basic types:

1. “shallow” green consumerism: consumers seek to purchase “ecofriendly” alternatives but

do not necessarily change their overall level of consumption

2. “deep” green consumerism: consumers seek to purchase ecofriendly alternatives but also,

more importantly, seek to reduce their overall level of consumption

Someone who adheres to shallow green consumerism might buy a hybrid or electric car instead of

a car with a normal gasoline engine or a shirt made with organic cotton instead of cotton grown

with the use of chemical pesticides. But those who practice deep green consumerism would, when

feasible, take public transportation instead of buying a car and question whether they really need

another shirt. In other words, in shallow green consumerism the emphasis is on substitution while

in deep green consumerism the emphasis is on a reduction in consumption. Note that people who

buy so-called ecofriendly products such that their overall consumption increases, or as status

symbols, could hardly be said to be practicing green consumerism.

Ecolabeling helps consumers make environmentally conscious decisions. An ecolabel can provide

summary information about environmental impacts. For example, stickers on new cars in the

United States rate the vehicle’s smog emissions, on a scale from one to ten. Ecolabels are placed

on products that meet certain certification standards. One example is the U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency’s Energy Star program, which certifies products that are highly energy

efficient. The Forest Stewardship Council, headquartered in Germany, certifies wood products that

meet certain sustainability standards.

In addition to environmental awareness by consumers, many businesses are seeking to reduce the

environmental impacts of their production processes. Of course, some of the motivation may be to

increase profits or improve public relations, but companies are also becoming more transparent

about their environmental impacts. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is a nonprofit

organization that promotes a standardized approach to environmental impact reporting. In 2017 82

percent of the world’s 250 largest corporations used the GRI methodology, including Coca-Cola,

Walmart, Apple, UPS, and Verizon.

6. CONSUMPTION AND WELL-BEING

If the goal of economics is to enhance well-being then we need to ask whether current levels of

consumerism are compatible with wellbeing goals. If not, then what should we do about it?

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

27

6.1 Does Money Buy Happiness?

Earlier in the module, we mentioned that utility is a somewhat vague concept, one that cannot be

easily measured quantitatively. But a large volume of scientific research in the past few decades

suggests that we actually can obtain meaningful data on well-being rather simply—just by asking

people about their well-being. Data on subjective well-being (SWB) can provide insight into

social welfare levels and the factors that influence well-being.

Collecting data on SWB involves surveying individuals and asking them a question such as: “All

things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?” Respondents then

answer based on a scale from, typically, 1 (dissatisfied) to 10 (satisfied). How much credence can

we give to the answers to such questions?

Research has shown that it is possible to collect meaningful and reliable data on

subjective as well as objective well-being. Quantitative measures of [SWB] hold

the promise of delivering not just a good measure of quality of life per se, but also

a better understanding of its determinants, reaching beyond people’s income and

material conditions. Despite the persistence of many unresolved issues, these

subjective measures provide important information about quality of life.

46

One of most interesting questions that SWB research can address is the relationship between

income level and life satisfaction. Researchers have studied the relationship between income and

SWB in three main ways:

1. Within one country, are those with higher incomes happier, on average?

2. Is average happiness higher in countries with higher average incomes?

3. Over time, does average happiness increase as a country’s average income increases?

One of the most comprehensive studies addressing the first question was a 2010 paper that was

based on the results of more than 400,000 surveys conducted in the United States, which found

that higher income does tend to be associated with higher SWB, but at a decreasing rate.

47

This

finding is consistent with the concept of diminishing marginal utility; additional income does

increase utility, but each additional dollar tends to result in smaller utility gains. It is also consistent

with the idea that people evaluate themselves relative to others.

The paper went on to measure well-being in a different way, referred to as “emotional well-being,”

which asks people to describe the positive and negative emotions that they feel on a daily basis. In

this case, higher income was associated with more positive, and fewer negative, emotions, again

at a decreasing rate, but only up to a point. At an income level of around $75,000, further increases

in income did not improve emotional well-being. The authors conclude that “high income buys

life satisfaction but not happiness, and that low income is associated both with low life evaluation

and low emotional well-being.”

46

Stiglitz et al., 2009, p. 16.

47

Kahneman and Deaton, 2010.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

28

Other studies have produced similar results. A positive, but declining, relationship between income

and well-being was also found in a 2013 study that analyzed the 25 most populous countries.

48

For

all 25 countries there was no evidence that people reach a satiation point beyond which average

SWB levels off with further increases in income.

49

The finding that income gains eventually fail

to increase emotional well-being was also found in a 2016 paper, though the income at which

emotional well-being leveled off differed.

50

The study concluded that the prevalence of negative

emotions declined steadily up to an income of $80,000, continued to decline but at a lower rate up

to an income of $200,000, and then did not decrease further with higher incomes.

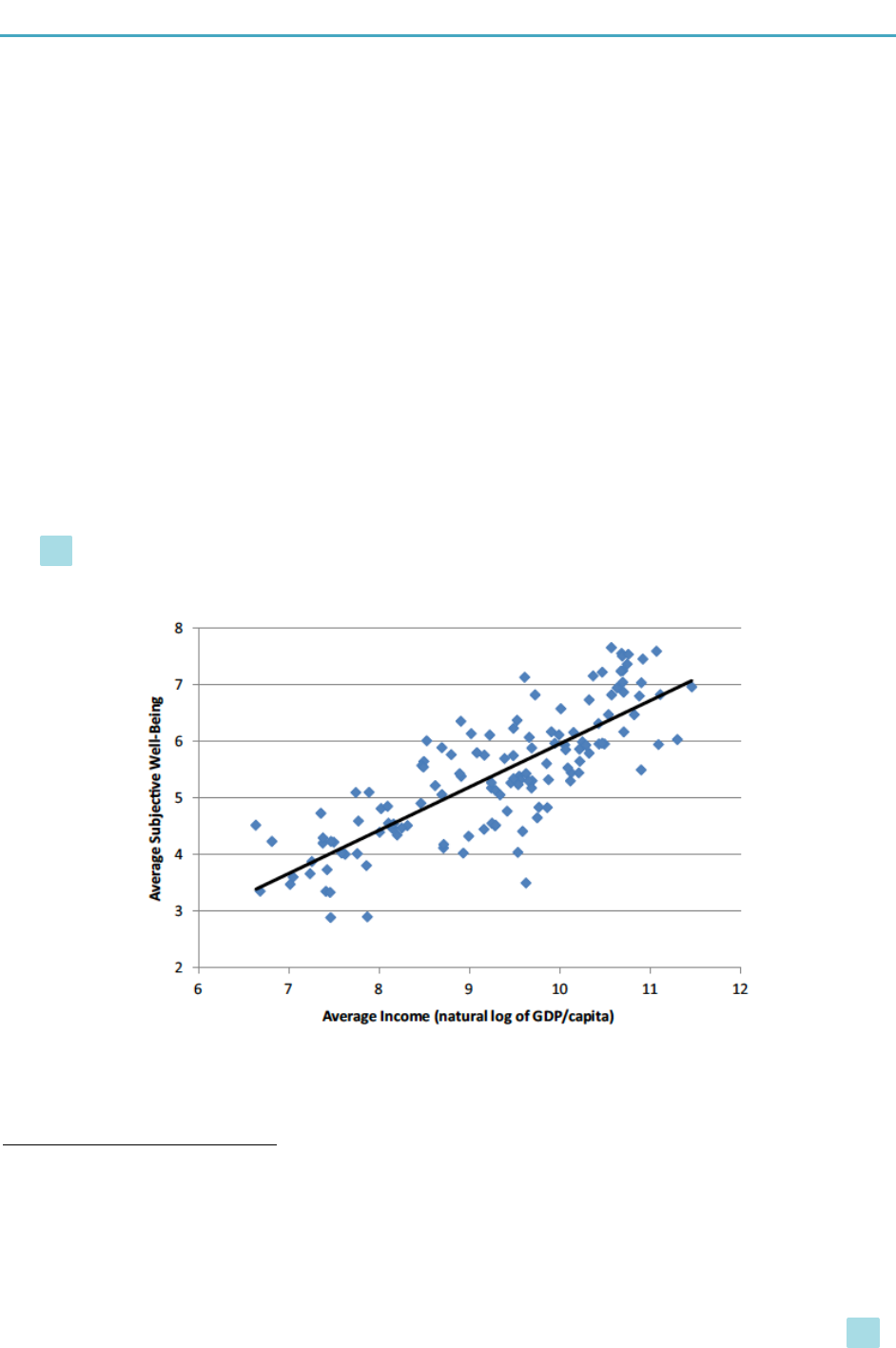

The evidence also indicates that richer countries do tend to be happier than poorer countries.

51

Again, the relationship seems to support the concept of diminishing marginal utility. So each dollar

of additional income doesn’t increase SWB by the same amount; instead each percentage increase

in income tends to increase SWB by about the same amount. We can see this is Figure 8, which

plots average incomes along the x-axis on a natural log scale.

52

Each dot represents the average

SWB and average income of one country, with data from 2016 for 133 countries. The black line

plots the overall trend, showing that countries with higher incomes do tend to have higher average

SWB.

Figure 8. The Relationship Between Average Income and Average Subjective Well-

Being Across Countries, 2016

Source: Helliwell et al., 2017.

48

Stevenson and Wolfers, 2013.

49

The results of Stevenson and Wolfers (2013) were verified by Lien et al., 2017.

50

Clingingsmith, 2016.

51

Stevenson and Wolfers, 2013.

52

A natural log scale uses the number “e” (2.718281) as its base. Thus 8 on a natural log scale represents e8, or 2,981.

A 10 on a natural log scale would be 22,026.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

29

Finally, we consider whether the average SWB in a country increases as it becomes richer. Early

studies on this topic found that average SWB stays relatively constant as a country becomes richer,

suggesting that people continue to evaluate themselves relative to others, even as they become

richer in an absolute sense. However, most of these studies looked at the United States, which

seems to be an exception rather than the rule. The most recent research finds that countries do tend

to become happier as average incomes increase.

53

One reason this may not have happened in the

United States is that higher income inequality means that the income gains that have occurred have

not been widely shared.

Overall, the evidence is rather convincing that higher income is associated with higher well-being.

However, note that this doesn’t necessarily imply that higher consumption leads to higher well-

being, although of course it is true that those with higher incomes tend to consume more. Further,

we can’t conclude that a consumerist lifestyle necessarily leads to high well-being. Other research

has explored how people’s values and goals affect their well-being. Psychologist Tim Kasser and

his colleagues have studied the mental and physical consequences of holding materialistic values.

They have used surveys to determine how strongly oriented different people are toward financial

and material goals, by asking whether it is important that, for example, they “be financially

successful,” “have a lot of expensive possessions,” and “keep up with fashions in hair and

clothing.” Respondents were also asked about their SWB, as well as questions about how often

they experience negative mental and physical symptoms such as depression, anxiety, headaches,

and stomachaches. Based on results for both college students and older adults, their results were

clear:

[Those] who focused on money, image, and fame reported less self-actualization

and vitality, and more depression than those less concerned with these values. What

is more, they also reported experiences of physical symptoms… This was really

one of the first indicators, to us, of the pervasive negative correlates of materialistic

values—not only is people’s psychological well-being worse when they focus on

money, but so is their physical health.

54

Additional research by Kasser and others finds that people who hold materialistic values tend to

be less happy with their family and friends, have less fun, are more likely to abuse drugs and

alcohol, and to display antisocial symptoms such as paranoia and narcissism. Two recent papers

55

reviewing the literature on the relationship between materialism and well-being both conclude that

the majority of studies find a negative relationship between the two. For example, a 2016 article

concludes that “materialistic tendencies can have a detrimental effect on well-being” and that

“people persistently…pursue materialistic goals rather than pursue goals that may be more

beneficial for their well-being.”

56

So in summary, while a higher income tends to be associated

with greater well-being, an excessive focus on money, status, and material possessions tends to

lower well-being.

53

Sacks et al., 2010.

54

Kasser, 2002.

55

Ditmar et al., 2014; Kaur and Kaur, 2016.

56

Kaur and Kaur, 2016, p. 45.

CONSUMPTION AND THE CONSUMER SOCIETY

30

For some individuals, consumerism itself can be addictive. According to a 2006 paper, about 6

percent of Americans are considered compulsive shoppers.

57

This is similar to the percentage of

Americans considered alcoholics. People are classified as compulsive shoppers based on their

answers to questions about whether they went on shopping binges, bought things without realizing

why, had financial problems as a result of their spending, or frequently bought things to improve

their mood. Compulsive shoppers were just as likely to be men as women, but they tended to be

younger than average and have a lower income than the average. Compulsive shoppers are more

likely to experience depression and anxiety, suffer from eating disorders, and have financial

problems.

6.2 Affluenza and Voluntary Simplicity

Economists have traditionally assumed that more income and more goods are always better,

holding all else constant. But we can never hold all else constant. One of the main lessons of

economics is that we should always weigh the marginal benefits of something against its marginal

costs. In the case of consumerism, these costs include less time for leisure, friends, and family,

greater environmental impacts, and negative psychological and physical effects. In short, there can

be such a thing as too much consumption—when the marginal benefits of additional consumption

are exceeded by the associated marginal costs.

As we have seen, people tend to evaluate themselves relative to other people. The situation of

rising consumption levels has been compared to a theater in which one row of people stands up in

order to see the show better. Then, the row behind them has to stand up, just in order to see as well

as before. The same with the row behind them, and so on. Eventually, everyone is uncomfortable

standing up, and no one is really seeing any better. Everyone would be better off just sitting down.

Economist Robert Frank discussed this problem in his 1999 book Luxury Fever.

58

He suggests that

the lavish spending of the superrich, whose incomes have increased dramatically in recent decades,